Greatrake Home | Rigdon Revealed | Mormon Classics | Newspapers | History Vault

Lawrence Greatrake (1793-c.1840)

Miscellaneous Historical Sources 1

Various News Items (1813-1832) | Reminiscences of Wilmington (1851)

Autobiographical Recollections (1860) | Charles Willson Peale (1947)

"Gilpins Papermaking Machine" (1957) | Early Engineering Reminiscences (1965)

"Dickinson's Paper Machine" (1967) | Rockdale... (2005) | L.G. Sources Part 2

|

Charles R. Leslie Autobiographical Recollections... (Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1860) |

|

Greatrake mentions in text below: p. 2 p. 3 p. 6 p. 8-12 p. 12-13

|

News Items (from various papers) 06-27-1813 06-04-1817 07-25-1817 08-14-1822 08-19-1822 08-23-1822 |

|

|

No. 448. Wilmington, Saturday, June 20, 1813. Vol. V. COMMUNICATION. FOR THE WATCHMAN. _____

|

|

No. 450. Wilmington, Saturday, June 27, 1813. Vol. V. FOR THE WATCHMAN. Mr. Wilson. -- I observe in your paper of the 20th inst. an address signed Lawrence Greatrake, evidently intended to prosuce a belief that he has been the innocent victim of unmerited oppression upon the part of the Marshal of this district, in having been sent into the interior, as an alien enemy. A regard to the dictates of truth, which have been egregriously violated in almost every line of this production, induces me to submit a brief explanation of the causes which led to that measure. |

|

Vol. IX. Wilmington, Del., Wednesday, June 4, 1817. No. 707. DIED, at Brandywine Paper Mill, near Wilmington, on the 14th inst. of a short but severe illness, occasioned by an attack of the Gout in the Stomach -- LAWRENCE GREATRAKE. a native of Bristol, England; residence in this country seventeen years. He has left a wife and eight children to mourn his loss. -- |

|

NS. Vol. I. Wilmington, Del., Wednesday, July 25, 1817. No. 2. ALL PERSONS having any demands upon the estate of Lawrence Greatrake, of the Brandywine Paper Mill, lately deceased, are requested to produce their accounts for settlement, and those indebted to the same, are respectfully requested to make payment to George Greatrake, who is authorized to receive it. THOMAS GILPIN, Ex. |

|

Vol. XIII. Baltimore, Md., Friday, May 14, 1819. No. 113.

|

|

Vol. II. Georgetown, D.C., Friday, June 23, 1820. No. 2215.

|

|

Vol. XVII. Baltimore, Md., Wednesday, April 18, 1821. No. 2552.

|

|

Vol. XVIII. Baltimore, Md., Thursday, Aug. 23, 1821. No. 44.

|

|

THE WILMINGTON GAZETTE. Vol. ? Wilmington, Del., February 26, 1822. No. ? There has been much damage done in the neighborhood of this place by the freshet. The chain bridge at Brandywine was carried away, and with it the corner of a flour mill. The water was from twelve to eighteen inches deep on the lower floors of the other mills, and some injury was sustained in consequence of the wetting of grain and flour. The dams are all swept away. Several persons were standing on the bridge at the time it gave way and were carried down the current; two men are missing. The machinery in the cotton mills has been injured by being wet. The sulphur mill of Mr. Du Pont was carried away. A stone building belonging to Messrs. J. &. T. Gilpin's paper establishment, and used for the purpose of preparing rags, and one thousand dollars worth of paper, entirely finished, accompanied them. Several small buildings were destroyed, and some other injury done to other parts of their establishment -- their loss is estimated at fifty thousand dollars. The water is stated to be two feet higher than it was ever known before in the Brandywine. The whole loss by the flood is estimated at one hundred thousand dollars. |

|

Vol. XX. Baltimore, Md., Thursday, Aug. 8, 1822. No. 30.

|

|

Vol. XX. Baltimore, Md., Monday, Aug. 12, 1822. No. 33.

|

|

Vol. XX. Baltimore, Md., Wednesday, Aug. 14, 1822. No. 35.

|

|

Vol. XX. Baltimore, Md., Monday, Aug. 19, 1822. No. 39.

|

|

Vol. XX. Baltimore, Md., Friday, Aug. 23, 1822. No. 43.

|

GENERAL ADVERTISER. Vol. ? Philadelphia, Fri., April 30, 1824. No. 11,950. NOTICE OF SALE. WEREAS the President and Directors of the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal Company, in conformity with the powers in them vested, have heretofore made and signed orders for the payment at certain times and in certain proportions of the monies payable by the proprietots of stock... Now therefore notice is hereby given, that said President and Directors will on the first day of June 1824, at 7 o'clock in the evening, at the Merchants Coffee House in the city of Philadelphia, sell at auction and convey to the purchasers the sahre of the said proprietors so refusing or negelecting payment... H. D. Gilpin, Sec'ry. James C. Fisher, President.... |

|

Vol. ? Philadelphia, Penn., Thursday, April 5, 1832. No. ?

