Mormon Classics | Spalding Library | Bookshelf | Newspapers | History Vault

|

Walter Scott (1796-1861) A Reply, to... Iniquitous Letters (Pittsburgh, 1824) |

|

"Rigdon Revealed, 1821-23" | Campbell's first reply (1824) | Campbell's recollections of 1823

Baxter's Life of Walter Scott | Greatrake's 1824 pamphlets | Campbell's 1825 pamphlet

|

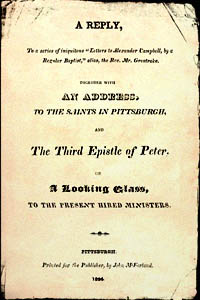

A REPLY, To a series of iniquitous "Letters to Alexander Campbell, by a Regular Baptist,"alias, the Rev. Mr. Greatrake. TOGETHER WITH AN ADDRESS, TO THE SAINTS IN PITTSBURGH. AND The Third Epistle of Peter, OR A Looking Glass, TO THE PRESENT HIRED MINISTERS. PITTSBURGH. Printed for the Publisher, by John McFarland. 1824. |

|

A REPLY, &c. Mr. Greatrake. SIR -- Allow me, to address you, as the author of "Letters to Alexander Campbell, by a regular Baptist." Allow me, Sir, through this medium, also, to inform the public, that Mr. Campbell has called upon you, relative to those letters. At your first interview with Mr. Campbell, you refused to hold any intercourse with him, as author of those letters. This point being settled, Mr. Campbell declared his errands; he told you he had seen your letters, & that he has read them; he told you that they certainly contained matter of very extraordinary complexion; in short, that they contained a number of misrepresentations, and that he was now present for your explanation. He observed, that in those letters, you had charged him with hostility to the Paedobaptists, but without any grounds whatever, as a number of documents which he had long ago laid before the publick, and which you doubtless had overlooked, sufficiently demonstrated that hostilities commenced on their side. He next told you that the enormous profits with which you had charged him in those letters, as arising from the publication of his two debates with Mr. Walker and Mr. Maccalla, far exceeded the truth, as written instruments in his own possession would ultimately doscover. He told you also, that you had entirely misrepresented his sentiments on the doctrine of the Holy Spirit, and invited you to put your finger on a single expression, in his writings, that could afford even the color of proof for such an extraordinary assumption. He suggested to you the propriety of correcting and retracting these things publicly, but you demurred; he expressed his sorrow, and was silent. Mr. Church was present. You did not know him ( 4 ) When he told his name, you were surprised, you had never seen him. He then gave you to understand that he had seen your letters. That he had read them. That he was the person who was lately baptized. THat you had alluded to him in your letters. That you had made a number of misstatements, in short, that you had openly abused him, and he was now present for your explanation. He then opened your pamphlet, and charegd it with twelve misrepresentations. He told you that they were making false impressions on the public mind; that they might do him harm, and ought to be corrected. This you admitted, with a number of these misstatements, on the spot, and tendered him your promise of immediate redress. Now, Sir, that the above and similar charges marshalled against you, in a spirit of mild behaviour, and by men too, who were entire strangers to you, should for some moments afflict you with the most terrible mental retribution, is not, I think, to be deemed very marvellous in the economy of human confusion. And could you, Mr. greatrake, think it indecorous in me, silently to direct your eye to the grey hairs of that saint, whom you had ignorantly abused? As for Mr. Campbell, that gentleman bears no other character in your letters, than that of a demon. Nay Sir, in your second you actually associate him with the idea of "Satan fondling over (as you say) his hell hounds." Mr. Greatrake, are you not ashamed of such comparisons? If this is the spirit of a Preacher, (Nolo Espiscopare,) I'll never be a Preacher. Mr. Campbell, in the whole of this interview, looked so much unlike the Devil, to whom you had been pleased to compare him -- his mild address -- in short, who whole deportment, formed such a remarkable contrast with your written description, that it could not escape even your own observation. Did he revile you, as you did him? Did he threaten? Did not conviction, Mr. Greatrake, sting you to the inmost recess of your heart? To me the interview was distressing. Your distraction could not be concealed. I was penetrated with it. I told you so, but you were become the victim of your own indiscretion. You had ruined yourself by attacking men of whose character and sentiments you were entirely ignorant -- and my commiseration was of no avail. Mr. Greatrake, I am now to make some strictures upon your letters. I am to inspect the configuration of at least four of them. But lest any should think that I meddle in other men's matters, I must tell you Sir, that I also have grievous objections to those letters and to yourself likewise. Lest any person should say that I interfere with you and Mr. Campbell, I would ask whether you Sir, have not interfered with the Church of the living God? Whether you have not slandered the Saints of the Most High? and spouted ( 5 ) forth a flood of falsehood after the followers of the Lamb? Have you not, contrary to all truth and even to probability, published that some of the Church of Christ, meeting in the Court House of this city, say that they "have been regenerated, and some say there is no regeneration, that some of them admit and some of them deny the Spirit[']s influence, while others aver that the word is the Spirit, and the Spirit is the word, and no matter whether there be any Spirit or No! That meditation, social and family prayer, are for the most part esteemed a matetr of foolishness with them." I ask, Sir, whether you have not reported these things in your letters? And would you have me silent under such scandalous aspersions? Would you have me, a mute spectator of your mean efforts to vilify the Church of God, in which I am a oastor? I must now inspect four of your letters, I say, because, you have attacked my brethren most violently in your fourth letter, and because there you have foisted us in so curiously, as to make it impossible fully to expose your conjectures without first overhauling your book from the beginning. This course may appear tedious, but we cannot help it. You have imposed the burden upon us, and we must bear it. But, Sit, I have no quarrel with your person or with your character. I am alike ignorant of both. To your own master you stand or fall. I have carefully distinguished between men and things. I have carefully discriminated between you and what you write. It is with the latter only that I have to do. It will not therefor be necessary to beplaster you with vulger epithets. -- Such things only prove ill breeding of him that uses them. As for your entire Pamphlet, Sir, whether it is to be viewed as a wanton and cruel attack upon the Church of God, assembling in the name of their Redeemer, to worship