Mormon Classics | Spalding Library | Bookshelf | Newspapers | History Vault

|

SIDNEY RIGDON AS PORTRAYED IN WORKS OF FICTION |

1843: Monsieur Violet | 1854: The Great Highway | 1855: Mormonism Unveiled

1861: Jessie, The Mormon's Daughter | 1874: The Portrait | 1887: Button's Inn

1899: The Mormon Prophet | 1935: Wives of the Prophet | 1951: Country Salt

|

Stephen W. Fullom (1818-1872) The Great Highway (London: 3rd, combined ed., 1854) |

|

|

THE G R E A T H I G H W A Y: A Story of the World's Struggles. BY S. W. FULLOM, AUTHOR OF "THE MARVELS OF SCIENCE," ETC. ETC. With Illustrations on Steel by John Leech. "There are more things in Heaven and Earth, Horatio, Than are dreamt of in our philosophy." -- Shakspeare. Third Edition. LONDON: G. ROUTLEDGE & CO. FARRINGDON STREET. NEW YORK: 18 BEEKMAN STREET. 1854. |

|

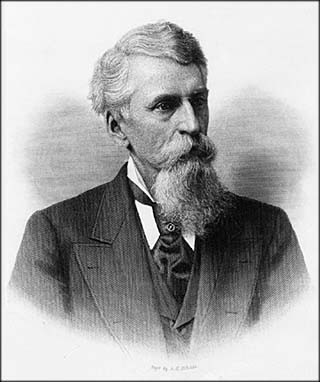

Albert G. Riddle (1816-1902) The Portrait (Cleveland: Cord & Andrews, 1874) |

|

Riddle's letter to James T. Cobb | 1887 Robertson letter

|

THE PORTRAIT A ROMANCE OF THE CUYAHOGA VALLEY BY A. G. RIDDLE AUTHOR OF "BART RIDGELEY" B O S T O N NICHOLAS & HALL CLEVELAND: CONN, ANDREWS & CO. 1874. |

|

[ iii ]

(under construction) |

|

Riddle's Letter to James T. Cobb

|

|

Albion W. Tourgee

(1838-1905) Button's Inn (Boston: Roberts Bros., 1887) |

|

|

BUTTON'S INN BY ALBION W. TOURGEE AUTHOR OF "A FOOL'S ERRAND," "HOT PLOWSHARES," ETC. BOSTON: ROBERTS BROTHERS. 1887. |

A Map of Chautauqua County, New York, as it was in 1825 (two years after Button's Inn was built)

|

[ ix ]

001 "A JOLLY PLACE IN TIMES OF OLD." 018 "A FAIR YOUNG MISTRESS." 029 A REGULAR BOARDER. 057 A VACANT CHAMBER. 091 A KNIGHT OF THE ROAD. 118 A COMMERCIAL VIEW. 140 A MODERN EPHESUS. 165 A "SENSIBLE AND TRUE AVOUCH." 177 "ASHES TO ASHES." 200 ON THE VERGE OF DESTINY. 212 THE BENISON OF PEACE. 233 AFTER MANY DAYS. 257 A MISSION OF MERCY. 265 BLOTTED OUT. 274 A SUDDEN START. x CONTENTS 287 YESTERDAY'S WOE. 305 FULFILLING LOVE'S COMMANDMENT. 315 THE SHADOW OF CRIME. 335 IN THE NEW JERUSALEM. 345 THE VOICE OF THE PROPHET. 357 UNEXPECTED RESULTS. 365 A FUTILE QUEST. 375 AWAKENED JUSTICE. 386 PARTITION AND PARTNERSHIP. 394 SAINTS AND SINNERS. 402 SOUL SCOT. 410 A WEAVER'S KNOT. 415 THE WORLD'S MUTATION. |

|

[ 018 ]

OZRO! Oz-r-o-o!" The voice was clear and full... (pages 18-28 not transcribed) |

|

[ 029 ]

EIGHTEEN years before our story opens... (pages 29-56 not transcribed) |

|

[ 057 ]

THE... (pages 57-90 not transcribed) |

|

[ 091 ]

MR DEWSTOWE was one of the most enterprising and successful of the peripatetic merchants of a generation ago. He was not only a merchant, but a horseman as well... (pages 91-117 not transcribed) |

|

[ 118 ]

DON'T you want to ride as far as the village,... (pages 118-139 not transcribed) |

|

[ 140 ]

