THE COLLECTED WRITINGS OF SIDNEY RIGDON

The First Theologian of the Latter Day Saints

|

Sidney Rigdon (?)

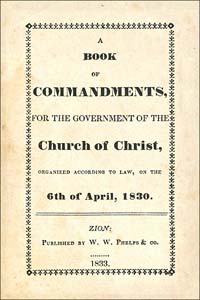

Book of Commandments (Independence, Missouri: 1833) 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 |

|

Book of Mormon (1830) | Lectures on Faith (1835) | Sidney Rigdon... Book of Mormon (2005)

|

|

18

1 A Revelation given to Oliver, in Harmony, Pennsylvania, April, 1829, when they desired to know whether John, the beloved disciple, tarried on earth.

Translated from parchment, written and hid up by himself.

|

|

31

1 A Revelation given to Joseph (K.,) in Harmony, Pennsylvania, May, 1829, informing him how he must do, to be worthy to assist in the work of the Lord.

|

|

60

1 A Commandment to the church of Christ, given in Harmony, Pennsylvania, September 4, 1830,

|

|

115

A Revelation to the bishop, and the church in Kirtland, Ohio, March, 1831.

|

|

Transcriber's Comments

(view high resolution scan of title page) The 1833 Book of Commandments From William H. Whitsitt's Biography of Sidney Rigdon: pp. 320-334

Chapter VIII.