according to the commandment. Whether it is to be received as an effervescence of that priestly and malignant spirit, which has in all ages of the world opposed itself to the best interests of mankind? Whether it is to be considered as a written dosplay of your own personal hostility to Christs religion, when ixhibited in its original simplicity, and to men whose righteous efforts, in the acuse of truth, have thwarted your ecclesiastical designs in this city? Or whether your letters are to be considered in all these points toegther, it requires no great causuist, I presume, Mr. Greatrake, to determine. You then are the cause of my appearing in public, and you see my design. But think not Mr. Greatrake, that I have overlooked your design. I think I understand the proposition before you in those letters. I think I have followed you from the premises to the demonstration. I think Sir, I perceive what your object is. Nay, I am sure you ( 6 ) have taken great pains in the beginning, middle and end of your book, to let your professed design be explicitly known. I call it your professed design, because I think it differs from your real design. For who, in reading those letters, does not perceive that your object was not to become the honest biographer of A. Campbell? -- was not to exhibit that gentleman's character, but to destroy it? And there is something still more marvellous in those letters, that you have actually overshot the mark in both of these aims. You have done neither of them. Perhaps you have only made him a character, as other men make him a mantle. For if you intended to pourtray A. Campbell, as you say you did, believe me, Sir, there is such a ghostly dissimilarity between the painting and the original, as makes all the world stare, and many call aloud for the painter, who has wisely walked off in the dark. Mr. Greatrake, you are ignorant of the religious community for which those letters are designed. On the cover of your book you tell us so. Still you might have hoped, that some in those western districts, both could and would distinguish between proof and proposition, and who, when they read a book, are generally careful to sieze the authors design -- very careful to keep the writers object in view, as knowing that otherwise they might have but a dim perception of much of what he says. But let us for a moment, pay all attention to your professed design in those letters, and let yourself be our interpreter. Your first letter is prefactory, and when you come to explain it, you say, letter second, that in it you had given us to understand that the subject to be handled was Mr. Mr. Campbell's character, &c. In your third letter you say, "In the further pursuit of his (Mr. Campbell's) character, &c." And lastly, in your concluding letter you say, "I have had the best motives in endeavoring to pourtray Mr. Campbell's character." The object of those letters, then, or, logically, the proposition of your book, is an "exhibit of Mr. Campbell's character," and so it is unnecessary to multiply quotations. -- But now, Sir, to the demonstration. What is your plan? How do you demonstrate the proposition before you? How do you afford us an exhibition of Mr. Campbell's character? You are to proceed, you say, by "fact and conjecture." This is announced in your first letter, and when you come to conclude, you have these words, "I have had the best motives in endeavoring to pourtray Mr. Campbell's character from the fairest grounds of conjecture, and from the face of his doings." Here in the end of your book you profess to have employed fact and conjecture in the pourtraying of ( 7 ) Mr. Campbell's character. This plan you elsewhere define to be conformable to the gospel, and natural. You say philosophers and Christians (Divines) have both admitted it, &c. &c. You see then Mr. Greatrake. that in those interpretations of your object, and the means by which you are to attain it, you yourself have been my guide. So that when I say Mr. Campbell's character is the proposition of your book, and that fact and conjecture are the means by which you develope that gentleman's character, I only say what you have written. And now, Sir, having got into your little city and laid its gates on our shoulders, we mad march to the mountains. Very little exertion, indeed, is necessary to bring us hither. Already we seem to be there; the clamour excited by your pamphlet is fast dying away and already we seem seated as it were upon an eminence, with plenty of leisure to contemplate the unusual excitement and its ephemeral cause. But, Sir, permit me to make a short and grave essay on three words of very frequent occurence in your letters, viz: -- Chararcter, fact and conjecture. You profess to give us an exhibit of Mr. Campbell's character, and attempting to do so, you have been graciously pleased to involve the character of others also. Now, Sir, did it ever occur to you before, or after, or even, while writing those letters, that a man's character is a very sacred thing. Did it ever occur to you, Sir, that you had chosen one of the most delicate of subjects? We ought, Sir, to approach the character of one another with the greatest reverance. No display of industry or talent, how successful soever, will atone for the want of character in America. In a republic, indeed, character, I may aver, is all that a man wants. It is not so in the country from which you came; but even there, Sir, it has long ago been discovered that he who steals my purse, steals comparatively trash; but he that robs me of my good name, &c. makes me poor indeed. We ought therefore, Sir, to approach the character of one another only through the medium of well attested fact. But secondly, to your term fact, this word signifies an action, incident, or occurrence. Now of it so happens that we wish to appear in public as a witness against a fellow-citizen, we should ever let our appearance at such a tribunal and such a crisis be sanctified by fact; well established fact: remembering at the same time, that no accusation, however plausible, can live immortally, that is not thus established; besides, it is not the part of the witness to comment on his own testimony. This is the province of the public, who, in such matters are always the judges; but take for an instance, of dispassionate testimony or witness bearing, the blessed Evangils -- there all is fact -- there the entire narratives relative to ( 8 ) the Holy Saviour are mere concatsnations of fact which must live and speak to eternity. Nevertheless they are delivered without note or comment. No conhecture is admitted there, even when the probibility of the ground seemed most inviting. But now, Sir, to your term conjecture. You are to proceed partly by conjecture. Know then that our dictionary writers define a conjecture to be a guess, and a conjecturer, says Mr. Walker, is a guesser. The term in every instance implies the possibility of being wrong. Have Philosophers and Christians admitted conjecture as a legitimate source of development in the history of the