IT was a jolly company that gathered at Button's Inn that night... (pages 140-164 not transcribed) |

|

[ 165 ]

ONLY Dewstone, the stranger from the South, and the German remained... (pages 165-176 not transcribed) |

|

[ 177 ]

IT was a busy period that intervened between the early autumn... (pages 177-199 not transcribed) |

|

[ 200 ]

A STORM had set in with the going down of the sun... (pages 200-211 not transcribed) |

|

[ 212 ]

THE morning of Christmas dawned cold... (pages 212-232 not transcribed) |

|

[ 257 ]

THE horses dragged slowly up the hill... (pages 257-264 not transcribed) |

|

[ 265 ]

MY son was dead... (pages 265-273 not transcribed) |

|

[ 274 ]

IT was with no feeling... (pages 274-286 not transcribed) |

|

[ 287 ]

I HAD been down to the harbor... (pages 287-304 not transcribed) |

|

[ 386 ]

ASKING his company to excuse him... (pages 386-393 not transcribed) |

|

[ 410 ]

SO the Christmas merry-making... (pages 410-414 not transcribed) |

|

[ 415 ]

(pages 415-418 not transcribed) |

|

Lily Dougall (1858 -1923) The Mormon Prophet... (Toronto: W. J. Gage, 1899) |

|

See also this book's entire text on-line

|

The Mormon Prophet BY LILY DOUGALL Author of The Mermaid, The Zeitgeist, The Madonna of a Day, Beggars All, Etc. T O R O N T O THE W. J. GAGE COMPANY (LIMITED) 1899 |

|

[ v ]

In studying the rise of this curious sect I have discovered that certain misconceptions concerning it are deeply rooted in the minds of many of the more earnest of the well-wishers to society. Some otherwise well-informed people hold Mormonism to be synonymous with polygamy, believe Brigham Young was its chief prophet. and are convinced that the miseries of oppressed woman and tryannies exercised over helpless subjects of both sexes are the only themes that the religion of more than two hundred thousand people can affors. When I have ventured in conversation to deny these somewhat fabulous notions, it has been earnestly suggested to me that to write on so false a religion in other than a polemic spirit would tend to the undermining of civilized life. In spite of these warnings, and although I know it to be a most dangerous commodity,

vi THE MORMON PROPHET. As, however, to many who have preconceived the case, this narrative might, in the absence of explanation, seem purely fanciful, let me briefly refer to the historical facts on which it is based. The Mormons revere but one prophet. As to his identity there can be no mistake, since many of the "revelations" were addressed to him by name -- "To Joseph Smith, Junior." He never saw Utah, and his public teachings were for the most part unexceptionable. Taking necessary liberty with incidents, I have endeavored to present Smith's character as I found it in his own writings, in the narratives of contemporary writers, and in the memories of the older inhabitants of Kirtland. In reviewing the evidence I am unable to believe that, had Smith's doctrine been conscious invention, it would have lent sufficient power to carry him through persecutions in

PREFACE. vii

viii THE MORMON PROPHET. Near Kirtland I visited a sweet-faced old lady -- not, however, of the Mormon persuasion -- who as a child had climbed on the prophet's knee. "My mother always said,"

PREFACE. ix In criticising my former stories several reviewers, some of them distinguished in letters, have done me the honour to remark that there was latent laughter in many of my scenes and conversations, but that I was unconscious of it. Be that as it may, those who enjoy unconscious absurdity will certainly find it in the utterances of the self-styled prophet of the Mormons. Probably one gleam of the sacred fire of humor would have saved him and his apostles the very unnecessary trouble of being Mormons at all. Im looking over the problems involved in such a career as Smith's, we must be struck by the necessity for able and unprehudiced research into the laws which govern apparent marvels. Notwithstanding the very natural and sometimes justifiable asperations which have been cast upon the work of the Society for Psychical Research, it does appear that the disinterested service rendered by its more

x THE MORMON PROPHET. L. D. MONTREAL, December, 1898. |

|

Sydney Bell (1907 -c.1992) Wives of the Prophet... (NYC: Macaulay Co., 1935) |

|

Copyright © 1935 Macaulay Co., Inc. - Only "fair use" limited excerpts provided here

|

WIVES OF THE PROPHET ~~~~~*~~~~~ ~~~~~~~ By Sidney Bell THE MACAULEY COMPANY, NEW YORK 1935 |

|

[ 293 ]

