Mormon Classics | "Rigdon Revealed" | Spalding Library | Bookshelf | Newspapers | History Vault

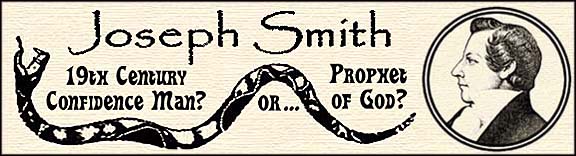

Joseph Smith:

Nineteenth Century Con Man?

By Dale R. Broadhurst

The unOfficial Joseph Smith Memorial Page | Sidney Rigdon: Creating the Book of Mormon

Tracking Book of Mormon Authorship | Word-print Study | Joseph Smith & Sidney Rigdon

Additional Reference Material: Historical Sources | Modern Sources | Herman Melville Items

|

FOR THIS WEB-PAPER ________

|

|

INTRODUCTION

The public career of Joseph Smith, Jr. was short and exceptionally eventful. It began in the late 1820s and ended abruptly, on June 27, 1844

at Carthage Jail. Within those few years, he burst upon the religious-political scene as a purported seer, recipient of visions, translator

of dead languages, revelator of scriptures, president of an Ohio bank, mayor of the largest city in Illinois, and even a would-be candidate

for the presidency of the United States.

and --

In both cases (and in many others on record) the writers on Mormonism cannot avoid addressing the possibility that Joseph Smith, Jr.,

the famous 19th century Mormon leader, might be viewed as a confidence man -- as a sharp operator unworthy of people's

confidence. What exactly does this mean -- for a "man of the cloth" to be typified as an equivocal solicitor

of other men's confidence?

"Confidence Man" (also "Con Man," "Con Artist," etc.) was a term that Joseph Smith, Jr. probably never heard during his lifetime. In his

day, the popular word for a purposeful deceiver was "juggler." This latter description was often applied to the young visionary himself

during the 1830s and 1840s, as an explanation for his unusual ability to gain the trust of a certain group of people, such as the Mormon

Whitmer

family. As Eber D. Howe put it, in 1834: "They were noted in their

neighborhood for credulity and a general belief in witches, and perhaps were fit subjects for the juggling arts of Smith." Although Howe

called Mormonism an imposition, a juggler in Howe's day was not necessarily an impostor. The peddler of medicinal

"rutes and yarbs" might occasionally resort to petty trickery and playing upon customers' superstitions, in order to hawk his suspect

remedies; but such a juggler could also be totally honest about his own identity and personal activities. His salesman's task was

not merely to swindle buyers, but to positively convince them of the importance of things they might otherwise ignore.

More precisely, the "American press" here referred to was, originally, the editor of a widely read newspaper -- James G. Bennett of the New York Herald. On July 8, 1849 he reported:

In subsequent articles, editor Bennett revealed that William Thompson was a seasoned petty criminal who made use of a number of alias

identities. This widely publicized reporting appears to have provided author Herman Melville with the basic plot idea for his 1857 novel,

The Confidence Man: His Masquerade. While Bennett's coining of the designation confidence man might have earned the term

a disreputable entry in American dictionaries without any literary assistance from Melville, the latter author's contribution to popular

language should not be overlooked -- for in reading Melville's puzzling 1857 story we are brought full circle, back to "Joe Smith" and

his Mormon religion.

* See, for example, Robert A. Rees' 1966 paper "Melville's Alma and The Book of Mormon," in Emerson Society Quarterly 43:2, as well as Cecilia K. Farr's 1989 paper "The Philosopher and the Brass Plate: Melville's Quarrel with Mormonism in The Confidence Man," in American Transcendental Quarterly 3:4; also of interest is Richard D. Rust's 2008 paper "'I Love All Men Who Dive': Herman Melville and Joseph Smith" in Reid L. Neilson and Terryl L. Givens (eds.) Joseph Smith, Jr.: Reappraisals After Two Centuries. A more recent, fanciful comparison of Herman Melville and Joseph Smith, Jr. may be found in Martin Blythe's web-page, "The Sorcerer's Apprentice: Melville, Mormons and Moby-Dick." For a detailed account of how the Herald's 1849 reports on William Thompson helped inspire a notable work of 19th century fiction, see Michael S. Reynolds' 1971 paper "The Prototype for Melville's Confidence-Man" in Publications of the Modern Language Association 86:5. |