DIED, on the 9th day of March, 1832, at. St. Mary's, Georgia, of a pulmonary affection, George Greatrake, of the Brandywine Paper Mills, in the 38th year of his age. In the impressive remembrance of the conduct and merit of the deceased, a tribute seems to be alike due to the feelings of the living, and the character of the dead. In the several relations of the filial and social duties, he was led to support an even tenor of conduct, and to perform the part alloted him with affection, perseverance, and fidelity. |

|

H. B. Hancock and

N. B. Wilkinson "The Gilpins... Machine" PMHB Vol. LXXXI No. 4 (Philadelphia: P.H.S., Oct., 1957) © 1957 Penn. Historical Society All rights reserved. Fair use excerpts only, reproduced here. |

|

(pages 393-395 not transcribed, due to copyright restrictions)

|

Anthony F. C. Wallace Rockdale... (Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 2005) © 2005 Univ. of Nebraska Press All rights reserved. Fair use excerpts only, reproduced here. |

|

|

George Escol Sellers Early Engineering Reminiscences (Washington, DC: Smithsonian, 1965) |

|

Entire contents © 1965 by the Smithsonian Institution, all rights reserved.

Only limited, "fair use" excerpts are reproduced here.

|

[ 96 ]

In 1817 or 1818 [sic - 1817], George Escol Sellers, not yet ten years old, journeyed with his father to see Thomas Gilpin's new cylinder paper machine on the banks of Brandywine Creek, just north of Wilmington, Delaware. The area was a center of industry that included mills for the manufacture of paper, flour, gunpowder, cotton goods, and textile machinery The paper mill of Thomas Gilpin had been established 20 years earlier by his elder brother Joshua Gilpin and Miers Fisher. Flour mills had been in operation since before 1750, and by the 1780's several were employing Oliver Evans's bucket-and screw-conveyors. The powder mills were those of E.I. du Pont de Nemours, who had opened them in 1802. William Young's cotton factory and the machine shops of the Hodgson brothers have been mentioned in chapter 9. It was in the Hodgson machine shops on the Brandywine that George Escol's uncle, Franklin Peale, had learned the machinist's trade. Thomas Gilpin's paper machine, patented in 1816, was based upon the similar machine of John Dickinson, of London, patented in 1809. Details of Dickinson's machine had been obtained through the extensive European travels of Joshua Gilpin and from Lawrence Greatrake, who had returned to England on personal business at the time the Gilpins were considering the practicality of producing machine-made paper in America. Other cylinder paper machines machines followed Gilpin's, as related by Sellers. Of John Ames's patent for a cylinder machine, the editor of the Journal of the Franklin Institute commented in 1833 that he could detect nothing novel in the Ames specification, since Ames was merely adapting a design that had originated in France and that had since been improved in England and in the United States.

[ 97 ]

I have no distinct recollection of my father's visit to the mill at that time. But I do remember that he and Mr. Gilpin and his manager, Mr. Greatrake, spent much time in the machine room watching the operation, sketching and discussing points in connection with the forming cylinder and the exhaust pumps. The millwright had been... __________ [Editor's notes] Lawrence Greatrake is known to me only through these pages and a series of his letters in the Gilpin papers in Historical Society of Pennsylvania (kindly pointed out to me by Norman B. Wilkinson). Bound in a volume entitled "Paper Making Machinery -- 1816 -- Property of Richard Gilpin" there are several of Greatrake's letters to Thomas Gilpin between September 1815 and April 1816. The date of Greatrake's first coming to the United States is uncertain. He mentioned, however, that "had I staid another year in England, I had been a partner in the immense concern at Apsley."... Greatrake's letters indicate that he could not obtain a cylinder to take to the Gilpins, as he had hoped to do.... In 1815 Franklin Peale married Eliza Greatrake, daughter of Lawrence. The marriage was a tragic one, for within a year or two Eliza became hopelessly insane. Dickinson purchased the Apsley mill in 1809 (Anon., "The Firm of John Dickinson and Company Limited," London, 1896. p. 7). about the time his paper machine patent was issued. Thus Greatrake may well have been Dickinson's right-hand man, as related by Sellers; but his letters do not suggest an earlier familiarity with the development of the Dickinson machine.