equivocal character? Philosophers are false guides, too frequently, believe me, and the christians whom you mean, for I see you point to the Divines, are far less to be imitated in their manner of handling human character. But you shall judge for yourself, how nice a thing is it to manage conjecture aright? You shall see from your own book, how much, both of delicacy and judgment is necessary to be a good conjecturer. You conjecture for instance, that Mr. Campbell is hostile to the Paedobaptists, and from this conjecture, you again conjecture that he is vain, noisy and avarcious; and I say you conjecture it because you assert ot without proof, as we shall afterwards see. You conjectured also, that that gentleman printed 6,500 copies of debate, and was legitimately entitled to the profits of them all. This was a very wild conjecture, as Mr. Campbell will doubtless discover. Again, you guessed that he denied the influence of the Holy Spirit. And again, you erred, as I heard him invite you to put your finger on a single expression in any of his writings, which afforded you the least for such a conjecture, and you could not. Again, you conjectured two little stories concerning my co-pastor. They are attended with no proof. You never witnessed the scenes they describe, and no body could tell you them. You conjecture, also, that Mr. Church has joined our society; here you are wrong again. That he holds the delusive doctrine that Baptism is salvation; he has already convinced you that you erred here. You conjecture that this delusion, may perhaps, only be dissipated in hell. This is a bold conjecture, and a false one too, if he does not hold that delusion. And of the church in the Court House you conjecture, for nobody could tell you, and you never came to hear and enquire for yourself, that it holds wrong views of Baptism, scouts at the law, the doctrines of the Holy Spririt, experience and prayer and all these conjectures, are both arrogant and false! as you may learn by coming to the Court House. You say you are ignorant of the community for which ( 9 ) your letters are designed; of course you had to conjecture what would suit our taste. Well, Sir, you have provided a rich repast for such as prefer sound to sense, and declamation to fact. And, now Sir, I doubt not, you are ready to agree with me, that much both of delicacy and judgment, is necessary to make a man a good guesser or conjecturer. Having premised so much in general, we may now come to your first letter in particular. You say, it contains the subject to be handled. In your interpretation of this epistle, you say, that, in it, you had given Mr. Campbell to understand, that you were to attempt an exhibit of his character. It likewise mentions the plan or principles on which you are to proceed in the development of his character; and this is all that is necessary to be said on your first letter. Let us therefore proceed to your second. Here you fall upon Mr. Campbell and declare him hostile to the Paedobaptists; from this supposed hostility you proceed in your conjecture, and deduce his vanity; from his vanity is next conjectured the true origin of what, you call, his unceasing declamation; from his declamation, you obtain his prospects of gain; so that, almost in the same breath, A. Campbell, by the aid of conjecture, is presented to the reader, by his honest biographer, as a hostile, vain and clamorous knave. But why did you not proceed a little further in the induction, and from his prospects of gain collect his certain riches; then, Sir, with equal propriety and some show of scripture, you could have by another conjecture determined his future destiny; that is, you might have lodged him safely with the rich man in hell. But if you were going to reason from Mr. Campbell's hostility to his vanity, noise and knavery, why did you not prove him to be hostile to the Paedobaptists? Suppose your readers deny that he is hostile to the Paedobaptists, is there any thing in your book to prove it? Not a syllable; in your book it is entirely an assumption, so that the whole train of your conjecture is founded on what logicians call a Petitio principii, i. e. You take for granted the very thing in question, and you take for granted the very thing to be proved. But by whom was hostilities commenced? Do not documents, long ago laid before the public, demonstrate that the Paedobaptists were the aggressors? Did not Mr. Walker challenge all Baptist Ministers? And is Mr. Campbell to be accounted hostile because, at the solicitation of his brethren in the Ministry, he accepted the challenge? Have not two Paedobaptists assailed Mr. Campbell, viva voce? and two of them with ink and pen? And yet you assume that he is hostile to them, but utter not a syllable of their triplacate hostility to him; know you not, Sir, that "the wisdom ( 10 ) which cometh from above is without partiality?" Every fool (says the wise man) is first in his own cause, but when his neighbor comes he searcheth him out. But let it be a drawn game between you and me, let us say that they are hostile to one another; and then we may proceed to your conjecture. From this supposed fact you guess that Mr. Campbell is either a vain or a revengeful man; charity, you say, forbids you to conclude upon the last of these terms and therefore your charity makes choice of the first; but had your charity been of that kind, which Paul tells us, thinketh no evil, you, no doubt, would have found more difficulty in tracing either a scriptural or a philosophical connection between his vanity and his hostility to the Paedobaptist scheme. Nevertheless you work your way with the perspicacity of a lynx through a whole host of conjecvtures and come out quite clear, that Mr. Campbell is hostile to the Paedobaptists, ergo, he is a vain man. Mr. Greatrake, it is a poor rule that will not work two ways. Now, don't you think, Sir, that I should reason just as fairly if from your extreme complaisance towards those Paedobaptists, I should demonstrate that you are a very humble man? Yet, I am very far from thinking you such. Here it can only be said, then, that you may be out in your conjecture about Mr. Campbell's vanity. You are fond of proverbs I perceive; the Italians then say, ogni medaglio ho ilsua reverso, i. e. every medal has its two sides. And so, I say, has your proposition, but it is my turn to work with your rule of fact and conjecture; you say Mr. Campbell hates the divines of an opposite order, ergo, he is a vain man. Now, Sir, is there any love lost between them? I say the divines of the opposite order hate Mr. Campell, ergo, they also are vain men; again Mr. Greatrake, hates Mr. Campbell, ergo, he too is a vain man; now push it one step further and then because you hate one another, ergo, you are all vain men. But, Sir, if you had a spark of chairty, would you not have attempted to get off your brother Campbell on the grounds of the latin saying, odium theologicum, it is all the "hatred of divines." However if Mr. Campbell has contended with two of the Paedobaptists, is