~ SECTION 1 ~ Counterfeiting Confidence

For most of us the term Confidence Man inevitably summons up mental images of the shifty three card monte dealer, the passer of bogus

currency and the salesman of Brooklyn Bridge deeds -- but such popular stereotypes fail to convey the essential role of the confidence

man. He is the booster of utopias, the solicitor of charitable outpourings, and the repairman of broken dreams. His goal is to instill trust,

hope and gumption in the human bosom. Viewed in this light, the confidence man can, in some situations, be viewed as a benign entity: no

pernicious injury is wrought, unless his conveyed sense of confidence is put to base use (see the Elmer Gantry/Lorenzo Dow comparison

made above). In fact, much good might be done by the confidence man who promotes abiding faith and quintessential self-assurance, at the

right time and in the right place. It can be reasonably argued that many turning points in human advancement depended upon the confident

risk-taking of pioneers and innovators who were convinced to try things new and different.

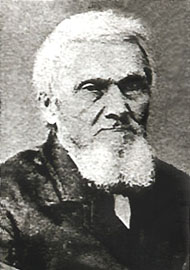

In other words, we are here cautioned against accepting at face value any eye-witness evidence collected and published by D. P. Hurlbut and E. D. Howe, along with the negative conclusions of "every major non-Mormon study from 1834 to the present," whose writers have depended upon the veracity of Hurlbut's investigations and Howe's journalism. Since we might expect the most reliable testimony for (or against) a man's good character to come from eye-witnesses, Richard L. Anderson's argument appears to present an insurmountable barrier to our critical investigation of "Joseph Smith's New York reputation" (for having been a juggler, deceiver, treasure-seer, impostor, etc.). If it was D. P. Hurlbut who originated all the accusations regarding Smith's pretensions to see buried treasures, read people's fortunes, commune with spirits, and such, then perhaps Joseph Smith, Jr. was not a con artist after all.  Eber Dudley Howe (1798-1885) Happily there is a way around this problem, since it is possible to locate statements about "Joe Smith" which pre-date Hurlbut's 1833 evidence gathering and Howe's 1834 publication of such testimony. However, as previously mentioned, we should not expect to run across the exact term confidence man in the early 1830s statements relating to Mr. Smith. As David Persuitte points out:

Persuitte has set us upon the proper path to discovering pre-1834 statements relating to Joseph Smith, Jr.'s reputation. However,

the example he cites from the 1830 Palmyra Reflector,

refers to Walters the Magician, and not to Smith precisely. Unless it can be conclusively demonstrated that a man is known by the

company he keeps (and that Smith and Walters kept close company) we shall have to dig deeper to uncover instances of young

Joseph being called a "juggler," "deceiver," etc.

So, there it is -- a reference to the young Joseph Smith, Jr. being "well known" in the Palmyra area for "juggling," in his

assertions to a supernatural remote-viewing "faculty" and in his pretensions to "the occasional interview" with a treasure-guarding

"spirit." None of which conclusively proves Mr. Cole (whose property was located near the Smith home) to have been an eye-witness,

nor even a reliable reporter of eye-witness accounts related to the first Mormons. What the article does demonstrate, however,

is that Joseph Smith, Jr. was being accused of "juggling" (of being a con man) long before D. P. Hurlbut ever conducted his

anti-Smith interviews in the Palmyra area.

Abner Cole's Palmyra newspaper

The sighting of one robin does not initiate springtime, and the discovery of a single pre-1834 accusation against Joseph Smith, Jr. does not

prove him to have been a 19th century confidence man -- but it does provide an intriguing investigative lead.

Notice that Rev. Sherer also labeled Smith a "juggler," the word then in use for a fraudulent manipulator -- a con man. Rev. Sherer

does not criticize Smith for his pretending to converse with treasure spirits, nor for pretending to work apostolic-style miracles;

(such assertions might be explained away by some modern readers as non-believers' misunderstandings of Smith's real prophetic activities).

Instead, Rev. Sherer brings up a reference to Smith's glass-looking and pretensions of locating buried treasures. It would be

difficult for modern readers to account for these assertions, as having somehow been based upon a misunderstanding of Smith's actual

possession of the biblical "urim and thummim," or of an angel directing him to the location of a buried golden book.