The first book of the work in hand being now copied in the best style be could control, Harris could conceive of nothing that would be so potent to hush the complaints of his wife Lucy, as a sight of its contents. To enter his house empty-handed was to a man in his situation a truly irksome affair; he wanted something to show for himself. Accordingly he importuned young Smith most ardently for permission to carry to Palmyra for exhibition the manuscript of the Book of Lehi, which was comprised in a hundred and sixteen pages of his own character. The request was not well received; Lucy Smith says it was three several times proposed, and all but the last time refused. At length, however, Joseph yielded the point, after the exaction of a binding written obligation from Mr. Harris, which contained the injunction that none but the five members of the Harris household in New York should be admitted to view it (Joseph Smith, pp. 124-5). Though the promises that had been required of him were of the most explicit conditions and very sacred, Mr. Harris was so proud of his treasure that it was out of his power to keep them. He exhibited the manuscript first to one person and afterwards to another outside the limits of the prescribed circle. Curiosity regarding it must have been brought to a high state; it was duly gratified in every case where the person who made application "was regarded as prudent enough to keep the secret," except in the case of the Smith family, who it is complained were "not allowed to set their eyes upon it" (Joseph Smith, p. 130). The manuscript was kept by Harris under lock and key; its receptacle was a bureau which stood in the parlor, and he was in strict possession both of the key to the drawer and also of the key to the parlor door, but by some means which he was never able to explain the document was abstracted from its place while he was asleep. On his wife being asked where it might be she solemnly averred that she did not know anything about it. Diligent search was made throughout the house; beds and pillows were incontinently ripped open, and every exertion that desperation could suggest was made, but to no purpose at all (Joseph Smith, p. 131 and p. 129). The day when the loss occurred was marked by a considerable calamity to the wheat of Mr. Harris: the crop being at the moment in blossom, a dense fog spread itself over the fields and blighted it with mildew. This note of time as recorded by Lucy Smith would fix the date of the loss in the first days of July 1828, since this cereal is in blossom about that period in the latitude of Palmyra. Joseph would speedily obtain tidings of the disaster in Pennsylvania, but it is not likely that he took any steps in the affair until there was space allowed for communication with Mr. Rigdon in Ohio. Finally when Rigdon reached Harmony a council seems to have been held that resulted in a journey to Palmyra in which it is competent to suspect that he accompanied Joseph. At least this is the most natural inference to be derived from Lucy Smith's account of a mysterious stranger who was present with her son all the way in the mail coach, and when the young man alighted, though a foot journey of twenty miles through a dense forest by night was in front of him this gentleman was so deeply interested in his welfare as to break his own journey and to traverse the entire distance with a man who was completely unknown to him. Arrived at the hovel of the Smiths the kind stranger was so eager to continue his journey as to obtain his breakfast and take his leave about the dawn of day (Joseph Smith, pp. 126-7). It was apparently sometime before setting forth from Harmony on this occasion that young Smith was favored with his first revelation from the Lord. It bears date Harmony, Susquehanna county, Pennsylvania, July 1828, and foreshadows the admirable powers which he afterwards displayed in the matter of always falling on his feet (D&C, Section 3). The reason for placing this particular revelation at the head of the list may be seen in the fact that it was set down there in the early editions of the Book of Doctrine and Covenants. In the edition of Orson Pratt, Sr., it is given the third position in the order of number, but the two which come before it were both of later origin. Section 1, which was originally designated as "the Lord's Preface to this Book," was produced for a special occasion at Kirtland Ohio on the first of November 1831 (Book of Doctrine and Covenants, Fourth European edition, Liverpool 1854, p. ix), but Mr. Pratt has concealed that fact. The second revelation in Mr. Pratt's edition (Section 2), is nothing more than a passage copied from the Autobiography of Joseph Smith, which was not composed until the year 1838, when Smith was engaged in the task of reconstructing his early history upon pictorial and marvelous principles (Pearl of Great Price, p. 63). The substance of this initial revelation was with a great deal of very human shrewdness adapted to the exigencies of the disaster in which Joseph now found himself involved; announcing that the work which had come to naught in the way above indicated was not the work of the Lord, but rather the work of man; rebuking Smith for his weakness in the point that he had "gone on in the persuasions" of Harris: promising in case of more prudent circumspection that his honors should be restored, and assuring him and all that the designs of the Lord in this concern should finally triumph above every sort of opposition. It is also to be observed that his suspicions induced him to perpetrate an act of injustice against poor Martin Harris, by calling him "a wicked man" but it was not to be anticipated that a person in his present state of excitement should be wholly just towards one who had experienced a misfortune that was felt so keenly by all who were well disposed towards the enterprise. Martin was to be pitied; he did not deserve to be blamed for purfidy. It was to this unexpected casualty that the first opening of the life of the prophet is due. Hitherto it was not in the calculation that Joseph should play any other role than that of a simple translator (Omni 1:11); but the existing emergency could not in his judgment be fairly surmounted without resort to the more sure word of immediate revelation, and hence through it his future career, he was always ready to assume in addition to the original scheme, the title and the functions of a "Revelator." It would be a point of interesting speculation to inquire whether this new prophetical function was undertaken at the suggestion or with the consent of Mr. Rigdon. The demand for some such bold stroke was imperative, but in case Rigdon had any hand in helping to deliver it he was beyond dispute unwise, since he thereby placed in the way of his subaltern a ready means of rising above the principal figure in the movement. On the contrary, if the first revelation was exclusively a conceit of Joseph's it must have been already apparent to his partner that he had formed an alliance with a character who was more powerful and adroit than would in all relations be desirable, however convenient such qualities might be regarded in seasons of embarrassment or of danger.

Chapter IX.