it, Mr. Greatrake, a conjecture to say, that two of them must have contended with him? And if from this you infer that he is vain are we not equally to be excused, if from the same cause we infer that -- they are vain likewise. I say, then Sir, that, in this letter you have not proved Mr. Campbell to be a vain man, by any rule, that will not equally prove all who oppose him to be vain men. But as we have granted you your unproven facr, that he is hostile to the Paedobaptists, so we shall grant you your uncertain conjecture, that Mr. Campbell is a vain man; and now, to a definition of the term vanity. Mr. Blair, in his lectures ( 11 ) on eloquence, says, that pride makes us admire ourselves, vanity makes us wish for the admiration of others. Now who admires Mr. Campbell? Do the Paedobaptists? Surely no! Does Mr. Greatrake? Surely no! But who is Mr. Greatrake? Why, if we believe himself, he is the mouth of 10,000 Regular Baptists! So then I ask again, who admires Mr. Campbell? It seems to me, he is vain to no purpose, for Baptists and Paedobaptists alike hate him; unfortunate puer; unhappy shepherd. But perhaps Mr. Greatrake, you think there is more in your second letter, than merely that Mr. Campbell is hostile, vain. clamorous, and avaricious; perhaps you think that there is more in the letter, than one supposed fact and three enthusiastic conjectures; indeed, Sir, there is nothing more. Believe me my dear Mr. Greatrake it is exceeding bald. -- Strip it of the following ragged expressions, and what will be left to secure it from shame, "vituperance, declamation, personal pique, nothing but rail, vanity insatiate, breast stirred to revenge, storm of indignation, unceasing attack, impelling principle, assault, and a good day an appetite, obloquy, Timor, Ghengis Khan, the Roman emperor, Proteus, Ishmael, Macedon, Bucephalus, &c. &c." Strip it, I say, of those low, vulgar expressions, and then you must see with myself, Mr. Greatrke, that it contains nothing more than the supposed fact, that Mr. Campbell is hostile to the Paedobaptists; and three uncertain conjectures that he is vain, noisy and avarcious. But now I am come to your third letter the beginning of which exactly corresponds to what I have said. Having noticed Mr. Campbell's hostility to the Paedobaptists, you say, and intimated the probable causes thereof, &c. in the further pursuit of his character, I will exhibit some of the impressions, &c. &c. I am glad, then, Sir, to have the sanction of your own interpretation to what I have already declared and shown to be the spirit and soul of your first epistle. I may now proceed in safety with my remarks upon your third letter; and here, Sir, I shall again allow you to be your own expositor. You tell us that, in this letter, you are to exhibit Mr. Campbell's character. The proposition of this letter therefore, is, by your own interpretation, the same with that of the former; but here it is to be remarked, you change your modus operandi, you change your plan of developement and no longer proceed by fact and conjecture, but endeavor to make us acquainted with Mr. Campbell through the medium of impressions which his writings and preachings, say you, have made upon the religious and irreligious part of the community. Now, Sir, this is reasoning precisely as I would do, were I to attempt to deduce the blessed Saviour's character from the impressions which his doctrines have made upon ( 12 ) yourself. You have read of the Nicolaitaens in the revelations; of the Adamites who assembled naked; of the Munster Baptists who practiced polygamy, and of many others who all pretended to be inspired by sentiments taught by the Saviour, and would you, Mr. Greatrake, attempt to derive a single feature of the Blessed Saviour's character from the enthusiasm of such misguided creatures? Surely no! Now this is your declared plan in this letter; through just such a medium do you propose to hold up Mr. Campbell. -- This plan, however, is of no use where the sentiments making the impressions on the community can be proved to be taught by the character in question; if sentiments are bad, they will doubtless make bad impressions, and the man whose they are, is certainly accountable for both. You speak then of Mr. C's followers, whether real or pretended, as holding "horrible sentiments," i. e. wrong views of Baptism, they scout at the Moral Law, the Doctrine of the Spirit, experience and prayer, and these, you say, exceed the whole sum of blasphemies you ever met in the character of men and devils. Now, if you intended that the plan of reasoning which you have chosen should be of any use to you; doubtless you would have been careful to identify those blasphemies the writings and preachings of A. Campbell according to your promise in the beginning of this singular Epistle. But no! On the contrary, after having enumerated a lengthy chain of horrible sentiments you say, almosr in the same breath -- let us leave "those horrible sentiments as they cannot be identified with any of Mr. Campbell's own opinions, speculations or teachings," these are your very words: Now, if none of those horrible sentiments could be identified with any of Mr. Campbell's own opinions, speculations or teachings, why, in the name of wonder, do you say any thing about them? Here you have quite abandoned your own plan; or rather you have never attempted to follow it, perhaps you did not understand it -- perhaps you did not need it -- I think you did not need it -- listen to the following sentence and tell me Mr. Greatrake, where were your condour and your wit, when you wrote it? You say to Mr. Campbell, "whether Sir, you be, or be not the teacher of such sentiments, it is of little consequence as long as they have the authority of your name," i. e. as long as his enemies attribute them to him. Now Sir, after such a memorable sentence, I am more surprised at your laying out any plan of developing Mr. Campbell's character, than at your departing from it; plan is of no use, where we are determined to have a man in the fault, whether he be or be not guilty. What, Sir, do you think it of no consequence whether the church meeting in the Court-House, do or do not hold foolish and contradictory sentiments as long as they are ( 13 ) attributed to us by yourself, our enemy? We think it of very considerable consequence, to shew that in this matter you have wither egregiously erred, or done something worse. It must also be of much consequence then in the proper development of A. Campbell's character to show whether these sentiments be or be not his; but if you wished only to make him a character and to put it on him as others would a mantle, then I agree with your renowned saying "that it is of little consequence whether he be or be not the teacher of such sentiments as long as they have the authority of his name, i. e. as long as you say they have the authority of his name! Mr. Greatrake, I ask you whether as a professed minister of Christ, you are not ashamed to speak so iniquitously in public? You have in this whole matter, Sir, laid