So much for the gift and power of God... It is reported, and probably true, that he commenced his juggling by stealing and hiding property belonging to his neighbors, ... The above statement is more damaging to Smith's early reputation than either the charges of Mr. Cole or Rev. Sherer, for Benton claimed to possess a knowledge of the case presented against the young treasure-seer during his 1826 examination before a Justice of the Peace at Bainbridge, New York. D. Michael Quinn explains the seriousness of the situation:

Smith pretending to see underground through his hat (1904 graphic)

In other words, unless he truly did possess "second sight," what Joseph Smith was doing at the time was illegal, and defined by

the laws of his home state as being the activity of a criminal "juggler" (or con man). Of course many modern defenders of the

man will argue that he really did have the ability to see under the ground, and so he was breaking the law only in a technical

sense. As Oliver Cowdery wrote of Smith in 1835: "while in that

country [Chenengo County in 1826], some very officious person complained of him as a disorderly person, and brought him before the

authorities of the country; but there being no cause of action he was honorably acquited." Cowdery presented no evidence to prove

that Smith was actually acquitted by the court: it appears more likely that he confessed to "glass-looking" and was informally

released (see Rev. Ariel McMaster's July 1881 letter to

the Chicago Interior). At any rate, Joe Smith was acting like other 1820s con men, whom nobody today credits as having been

real treasure-seers. When asked about such reports, in 1838, Smith provided only this scant response: "Was not Joseph Smith a money

digger? -- Yes, but it was never a very profitable job for him, as he got only fourteen dollars a month for it."

Again, unless Joseph Smith, Jr. truly could see underground, he was behaving in a manner exactly such as the New York

laws were written to prohibit. Had he really possessed such occult powers, he might have demonstrated them at his 1826

hearing at Bainbridge, in order to escape condemnation -- instead he ran away, to escape lawful punishment.

In other words, Joseph Smith, Jr. was NOT a "treasure-seeker" nor a treasure-seer, who made use of "a mineral stone... placed in a hat"

to see such riches as "silver bullion" buried in the soil of New York. Instead, he was innocently "saddled" with the bad reputation

of some other local "treasure seeker" peepstone user.

|

~ SECTION 2 ~ JOE SMITH THE SINCERE DECEIVER? Mormons have historically been quick to defend Joseph Smith, Jr., when faced with outsiders' claims that he was an "impostor." This response is understandable, in that questioning Smith's claims to prophethood amounts to questioning the authenticity of Mormonism itself. An example of the LDS response to such questioning is well illustrated in M. Guy Bishop's 1991 Dialogue review of Exiles in a Land of Liberty, (a generally objective history of the early Mormons, written by Kenneth H. Winn):

For M. Guy Bishop, the non-Mormon opposition to Smith's claims to be a revelator of divine communications came from those outsiders'

failure to "comprehend Mormon consecration and communalism." But surely this is an inadequate explanation for the opposition. In fact,

many of the early, outspoken critics of Smith and his religion were former members who fully understood the Latter Day Saint system and

who still disagreed about the true origin of Smith's revelations and teachings. The popular belief in Smith being a con man originated

before the Mormon order was solidified and expanded to significant proportions. It was Smith's observable behavior in his interactions

with people in New York and Pennsylvania which first gained him the reputation of being a con man, and not his role in establishing

the Mormon church. Smith himself must have been aware of this bothersome difficulty, because he dated his first theophany to the year

1820 and explained opposition to his subsequent activities as being Gentile "persecution" of the Mormon religion.

All of this comes from the period after Joseph Smith left New York, to oversee the rise and progress of his church in the West. By that time much of the criticism leveled against him came from observers at a distance who had little understanding of the dynamics of the Mormon "gathering" or of the new sect's internal conflicts. It is, then, no wonder that both Winn and his LDS reviewer are skeptical of Smith's reputation as a con man. The continued growth and expansion of Mormonism seems to argue for some better explanation than simple money-grabbing trickery and popular delusion.  Fawn Brodie's 1945 Smith Biography Battling 21st Century Brodieism A sharper LDS push-back can be found in the apologists' various writings rebutting Fawn M. Brodie's contention -- that Joseph Smith, Jr. "was a self-conscious impostor," (as Dale Morgan once paraphrased her views). A fair specimen of this sort of rebuttal can been seen in Louis Midgley's 2001 review of Newell G. Bringhurst's Brodie biography:

Although ostensibly framed as a summary of historical developments relating to Mrs. Brodie's expressed views, Dr. Midgley's

article accentuates the Latter Day Saint uneasiness with any non-traditional discussion of Smith's motives and methods. The

question of whether or not the "first Mormon" presented "a hoax to the world" takes precedence over any attempt to

discover who the man was and why he behaved as he did. The possibility that Joseph Smith, Jr. may have been something

other than either a traditional prophet or an impostor, appears to elude the Mormon mind.