Early the next morning Emma went directly to Sidney Rigdon's home. Nancy met her at the door, but something in the older woman's face checked the questions that sprang to the girl's lips. "May I see your father alone for a little while, Nancy?" "Yes, certainly, Sister Emma. Go into the parlor. He's with mother now, but I'll fetch him right away." "Nancy -- I'd rather your mother didn't know I am here. Need we disturb her?" "No, no, Sister Emma. I shall arrange it," the girl assured her as she darted away. While she waited in the neat front room which served also as Apostle Rigdon's study, Emma's mind flew back over the years to another grave interview with Sidney Rigdon. Then he had sought her out on her lonely walk across a New York hillside. Then he had appealed to her to take Joe back into her heart -- to work with them all for the Power and Glory of Zion. The scene came back like a clear, vivid picture, subtle in nuances. She had been influenced that day by Brother Sidney's pleading. She had taken Joe back, had come with them, all the way, to do her part in the building of the Empire. Today the situation was curiously reversed. She was seeking out Sidney Rigdon to ask of him a great favor. Would he remember that other time? The years had made great changes in them both. Through all their vicissitudes and triumphs, there had been no recurrence of that intimacy of mind that had marked their morning talk there near the old Smith shack but a short while before Joe's flight to the West. There had been brief moments when Emma had caught glimpses of the other man -- the real man she sensed in Sidney Rigdon, a man quite unlike the nervous, fanatical preacher whose ambition for fame and glory would not yield to Joe's unscrupulous, irresponsible

[ 294 ]

Emma had ceased to wonder why Brother Rigdon remained with the Mormons. Intuition told her that knew more in his perceptive grasp of human beings and life itself than the Prophet would ever know. But wonderment at his presence in Nauvoo came back as her eyes scanned the titles of the leather-bound books on the shelves lining one side of the room, books which Sister Rigdon had brought from their Boston home -- Plato, Marcus Aurelius, a book, there in one corner, entitled The Everlasting Mercy. This last Emma had seen before and recalled it now as the Bible of a thirteenth century monk named Cyril, who claimed to have received it, engraved on copper plates, from the Angel of the Lord. How strangely like the story of their own Golden Plates this was. On the walls hung pictures of crumbling structures -- the Parthenon, the Forum, the Arch of Titus. No other Nauvoo parlor knew such pictures. Emma sensed a beauty in the permanence of these bleak ruins that vaguely corresponded with Apostle Sidney's inner self. It linked up with his austere, tender devotion to a suffering, invalid wife, with his scrupulous guardianship of his children, with his unspoken deference to her, the Prophet's wife. It was to this man, the hidden other man, to whom Emma knew she must now appeal. Casually she picked up the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius and turned the pages. Her eye caught the penciled lines along the margin of a paragraph, and she paused to read. Often think of the rapidity with which things pass by and disappear, both the things which are and the things which are produced. For substance is like a river in a continual flow, and the activities of things are in constant change, and the causes work in infinite varieties; and there is hardly anything which stands still. And consider this which is of the future in which all things disappear. How then is he not a

[ 295 ]

|

|

Howard Babcock Drake (1889-1956) Country Salt... (Philadelphia: Dorrance, 1951) |

|

More on Rigdon's post-Nauvoo life

Copyright © 1951 Dorrance & Co., Inc. - Only "fair use" limited excerpts provided here