yourself naked to attack on every side, but it is not my business to wound, but to heal, to revenge but to return good for evil, blessing for cursing. If these were not A. Campbell's sentiments, why all this noise? Why so much sound and no sense? Why such a mighty proposition and no argument? Why so much smoke and not a spark of fire? Did you want to put out your readers eyes? Did you wish to betray is into a bog? or do you think Mr. Greatrake, that if it had been your intention to exhibit and not destroy Mr. Campbell's character, that you would have used so much wind as blows, in this letter? But he that attempts to reason without argument must necessarily wriggle and nestle and speak as impertonently as he who attempts to do so without a proposition; so do you, after hobbling and puffing to the middle of your letter, at last lay your finger upon the same string and play the same tune you handled with such address in your first letter, viz: Mr. Campbell's hostility to the ministers. Again you conjecture from this old fashioned fact which, you say, is as tangible as the leaves of his Christian Baptist, that he loves fame, or in the words of your former letter, he is "vain;" besides this he is "impudent" and "ignorant" and "mad as the Knight of La Mancha or the Phrenzied Swede!" Nay, he is an "intermeddler," an "empirick" with "a chaotic mass of Will-o'-the-wisp theology," say you; the very antitype of the "Jews who murdered Christ;" yet a "Babylonian" who plagues the Spiritual Israel. In the first part, for it divides itself into two parts, there is a proposition and a plan proposed but without a thread of argument; in the other declamation and foul words are substituted for both; and it is to be pitied and borne with, because here you are fighting for yourself; you have something at stake here, and we would expect to hear of heavy blows. Skin for skin, says Satan, all that a man has, will he give for his life. -- ( 14 ) Mr. Campbell has touched your sore, and in your letters you let us know that you are not a Job. A. Campbell might have been a Socinian, Arian, or any thing, and then we could have borne with him, but when he would bereave us of the Loaves and Fishes -- Ah! there it is, even the meek Mr. Greatrake could scold here. What, Sir, did you think that Mr. Campbell would ultimately arraign you for the little heir with which you tax your mutum pecus? No, Sir, you would ever have passed unmolested -- you would ever have passed unnoticed in the tickness of that obscurity to which you have been consigned. I think, however, that you may yet be immortal. I think Mr. Campbell may yet touch you with his pen and then you will live. But, Sir, why here tell us of Mr. Campbell's hostility to the ministers and of what he "intimates and asserts of their dishonesty and selfishness?" According to your own declaration you were to treat of his character, through the medium of "impressions which his writings and preachings had made upon the public;" but how do you do it? Why even this; with the formality of a profound reasoner, for one would suppose that you really intended to reason, you remind your reader of the proposition of the letter; then you tell him how you are to proceed by "impressions made upon the mind of the community," and then you do not mention a single impression made upon the community. Next, you enumerate a series of horrible sentiments and then tell us they are not A. Campbell's sentiments. Then you get on the hobby of his hostility and this awakes your own hostility until the whole composition is become fervent with glowing expressions, such a "hell hounds," "Miltons Satan," "incestuous grand children," "Knights of La Mancha," "The Phrenzied Swede," "Jews who murdered Christ," "a Babylonian," "the poisonous Upas," &c. You seem to me to have chosen for your maxim, the very reverse of the famous Latin verse, suaviter in modo et fartiter in re, i. e. soft words and hard arguments; your words are the hardest in the English language, your arguments are so soft that they cannot be felt. Is vulgarity wit? Is conviction the result of senseless declamation? If we must convince we must argue, if we would be witty we must be wise. -- What edge does it give to your account of Mr. Church, to call him "an unregenerated man," a "speckled disciple," "a vain man," "a deluded man," "an Ignis fatuus," "a Jack-o'-the-Lantern," &c. &c. You talk of "the reproach of the wicked, the contempt of the wise, and the pity of the good." Think you not, Sir, that your own mouth is become a fit model of imitation, for the first of tehse characters and that while the scripture maxim holds, you never can be associated with either of the two; out of ( 15 ) the abundance of the heart (saith the Lord) the mouth speaketh. -- Besides, Sir, you should know that it is no proof of the badness of a cause, that it is reproached by the wicked; the Saviour's religion has ever been treated so by them and you have reproached us grievously be we his disciples or not. But I am now come to your fourth letter, and I am glad of it. I have long sailed on a loud sounding sea and still I have no bottom. I am at a great loss! Not sir, where to steer, but where to stop; not where I should begin; but where I am to end; pity me reader! for sure here is a letter as full of filth and falsehood as the sea's full of water. You set out by saying that you had noticed "some of the moral impressions." Now, stop sir; let me ask what impressions did you notice? Unless by impressions you mean the "horrible sentiments" before mentioned, but these you say can be identified with neither Mr. C's. own opinions, speculation nor teachings; yet you stupidly say "impressions made!" Now on whom were they made pray? Indeed sir, believe me that the only personage in this letter that is shown to be impressed with any thing that can be called Mr. C's., is yourself. Yes sir, Mr. C's. writings and teachings, impress no individual mentioned in this letter but yourself. And the only impression that is made, even upon you, seems to be the temerity of his doings. You are fully impressed, I perceive, with the impossibility of his attempts in his writings and teachings, and no doubt sir, you think this impression of yours an admirable proof, that his attempts will ultimately prove abortive! O quale caput. The next sentence introduces the Church of Christ in this city -- the "same fraternity" who hold the "horrible sentiments," so often alluded to; but it is not enough for Mr. Greatrake to say, that they hold wrong views of baptism, scout at the doctrine of the Spirit, the Law, experience and prayers; but he must proceed, says he, to raise up "other characteristics["] of the "same fraternity." Sir you have exhibited a strange contempt for truth. You proceed as follows -- "In this church there are two pastors." Why did you not name us out? Why did you not say in the church meeting in the court house?" Were you afraid of the law? Did you hope to deprive us of all certain means of redress? I called upon you for explanation, but you dare