[ 98 ]

I also visited the cotton factory of my father's old friend, Mr. William Young, who had, in connection with his factory, a good machine shop for that period. It was in this shop that my uncle, Franklin Peale, served his apprenticeship We spent the evening with Mr. Gilpin in his bachelor quarters, Messrs. Du Pont and Greatrake being of the party. The making of paper by machinery in all its aspects was discussed, also the feasibility of drying the paper by steam heated cylinders.... |

|

B. G. Watson “John Dickinson and His Paper Machine” The Paper Maker 36:1 (Wilmington, DE: Hercules, 1967) |

|

Entire contents © 1967 by the Hercules Powder Co., all rights reserved.

Only limited, "fair use" excerpts are reproduced here.

|

[ 31-35 ]

A number of articles have appeared in earlier issues of THE PAPER MAKER which have discussed, in detail, the work of Joshua and Thomas Gilpin... Joshua, the elder brother, during his visits to Europe between 1795 and 1801, and again between 1811 and 1815, met many of the British paper-machine machine pioneers, including Hall... he was obviously anxious to find out all he could about new machinery, and consider whether it would be of use in their new mill. Of an excursion he made to Nash Mills, in 1796 (before it belonged to Dickinson), he mentioned that it had recently been built under the supervision of Hall, and he was particularly impressed with the salle -- "being the most extensive and perfect I have elsewhere seen." Another mill he visited in the same area is referred to as "Greatrakes Mill," It was described as "...an old patched affair with two engines and vats." Without doubt this was Apsley Mill, which had been owned by the Greatrake family for some years. In 1792 James Greatrake was in correspondence with James Whatman, and four years later Roger Greatrake was the papermaker at the mill. Gilpin mentions Lawrence Greatrake in his journal, and it was this member of the family who was eventually to work in America, assisting the Gilpins in the development of their paper machine. As we have seen, Dickinson had bought Apsley Mill from Staddord in 1809, and it would appear that at this time Lawrence Greatrake was employed at the mill. He is also spoken of as having been foreman at Nash Mills, and it may well be that in the years before he left England he worked in both the Dickinson mills. He wrote a letter about Dickinson as "the genius, the gentleman, and the liberal mind" and on another occasion as a "Young Man of Science, very Gentlemanly in his manners, and... of great Mechani[ca]l talents." Nothwithstanding his esteem for his employer, Greatrake was persuaded by the Gilpins to work in their mill. It is not certain when he first went to America, but it was probably about 1808 [sic - departed in 1799]. By this time Dickinson's mould-machine was working, though not commercially, and Greatrake would have been familiar with its construction. Since the English patents were not effective in America, there is little doubt that by employing Greatrake, the Gilpins hoped to build and run a copy of the machine. In a recently published book, it is reported that George Escol Sellers wrote of a visit to Dickinson in the summer of 1832: "Mr Dickinson asked me if I had ever met a Mr. Greatrake in America, who many years before had been taken from him by Mr. Thomas Gilpin offering a higher salary than he could at the time afford to pay. Notes: (forthcoming) |

|

Charles C. Sellers Charles Willson Peale (NYC: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1947) |

|

Entire contents © 1947 Charles Scribner's Sons, all rights reserved.

Only limited, "fair use" excerpts are reproduced here.

|

[ 286 ]

... If Titian [Peale] said that he could not learn dead languages, his father asked the school to excuse him from those classes, and so it went. Constraint was a last and dreadful recourse. Instead, he would offer only encouragement and advice, emphasizing, too, that innocent pleasures are a necessity of life. His children, after the manner of children, responded with a love that was not tempered by respect, and very rarely expressed in obedience.... After completing his year at Hodgsons', Franklin went, in December, 1814, for another twelve months' service at William Young's cotton factory outside of Wilmington -- their machine cards were manufactured at Coleman Sellers' wire works, which gave him the entrance there. Thence he returned to Belfield to open the cotton factory of his own. In the meantime, however, to the mingled distress and amusement of his family, the youth had fallen in love with a Quakeress -- not an ordinary Quaker girl, but a strange, unctuous creature, older than himself, given to awesome silences and sudden ejaculations of a religious character. Of course he must join the Society. His father sent him a copy of the Portraiture of Quakerism, wrote himself in praise of the Friends, and hoped for the best. It was a changed Franklin who now visited the farm -- the tassels off his boots and the ruffles gone from his shirt front -- his eyes warm with devotion, his lips formed to pious utterances.