Lucy Smith professedly employing the very words of her son, supplies the following account of this transaction: As I was pouring out my soul in supplication to God that if possible I might obtain mercy at his hands, and be forgiven of all that, I had done contrary to his will, an angel stood before me and answered saying that I had sinned in delivering the manuscript into the hands of a wicked man, and as I had ventured to become responsible for his faithfulness, I would of necessity have to suffer the consequences of his indiscretion, and I must now give up the Urim and Thummim into his (the angel's) hands. This I did as I was directed, and as I handed them to him he remarked 'If you are very humble, and penitent, it may be you will receive them again; if so it will be on the 22nd of next September' (Joseph Smith, pp.132-3). When shortly after that date young Smith's father and mother contrived to obtain passage to Pennsylvania, the "first thing which attracted her attention on entering; the house was a red morocco trunk, lying on Emma's bureau, which Joseph shortly informed her contained the Urim and Thummim and the plates." These dates and facts indeed are given from the memory of an aged person who set them down about fifteen years after the occurrences were enacted; but while there may be room enough to question their accuracy in detail, they are yet sufficient to indicate the correctness of the conclusion drawn from other sources that the manuscript of Rigdon The treasure being again restored to Joseph he preceded in a feeble way to prosecute the work before him. His wife Emma wrote for him as her domestic occasions would offer a few moments of leisure, but no great amount of progress would be accomplished this way. Joseph had now become aware of the benefit derived from the presence of a scribe, who might serve to keep him to his task, and he had received a promise from the angel of the Lord that one should be given him (Joseph Smith, p. 134). Emma Smith herself refers to the aid she bestowed upon her husband: "In writing for your father I frequently wrote day after day, often sitting at the table close by him, he sitting with his face buried in his hat, with the stone in it and dictating hour after hour with nothing between us." The above is perhaps in one or two points a fancy sketch; it was drawn at the distance of 51 years from the events, and there was ample time for the memory to become a trifle hazy. It leaves no great room to doubt however, that Smith's wife was induced to lend a hand to the business of transcription. Into this period of depression and partial idleness may with some degree of likelihood be placed the faults of dissipation which Joseph was charged with while he resided in Pennsylvania. Mr. Levi Lewis of Harmony testifies that "he saw him intoxicated at three different times while he was composing the Book of Mormon" (Howe p. 268). The winter of 1828-9 was wearing drearily away In the month of February of the latter year the father of Smith was once again enabled to pay a visit to Pennsylvania, where the old gentleman was rewarded and delighted by another revelation which conveyed to himself a call to the ministry of the gospel (D&C Sect. 4). This was the second revelation and the first call to the sacred office given in the new movement. This call was perhaps (set forth) in the words of a formula that Mr. Rigdon may have considerately provided for the use of Joseph under necessities of this kind. It was conceived in strict terms of Disciple orthodoxy, and expressly disclaims the evangelical notion of a divine call to the ministry. Their position and the hand of Rigdon are particularly apparent in the following provisions: "Therefore if ye have desire to serve God ye are called to the work, for behold the field is ripe white already to harvest, and lo, he that thrusteth in his sickle with his might, the same layeth up in store that he perish not, but bringeth salvation to his soul" (D&C 4:3-4). This idea regarding the nature of the call to the sacred office was at that time strenuously insisted upon by the theologians of Rigdon's communion, and is still maintained by them; but there was a palpable impropriety in the conduct of Smith who presented the formula in the [shape] of a divine call when the words of it themselves indicate that nothing more than a simple desire to serve God might constitute a sufficient call to the work. Most of the earlier proclaimers of Mormonism were honored with a copy of this Disciple formula. The call of Oliver Cowdery was conveyed in these terms of spotless Disciple orthodoxy: "Yea, whosoever will thrust in his sickle and reap, the same is called of God" (D&C, 6:4). The call of Hyrum Smith is given in the very same words (D&C, 11:4), as also that of Joseph Knight, Sr. (D&C, 12:4), and of David Whitmer (D&C, 14:4). The general principle of procedure in such cases is thus summed up in another place, "And if they desire to take upon them my name with full purpose of heart they are called to go into all the world to preach my gospel to every creature (D&C, 18:23). The wound which had been inflicted upon poor Martin Harris hurt him sorely throughout the summer and winter of the year 1828; it was clear to his mind that to neglect the opportunity for a speculation in the precious metals like that afforded by the "Golden Bible" would be an act of pecuniary madness. Hence in the month of March 1829, about a month after the visit of Joseph Smith, Sr., he sets out once more to inspect the condition of affairs at Harmony, Pennsylvania. The influence of his wife Lucy Harris however, was now beginning to be apparent in the attitude which Martin was assuming towards the project. Mrs. Harris could have no objections to investing her money in the way her husband suggested, provided that Smith would give a plain and indisputable demonstration that he had in his possession the treasure of which he so often prated. This sensible precaution of his better half