|

COUNTRY SALT A Historical Novel BY HOWARD B. DRAKE DORRANCE & COMPANY PHILADELPHIA |

|

Transcriber's Comments

Albion Winegar Tourgée (by Margaret Toth) Albion Winegar Tourgée: soldier, carpet-bagger, judge, and novelist, was born in Williamsfleld, Ashtabula County, Ohio, in 1838. His early years were spent on his father's farm in Williamsfield, and later in Kingsville, except for a brief excursion to Lee, Massachusetts, where he lived with his uncle, Jacob Winegar. In 1859, after alternately teaching in an elementary school and attending Kingsville Academy, he was admitted to the University of Rochester as a sophomore. He left the University in January, 1861, taught for a short time in Wilson, Niagara County, New York, and in April of that year enlisted in the 27th New York Volunteers. In accordance with the common practice of awarding degrees to students who had enlisted before completing their academic work, the University granted him an A.B. degree in June 1862... (University of Rochester Library Bulletin, Spring 1953) Albion Winegar Tourgée was the son of Louisa Emma Winegar and Valentine Tourgee, who were married in Ohio in 1837. Louisa Emma Winegar was born on June 5, 1809 in Lee, Berkshire, Massachusetts; she was the daughter of Jacob Winegar (1771-1852) and Sally West. Jacob was the son of John Winegar (1743-1798) and Elizabeth Doty. One of the brothers of John Winegar was Samuel Winegar (1747-1808) whose son Samuel Thomas Winegar (1782-c.1848) joined the Mormons near Kirtland Ohio in 1833. Thus, Samuel Thomas and Jacob were first cousins and Jacob's daughter Louisa Emma was a second cousin to the Mormon children of Samuel Thomas Winegar -- one of whom was the g-g-grandfather of the current transcriber (Dale R. Broadhurst). (under construction) Lily DougallThe Mormon Prophet focuses on the life of Susannah Croome who becomes the wife of Angel Halsey, a devotee of Joseph Smith. A young and impressionable girl, Susannah is fascinated by the rumors circulating in the neighborhood about her neighbor Joseph Smith, and decides to find out more about him. Fascination quickly leads to involvement, and Susannah casts her lot with the new religious sect after meeting and falling in love with Angel Halsey. Susannah is never really converted to Mormonism, and she soon becomes disillusioned with her husband, but she remains with the Mormons for duty's sake, until the group has moved from New York State into Ohio, then to Missouri and Illinois. The Mormon Prophet is a basically accurate, somewhat biased recounting of the Mormon movement, stopping short of the final trek to Utah where the church is based today. In addition telling Susannah's story, this novel also centers upon Joseph Smith's life -- which is chiefly important to history for its psychological explanation of Smith's puzzling character. Lily Dougall was the Canadian authoress of a dozen novels and the first editor of The World Wide, a Montreal journal of contemporary though. Her works reflect a deep sensitivity to moral and religious ambiguity. Inaddition to her interesting and insightful presentation of the Mormon founder, Joseph Smith, she also attempts to explore in an even-handed manner the role of women in early Mormon society. The Canadian authoress -- attempting to report on Joseph Smith's expected public refutations of the Spalding authorship claims for the Book of Mormon -- could locate no such rebuttal and was forced to put fictional words in his mouth (see p. 320). Literary World, 4/29/1899, p. 141. N. Y. Times Book Review, 4/29/1899, p. 277. N. Y. Times Book Review, 9/23/1899, p. 636. (under construction) Stephen W. Fullom

Fullom's fictional fantasy is far from realistic when he describes the events of a Mormon dancing party, complete with tobacco, liquor, and a fiddle-playing Joseph Smith. While the writer's description of Smith is somewhat convincing, he fails totally in his effort to depict "a dark, sinister-looking" Elder Sidney Rigdon -- who, nevertheless is an approving affectionado of popular music. On pages 230-31 of the 1854 combined-volume 3rd edition, Fullom has his fictional Rigdon devising a parable from the lyrics of a dance tune, which results in an unconvincing picture of the Mormon leader. In fact, Rigdon was not even residing in Nauvoo at the time the scene supposedly takes place. Even less accurate is Fullom's description of the March, 1832 tarring and feathering of Smith and Rigdon, which he retrospectively places in a non-existant "Hiram, Jackson county," Missouri (page 234). In Fullom's imagination, the tarring and feathering incident happened "in Missouri," sometime prior to 1844, "when that Judas, Simmonds Rider" [sic - Symonds Ryder] "sold" Joseph Smith "to the mobbers, at Father Johnson's, in Jackson county." Such an account not only mistakenly transfers the location from Portage county, Ohio, to Missouri, but also makes the ex-Mormon elder, Symonds Ryder, a falsely pretending faithful member, who hands the trusting Smith and Rigdon over to their persecuting enemies. In fairness to Mr. Fullom, it should be noted that there were few published accounts of reliable Mormon history available for his consultation at the beginning of the 1850s. Few non-LDS books or articles of that period mention the 1832 tarring and feathering incident -- for example, Eber D. Howe evidently did not feel it was an event of suitable significance for inclusion in his 1834 Mormonism Unvailed. Subsequent non-LDS writers, who relied upon Howe's reporting, were generally liable to pass over the 1832 assault without mention, or with a muddled conflation of sundry 1830s Mormon "persecution" accounts. Instances of such conflation can be seen in newspaper articles published throughout the 19th century: two typical reports were published in the Utica Morning Herald of Aug. 31, 1877 and the Pines Plaines (NY) Register of Oct. 22, 1886, both of which mistakenly tie the Hiram incident with 1837-38 reaction to the Kirtland bank failure. Probably not until Stenhouse (1873), Kennedy (1888), and Bancroft (1889), were relatively accurate histories of the Hiram period in Mormon history made widely available by non-LDS writers. Fullom's incidental mention of a "Pelatiah Allen, Esquire, of Hiram," who "gave the mobbers a barrel of whiskey," helps identify the author's source material for his "Unknown Tongue" chapter.That source was almost certainly the anonymously-authored 1851 history, The Mormons, (attributed to Charles Mackay).