[ 287 ]

Sybilla, at the same time, but in a very different vein, was writing to Lin, now absent at an army post. "Oh I only wish you could come home to see a fine job of a wedding here and some Quaker Preachers that are coming into the family. You would crack your sides laughing to know who it is. Try all your might to get a furlough, for besides the pleasure of seeing you, I would not that you should miss the pleasure of being groomsman and going into meeting with your great sword by your side and uniform on for the world.... |

|

Elizabeth Montgomery Reminiscences of Wilmington... (Philadelphia: T. K. Collins, 1851) |

|

|

38 REMINISCENCES OF WILMINGTON. to be further described, where many visitors from the neighborhood and cities have been so hospitably entertained. Mr. Gilpin resided here with his family the latter part of his life; and died there in the year 1841. In the day of prosperity, the large stone house opposite the mill was occupied by Lawrence Greatrake, who managed the concern of paper-making. Death summoned him suddenly, in the vigor of life, to leave this extensive business and his large family. A youthful son succeeded him in the management of the establishment for years. It was a beautiful spot, and all around it was kept in the neatest order, shaded by trees, shrubbery and vines. Yet no withered leaves or broken branches marred the rich verdure on this hill. The mistress of the mansion, Mrs. G., arranged all within her bounds in good taste. The court in front was adorned in beauteous order, with many flowering shrubs. The balcony in the rear overlooked the creek and mills, and far beyond; and the steep hill descending was covered with rich grass, and handsome trees well trimmed, so that the view was not obscured. On one side was the garden, with a serpentine walk the whole length of the high ground, and planted with different species of trees and shrubbery, consisting of some hundred varieties, completely shaded. Here and there was an arbor, decorated with vines and furnished with stools painted white. This presented the most picturesque view. At the entrance of the estate was a neat cottage, called a lodge, at vhich the road divided into three ways, with a large gate to each; a private one led to Kentmere, a lower one to the mill below; and the centre one to this house and the mills above. There are many who gratefully remember the civilities tendered to them by this family, especially those caught in rains or thunder-storms in their rambles up these banks, and sought shelter under their roof. Some far away, who have been educated at Hillis’s boarding-school, may not forget the memorable evening when the entire school fled to this mansion to VISITORS TO THE MILLS. 39 seek an asylum from a pelting rain, and the perplexity, as night approached, with no appearance of a change in the weather, and how George Greatrake exhibited his kindness in ordering the large covered mill wagon, geared with four horses,in which fifty or more girls were closely packed like reams of paper, standing erect, secure from the rain. They had a merry ride: though slow, it was sure and novel; a carriage conveyed the teachers home, and this was deemed an event in their life. The daily crowds of visitors here one would think must be wearisome to master and man, yet all were met by cheerful faces, their curiosity gratified, and questions answered, however frivolous, and the greatest civility extended in passing through the various departments. Some one was ready to show all that you desired to see. Mr. G. Greatrake, by personal exertion in the freshet of '22, impaired his constitution, and became the victim of a disease of the lungs, and in a few years died at the south, whither he went to recruit his health. From his knowledge of the business, and popularity with the workmen, his death was a great loss to the establishment. But the business being changed and the estate having fallen into other hands, everything was soon on the wane; and we lament to note the decline and fall of an establishment of which this town could once boast, as unrivaled in its order and pleasant scenery, and the delight and amusement of distant friends in their walk to view the operations at the old paper-mill. How old things have changed! The buildings are noe cotton mills with additions. The beautiful trees and tasteful ornaments are laid low in the dust. Like the elder members of this hospitable family, they are mingling with the earth.... Notes: (forthcoming) |

|

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

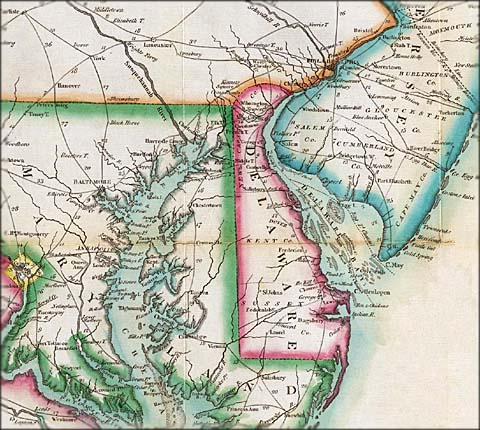

Baltimore-Philadelphia Area c. 1815 (larger image) (under construction) |

Return to top of the page

"Undercover Campbellite, 1822-25" | Greatrake's Aug. 1824 pamphlet | Campbell's reply (1824)

Walter Scott's 1824 pamphlet | Greatrake's Nov. 1824 pamphlet | Campbell's 1825 pamphlet

Greatrake's 1826 pamphlet | Greatrake's 1826 Redstone Assoc. letter | Greatrake's 1827 book

Greatrake's 1830 pamphlet | Greatrake's 1831 pamphlet | Greatrake's 1836 pamphlet

Greatrake's 1838 pamphlet | Greatrake source material 2 | Redstone Baptist Assoc. Minutes

Sidney Rigdon "Home" | Rigdon's History | Mormon Classics | Bookshelf

Newspapers | History Vault | New Spalding Library | Old Spalding Library

last revised July 17, 2008