not, at least would not tender me any. All the city, however, know whom you mean by this church and their elders or pastors, I therefore, in this matter, sir, without ceremony speak what others think and know to be the fact, that you mean the church meeting in the court-house ( 16 ) and its pastors. You go on and say that "one of their pastors occupies an entire Sabbath in explaining a part of Scripture to his flock." Now sir, this is false and refutes itself. If one of the pastors occupies an entire Sabbath, what is the other doing? The many who attend the church, know that you have stumbled on the very threshold, and it only serves to demonstrate your consummate ignorance of our order in the court-house. Are you not ashamed sir, to be so superlatively ignorant of a thing, which you might have known by coming down to the middle of the city. No individual in the Church of Christ sir, is allowed to monpolize an entire Sabbath, that church assembles on the first day of the week "to break bread," not to listen to a pensioned preacher, besides sir, you should know from the Scripture that the flock of God, is not a mutum pecus, is not a dumb herd, like that which you tend, but being "filled with wisdom, are able to admonish one another even as they do." You next say that this same pastor surprises the whole flock with his eloquence; and when he has done they rise up to tell their neighbors and he comes to tell me. Now sir, where does he come to, in order to tell me? When he speaks in the court-house am I sitting some where else; or close by his side; and if I am close by his side as all the world knows I am! what necessity is there either for coming or going to tell me? But sir, I pronounce this story, this little story a vile falsehood. In all its parts it is the offspring of your own rash heart or who catered it for you? But sir, I forbear. As for myself I have in connection with my own subsistence, labored pretty assiduously in both sacred and natural learning for the good of my fellow citizens and their offsprings. Yes I have been five years in Pittsburgh, and now mark me Mr. Greatrake, give me five cents sir, and you are at liberty to rake my character fore and aft; and when you have fished all possible fact concerning me, sit down, give loose to your wildest airs of conjecture and then pipe them forth with all your lungs; pipe them forth to the four winds of Heaven? And we are all sure that if you had had any worse to say of my co-pastor you would have said it, all the world can see that. Your little story, sir, is a little monster defiled in all its limbs; it seems to me if I have any skill in arithmetic, to possess no fewer than seventeen members, of course that number of falsehoods stands against its father. Priests are fond of cursing, cursing things in all their parts; look, Sir, upon this rickety brat of your own, and say whether it does not deserve all the hard terms which you with so little reserve have bestowed upon others. And now, sir, you attempt to give variety to your subject by exhibiting your ( 17 ) pastor at greater length on the "margin of the river." This poor story is a very cluster of musrepresentations and the particulars are so numerous and stick so close to each others embraces, that I am scarce sharp sighted enough to pick them out and count them. What shall I say then of those misrepresentations? Why just this, that when taken all together they make one thumper. -- After stringing up a concatenation of obnoxious sentiments, you put them into your pastor's mouth and then end with this loud sounding stentence and a "hundred things of the same sort and a thousand others, and different sayings as irrelevant to the Gospel," is spoken to the raftsmen at their avocation; and what say the raftsmen? Why that the pastor is a "noble fellow," an "Antinomian," Antispiritist, Antichrist or Socinian; then they salute him with "my brother" until these jarring things make such a thumping on your own imagination, for it is all in your own brain, that you actually think yourself (as you say,) present with the devil, "groping his way through chaos and old night." Suppose Mr. Greatrake our situations were reversed and that you had to refute such stuff as the above, can you tell me how you would proceed? I am at a great loss. The excellent Mr. G. Campbell of Aberdeen, has this noble sentence, "Mere declamation, I know no way of refuting but by analizing it." And now sir, we are ready to hear you describe your pastor at social worship, I call him your pastor sir, because we recognize no such a queer character existing among us as you have exhibited. Here comes one of the drunkenest like scenes that ever graced a Bagnio. "See him, say you, recumbent upon some three or four chairs, with a cigar in his mouth disposing of its smoke with one respiration, and going on by breaks with a lecture on some part of the divine truth, or standing up at the fire mingling the fumes of his tobacco pipe with the breath of prayer and praise, issuing from the mouths of his professed brethren while engaged in their devotions! But here say you we shall stop." Yes stop Mr. Greatrake, what a pity you had ever moved a step in such vile misrepresentations! You never witnessed such a scene; and who is your authority for this little story? But if you had to stop in the middle of your story on account of its grossness, what must the reader think when he is told that he has the Rev. Mr. Greatrake for its father? Every person of understanding will easily perceive that such things are not the result of inquiry or of sound reason but of spleen; and with respect to Mr. Rigdon, believe me Mr. Greatrake, that he now lives among men of as delicate a sense of propriety and of optics as quick in the preception of good and evil, as those of many of your European sages; moreover sir, ( 18 ) I still think you are indebted to the grace of God in Mr. Rigdon. I was yesterday told by a gentleman, a gentleman sir, of elegant manners and as good nerve as any in the city, that when one of your privileged order publicly insulted him, he just as publicly knocked him down. Now I am no patron of knocking down, yet we are all inclined naturally to knock each down; and believe me sir, in this matter you owe a good deal to Mr. Rigdon's christianity. But you say you are ignorant of us as the community for which your letters are designed? You might have been silent here, nemo se accusare debet, no one is obliged to accuse himself, but I assure you sir, that some of our citizens would have horsewhipped you had you talked so vulgarly of them. I am now come to Mr. Church's case, and a very extraordinary one it is. Here you must allow me to make a remark, which may be of some use to yourself, and to the reader. It is this "that in our disputations, we are very apt to mistake men for things." Yourself for instance can entertain no grudge at the person of Mr. Church, and others alluded to, in your letters, but only at the religious course which they advocate; instead, however, of refuting this from scripture, which