On pages 62-65 of that book's first edition, the 1832 tarring and feathering is related, complete with a reference to "Pelatiah Allen, Esq., who gave the mob a barrel of whiskey." The English writer of the 1851 history merely reproduced Joseph Smith's own story of the assault -- probably copying the text from the Liverpool Millennial Star, which had reprinted Smith's account from an 1844 issue of the Nauvoo Times and Seasons. Fullom adds a detail lacking in either the original Mormon text, or its 1851 British reproduction. The fictional account has Joseph Smith boasting: "That Simmonds Rider, mark ye, took sick and died." Now this is a particularly strange assertion, placed on the lips of the Mormon leader; for in 1845, a year after Smith's death, his newspaper at Nauvoo was still speaking of a very much alive Symonds Ryder: Resolved, That as a last passing notice to all our enemies and apostates, of all grades, from Simonds Rider down to John C. Bennet and Sidney Rigdon, inasmuch as their bowels and mouths are like Etna and Vesuvius, full of filth and fire consuming their vitals, that they vomit toward the northern ocean, and leave Nauvoo, to take breath and live awhile in peace. In fact, Elder Symonds Ryder lived to the ripe old age of 78, as is documented on his 1870 tombstone, at Hiram, Ohio. Elder Ryder's survival into old age may actually have been an indirect indication that he did not participate in the March 24, 1832 attack upon Smith and Rigdon. In 1846 Luke S. Johnson (a son of John Johnson, the Mormon leaders' host in 1832) visited Nauvoo and was reported as saying: "all but one who were engaged in mobbing, tarring and feathering Joseph and Sidney in the town of Hiram, Portage county, had come to some untimely end, and the survivor, Carnot Mason, had been severely afflicted" (see note 4 in Max Parlin's 1966 "Conflict at Kirtland," page 250). If, by December, 1846 "all but one who were engaged in mobbing" of 1832 had died, then Ryder's continued earthly existence seems to have argued in favor of his having not been a participant in the tarring and feathering activities. S. W. Fullom's 1854 book is readable and occasionally entertaining. It offers a slightly higher grade of mid-19th century British fiction featuring Mormons, than does its contemporary effort by Percy B. St. John, Jessie, the Mormon's Daughter. But the modern reader (particularly an historically informed one) will find the storyline hopelessly outdated and unedifying. (under construction) Albert G. Riddle

One of the novels written by A. G. Riddle, the Mantua writer, was "The Portrait." The scene of the story is mainly Mantua, but virtually all towns in Portage County enter into it. The characters, many of them, are actual Portage County people of the period. Of these are Prophet Joseph Smith, the Mormon leader, Sidney Rigdon, and others. Writer Riddle gives the following character sketch of Smith: "The Prophet was then about twenty-five years of age, and nearly six feet in height; rather loosely but powerfully built, with a perceptible stoop of his shoulders. The face was longish, not badly featured, marked with blue eyes, fair blond complexion and very light, yellowish flaxen hair. His head was not ignoble, and carried with some dignity; and, on the whole his person, air and manner would have been noticeable in a gathering of men. He was attired in neat fitting suit of blue, over which he wore the ample cloak of, blue broadcloth, which he threw back, exposing his neck and bosom -- all with a simple and natural manner." (under construction) |

Return to top of the page

Sidney Rigdon "Home" | Rigdon's History | Mormon Classics | Bookshelf

Newspapers | History Vault | New Spalding Library | Old Spalding Library

last revised June 9, 2011