did not at present seem so unreasonable in the estimation of Harris. Accordingly when he arrived at the residence of Joseph his temper of mind was almost as critical and inquiring as that of his wife had been the year before. He informed Joseph that he could not help him any further in the speculation except he should be favored with a "greater witness." This demand implied a sight of the "plates," and permission to handle and to inspect them until he might be convinced that they were just (what he claimed them to be). Of course it was impossible for Joseph to accede to that condition; but in order to evade the issue he proposed to "go into the woods where the Book of Plates was, and after he came back that Harris should follow his track in the snow, and find the book and examine it for himself." The purpose of this arrangement was to cast the blame upon the Lord who could, it might be affirmed, (have) been at pains to remove the book in the interval that should elapse between the moment when young Smith retired, and that in which Mr. Harris approached the spot where it was concealed.But this skillful conceit was not satisfactory to Martin; he "followed Smith's directions and could not find the plates and was still dissatisfied" (Howe, p.261-5). In such an emergency Joseph was again constrained to have recourse to visions of the Lord; he got a revelation for Martin's especial behoof, in which the whole question was treated from the standing-point of the heavenly chancery. This revelation is marked Section 5 in the Book of Doctrine and Covenants and is dated "in Harmony, Susquehanna county, Pennsylvania, March 1, 1829." An important change of policy is announced in that communication. Mr. Harris had succeeded in convincing Joseph that it was indispensable there should be eye-witnesses of the existence and the character of the "plates," if it were expected that people should believe what he asserted. Smith offered as a pretext against this the fact that the Lord had commanded himself "to stand as witness of these things" (D.&C., 5, 2); but with as good grace as he could command he yet acceded to what was clearly a dangerous requirement. Accordingly he caused the Lord to specify as follows: "But this generation shall have my word through you, and in addition to your testimony, the testimony of three of my servants, whom I shall call and ordain, unto whom I will show these things, and they shall go forth with my words that are given through you" (D.&C., 5:10-11). This concession must have occasioned a deal of disquiet on the part of Mr. Rigdon, but his colleague had enjoyed such exceptional privileges in the art of jugglery that there was reason to anticipate that he would come through the questionable ordeal with distinction. A second demand of Mr. Harris is believed to have referred to the performance of a miracle by the hand of young Smith in order to demonstrate the truth of his claims and assertions; but Joseph was easily made to extricate himself from an embarrassment like that. His method was as follows: "And you have a gift to "translate the plates, and this is the first gift that I bestowed upon you, and I have commanded that you should pretend to no other gift, until my purpose is fulfilled in this; for I will grant you no other gift until it is finished" (D&C, 5:4). Nevertheless it was not desirable to Harris to take leave without making an effort to bind him further. To accomplish that design it was conceived to be important for Martin to be made aware that his individual doings had been mentioned in the prophecies of Nephi several centuries prior to the coming of our Savior. To bring this result about it was decided to cause him to write a few pages for the Book of Mormon, in the course of which Smith would pretend that the ancient prophet had predicted his journey to visit Prof. Anthon. Revelation enjoined that special scheme in the following terms: "And if this be the case, behold I say unto thee Joseph, when thou hast translated a few more pages thou shalt stop for a season, even until I command thee again; then thou mayest translate again" (D&C 5:30). Inasmuch as he was only a few pages in the calculation, Mr. Harris could hardly refuse to lend his aid to the young man for that amount, and there is reason to conclude that the 27th Chapter of 2nd Nephi was at this time written down by Martin at his friend's dictation. The chapter in question contains a prediction concerning the three witnesses that had just now been mentioned in the revelation for Martin's behoof, besides relation of the recent conversation held by Mr. Harris with the man of linguistic lore in the city of New York, both of which points it was conceived ought to be of advantage to wavering faith. Indeed it is difficult to understand why a character like Martin should have failed to yield on the spot to the arts of his young friend; Joseph was certainly skillful in setting his springs on this occasion. But the warnings and wisdom of his spouse would be still ringing in the ears of Mr. Harris. Contrary to the expectations of Smith he persisted in his demands regarding a sight of the "plates" and as that was entirely out of the question, Harris took up his luggage and returned to his place in New York. When after all these efforts to capture him, he yet succeeded in effecting his escape, there must have been small hope in the mind of Smith that Mr. Harris would ever stand among his followers. Almost any other person would have been lost to the cause from that instant; but Martin was a weakling both in respect to his superstitious credulity and also in respect to his passion for gain. Mr. Smith was meanwhile obliged to search elsewhere for a secretary. |

Back to top of this page.

OPENING NEW HORIZONS IN MORMON HISTORY

Sidney Rigdon 'Home' Page | Sidney Rigdon's Writings

Old Mormon Newspaper Articles Index | Smith's History Vault

Oliver's Bookshelf | Spalding Studies Library | Mormon Classics

last updated: June 21, 2011