is what you ought to have done, you have bedaubed us all with vulgar epithets. Now these epithets can prove nothing except the ill breeding of him of him that uses them. I ask you again, sir, what good it could do yourself or your cause to bedaub every person whom you touch, with such bad names. -- Why do you call Mr. Church a speckled disciple, a Jacko'the-Lantern, an Ignis fatuus, &c.? If Mr. Church had acted wickedly, you should have proved it, and even this which you have never attempted, you ought to have done in a spirit of meekness, if you wished to go by the directions of the Holy Spirit. You did not know Mr. Church, you had never seen him, you were not present at his baptism: no wonder then that every word of your accounr of this matter should contradict all that we saw with our own eyes. You set out, in your account, by saying that Mr. Church promised to join our society; now, sir, he never promised to join our society, neither has he joined our society, he is not a member in our church. Mr. Greatrake, I am quite confounded at your apparent rashness in this publication: Mr. Church, like ourselves, sir, has a host of religious enemies, quite near him, that hate him as heartily as you can do, besides they know him much better; believe me, then sir, that if they could have brought any thing bad against him, they would have done so long ago, and I think that you, as a stranger, might have been silent. In the end ( 19 ) of your first letter, you bid Mr. Campbell attribute certain things to the Caecoethis Scribendi, i. e. to your "rage for writing;" well, sir, this is one way of getting you off, and for my own part, I am agreed; but then. I have a host of other things to bring against you. You say that Mr. Church has borne the name and made the profession of almost every sect in christendom, but Mr. Church authorises me to say that you have framed a misrepresentation, just almost as large as christendom. You have put down the names of seven of those sects and Mr. Church has never made the profession of a single one of those sects! BUt if he had, Mr. Greatrake must have congratulated him on his happy escape from them all, as he himself is to be found in none of them. Who told you that Mr. Church bargained with us to discourse on baptism? If he did, he was a truce breaker, for sure he did not harangue us on baptism; but on a quite different subject, as all the world knows, viz: -- on the constitution of Christ's church and on that of the Presbyterian church. You say he spoke five hours, here sir, you are out by one hour and three-fourths, you say he recited what Mr. Campbell had wrote on Baptism; he did not speak ten minutes on this institution, and, in that time, he only read a few scriptures. You say that he has professed and reprofessed; this, also, is a mistake; but, sir, I am tired out with enumerating errors, and as Mr. Church is to subjoin a letter to this; I only remark that if you had made so many blunders, falsehoods, and misrepresentations, about a matter which occurred in your own city, and which you might have seen or might have received all proper information on, who will believe you in what you say of the character of Mr. Campbell who lives 40 miles distant from you, and whom you never saw but once about ten minutes. I shall put you in mind of a solemn promise which you made to Mr. Church to correct these misrepresentations and others, which I have passed over; yes, Mr. Greatrake, you promised first, in the presence of Mr. Campbell and myself, to correct these misrepresentations, and you failed. You renewed your engagements in the presence of Mr. Rigdon and myself' but have you fulfilled your renewed promise? You have not! Now, could any thing cancel this obligation? Could any thing relieve you from the solemnity of your promise, unless you had discovered that all you had said about Mr. Church was actually true? In a letter to Mr. Church you assign as a reason for this truce breaking that Mr. Church had afterwards bestowed some illiberal epithets upon you, at least report said so. Could this relieve you from the duty of correcting what you know is undoubtedly false? I think not! -- besides, sir, you should remember the worldly maxim, ab alio ( 20 ) expectes alteri quod feceris. You have bestowed many hard epithets on Mr. Church who takes the present opportubity of tendering you the following letter. MR. CHURCH'S LETTER TO MR. GREATRAKE. MR. GREATRAKE, You oblige me to appear in public under very peculiar circumstances. It seems odd that I should have to defend myself against the attacks of an enemy I dont know, and yet it is not less odd, that I should be attacked by an enemy that does not know me. -- This however, we must attribute to the times in which we live, they are certainly perilous in the extreme. You are the author of "Letters to A. Campbell, by a regular Baptist;" and in those letters you have taken the liberty to speak of my baptism and of myself also. Well sir, there is nothing in such a liberty incompatible either with the institution or with my character; and had you spoken an a warrantable mannerof either, I never could have taken it amiss. But Mr. Greatrake there are certain things in your letters relative to my baprism and to myself which do not correspond to fact; and it was in respect to those things, sir, that I took the liberty to call at your house in company with Mr. Campbell and Mr. Scott. I deem it unnecessary here to enumerate these things specifically; it will be sufficient to say that in my interview with you, I told you they amounted to twelve. These, you will remember, I pointed out to yourself in the presence and hearing of the above named gentlemen. I told you they were misrepresentations; that they were making false impressions on the public mind; that they might do me harm; that they could do you no good, and consequently, they ought to be corrected. All this you acknowledged and professed yourself ready to make a prompt, and an adequate redress, or to remind you of this in the terms of your own letter, you said "I will with pleasure avail myself of the earliest opportunity to correct any such mistake and remove the consequenr impressions from the mind of the public." You asked me "if this would satisfy ( 21 ) me," I replied, "it would entirely satisfy me." I left your house and returned to my own in patient expectation of the appearance of your notice in the Recorder, which by the way it was agreed upon, should be the medium through which your corrections should be brought before the public. I was disappointed, your notice did not appear. The misrepresentations were still before the public; they continued to make false impressions; I knew they might do me harm; that they could do you no good; and I was aware they ought to be corrected. I returned to your house in company with Mr. Rigdon and Mr. Scott. I informed you of my errand. I told you I had been disappointed, and requested an explanation. -- You asigned a reason with which I was satisfied; and renewed your promise in the presence of the above named gentlemen to be ready with your paper of corrections against a proper day. The day arrived; again I was disappointed; no communication from you appeared in the Recorder; but on the contrary you wrote a letter to me informing me that you had heard some floating rumors about exceptionable language and illiberal epithets bestowed on you by me. This was a marvellous reason Mr. Greatrake, why you should demur -- why you should violate your solemn and renewed promise to correct what you admitted and even now know to be false; nevertheless, it was manifest from tidings brought you by your friend that I had used exceptionable language and illiberal epithets, and this you conceived was a reason weighty enough to "cancel all obligations on your part to take any public notice of my injury." And did it cancel all obligation on your part to fulfil your promise, your solemn promise made before witnesses? Have you not committed a multitude of mistakes? Have you not admitted these mistakes before witnesses? Did you not allow that they ought to be corrected? Did you not promise they should be corrected? You did, and in the presence of heaven and earth I charge you with the violation of your promise. I have subjoined your letter in which the promise and the violation of it are both recognizable. ( 22 ) MR. GREATRAKE'S LETTER TO MR. CHURCH. MR. CHURCH, SEN. ( 23 ) which perhaps you are indebted in a measure to others, lest in resenting a supposed injury you commit a real one, and for which it will not be so easy for you to make reparation. My house is as yet, open to your visits, but to no triumvirate. Well, sir, it is true, I came to your house "upon the presumption (if presumption it may be called) that I was alluded to" in your letters -- but did you not do away all presumption? Did you not by acknowledgement, and by the truce which you made with me to correct certain misrepresentations, as stated in the above letters, convert my presumption into reality? But certainly, sir, such an epistle as the above makes but little ibservation necessary. You would have me return to your house alone to make a new bargain. But what security, pray, do you offer, that more regard will be paid to [your] second than to your first engagement? Having been bold enough to violate your first promise, made in the [presence] of witnesses, there remain no grounds to believe that you would fulfil a second, amde [not in] the presence of witnesses; for your house is not open to a triumveriate, i. e. to myself and witnesses. Have you not violated your solemn truce or covenant made with me in the presence of Messrs. Campbell and Scott, on the 24th August, viz: -- that you would publicly correct the falsehoods in your letter? You have, sir, -- you renewed this promise on the evening of the 24th, before Messrs. Scott and Rigdon; but have you fulfilled even your renewed promise? You have not, sir. On the contrary, I received the above letter on the 3d of the month, without date, and with your fictitious name to it; you, as the assassin, like to plot in the dark? Did the Saviour act so? No, sir! The Lord Jesus was all openness, and commanded his disciples to proclaim on the house top, whatever they heard in secret. But, sir, I cannot vlose this letter without putting one question, and you must not think me officious in doing so: You must not think, that I meddle with other men's affairs, when I do so, for I apprehend that every person who reads Mr. Campbell's writings ( 24 ) is concerned in the question. Why have you wickedly and maliciously published that Alexander Campbell denies the influence of the Holy Spirit? This scandalous assumption or rather falsehood is the very foundation of your low, clamorous address to the Baptists, and you assert it boldly, for instance you say Sal of Tarsus "denied Jesus of Nazareth," you, (Mr. Campbell,) deny the Holy Spirit from Heaven. Now, sir, read the following passages from that gentleman's writings, which were in your hands at the moment you wrote your invention, No. 12, page 191. "I know of no passage in the New Testament" says Mr. Campbell, "that says that the spirit of God accompanies any of our preachers words; besides, the disciples are the sons of God and have the spirit of Christ." Now, Sir, Mr. Campbell declares it not as his opinion but as a scriptural fact that the disciples, i. e. all disciples, have the Spirit of Christ; but though Mr. Campbell believeth that the Spirit of God, i. e. the Holy Spirit is no accompanier of those men called preacher's words: What does he say of the Holy Spirit and Gods words? Why as follows. "The age of miracles and gifts has passed away and now the influence of the Holy Spirit is only felt in and by the word, i. e. (of God, the New Testament,) believed" No. 8, page 184, and are you not ashamed, Mr. Greatrake, to say with this in your hand, that Mr. Campbell denies the influence of the Holy Spirit? But, sir, are you so ignorant as not to know that all the gifts of the Holy Spirit admit of a threefold division -- that the Holy Spirit blesses men either with power, wisdom, or goodness. In the primitive ages he blessed the disciples with miraculous power and with extraordinary wisdom to understand mysteries; all these miraculous gifts have ceased, and now the fruits of the Spirit "is in all goodness," in them that believe the word of God. This, sir, is certainly no false doctrine! But Mr. Campbell has inserted a letter in his 9th No., on this very subject, and has declared that same letter to be worthy of the examination of his readers; now this number was in your possession at least four months ago, so that you had not a spark of grounds to assert that he denied the influence of the Holy Spirit, and extract this lie from your address to the Baptists and, what becomes of it. This falsehood, sir, is the very body, soul and spirit of that dirty piece. But we have now two essays on the work of the Holy Spirit, from the pen of Mr. Campbell himself; and what does he say? Why that we owe every thing in and about our religion to the Holy Spirit, that this Holy one not only established the truth but may be said to have ( 25 ) "made the truth" in the 9th No. it is said by the author of that piece, that his "saving influence in the production of faith and repentance, and of every other gracious effect by which we are made partakers of a divine nature, is, by the word of truth, put into the mind and written upon the heart;" and this he says, "seems to be the general opinion of, at least, all "the most eminent writers," &c.; and yet you tell the Baptists that he has attempted to rob them of the only "comforter," "the condescending Holy Ghost." Sir, I believe you wished to destroy the character of Mr. Campbell and to set aside his great usefulness; but you have missed your mark -- you have been quite premature -- your rashness has slain you -- you have fallen into your own net -- you have ensnared yourself -- your reputation is gone, and your inoquitous letters will doubtless be held in that execration which they so justly merit.

WM. CHURCH.