Well then, where in all of this 21st century revisionism do we find a place for "Joseph Smith: 19th Century Confidence Man?" Has the

question become irrelevant in the post-modernist era? It is doubtful that the thoroughly conservative LDS Church will ever subscribe to

such a notion. "Joe Smith the sincere deceiver" does not look very different from "Joe Smith the disreputable con man" when viewed in

the light of traditional LDS doctrine. But perhaps writers like Bushman are attempting to look beyond the ecclesiastical walls of their

own domain, to make some impression upon "a new breed of 'tolerant' readers" who are never destined to make a personal acquaintance

with an LDS baptismal font. For the benefit of such a class of curious onlookers there may be some value in blurring the lines of

demarcation laid out by Mr. Vogel. Perhaps there is room, somewhere, for "Joseph Smith 4.0" -- the sincere deceiver and conscious

fraud, who inexplicably was also made "a smooth and polished shaft in the quiver of the Almighty."

|

~ SECTION 3 ~ The Melville Archetype The title for this section is taken from a list of over 100 critical studies of Herman Melville's writings, as posted on-line at melville.org. A little more than halfway down that list we find Martin Pops' 1970 volume, The Melville Archetype? The following excerpt, from his page 164, may serve as an introduction to Melville's 1857 Confidence Man as the final specimen among a repeated characterization of tricksters, scattered throughout Melville's several notable works:

Now that readers have been confronted with the shock of this apparent blasphemy, we are ready to examine Melville's "Confidence Man," as presented in the author's mid-19th century novel (if a "novel" it really is).

The book's narration (it can hardly be called a story) takes place during the course of a single day, aboard a riverboat moving southward

from St. Louis toward the seaport of New Orleans. We are not told whether the steamer ever reaches Melville's apocalyptic ocean waters,

hades, or nirvana. The narrative extinguishes itself in the end, with a capricious dollop of ambiguity thrown in for good measure. If the

book's substance bears any resemblance to that of Moby Dick, its nautical allegories are confined to the fluvial microcosm of the

mighty Mississippi.

Such a dark assessment mirrors the editorial offered by James G. Bennett

in 1849, but it does not entirely explain the motives

of Melville's riverboat con men/man. There is more in the book than "everything that is wrong in American society." For example,

in several of the narrated "scams" the con man stands to gain very little, even if his "mark" is totally duped and filled with

counterfeited confidence. In other instances the arguments of the con man, promoting belief, trust, charity and courage will strike

a resonating chord in the soul of the religious believer or the humane philanthropist. Divorced from their petty chicanery, many of

the confidence man's entreaties would make perfectly good sermons.

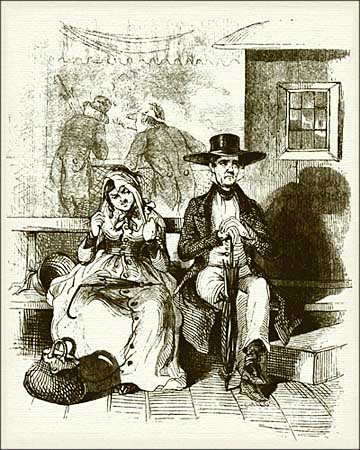

The humorous account goes on to relate how the "Mormon sister" encounters on board a certain man, whom she takes

to be Elder William Smith, younger brother of the late LDS prophet. The spinster sister's overly amiable solicitations

for the man's views relating to "the spiritual system" of plural marriage soon drive the embarrassed fellow away and

the tale comes to a quick ending.

In Melville's version of the tale, it is the man, rather than the woman, on the riverboat full of strangers who

seeks the company of a fellow member of "the Church." As in the 1845 account, the newly met couple sit side by

side and carry on a halting conversation relating to Christian virtue or charity. The man himself is a vague

person -- identified by some passengers under one description, and by others under an alternate description. In

both stories the ostensible male character (an advocate for widows and orphans, and the presumed LDS apostle)

turn out to be something other than they appear to be. One is a shady guy, professing to be a charity worker, while

the other is something like his opposite -- an innocent traveler mistakenly supposed to be the shady William Smith

of Nauvoo.

John S. Robb's "Spiritual Sister" and her "William Smith" (1847)

The intriguing possibility comes to mind, that perhaps Melville was initially planning to write a story with a Mississippi

riverboat setting, including Mormon characters, when his attention was drawn to the 1849 New York Herald's report

of William Thompson, the original "Confidence Man." Thompson's repeated question, "have you confidence in me to trust me...?,"

is inserted almost verbatim into Melville's story as: "Could you put confidence in me...?" One possibility is that

Melville, around 1848-49, had already imagined such a fictional encounter aboard a steamship, and then added to that plot his

paraphrase of the New York confidence man's perennial query. If this were the case, then that ""have you confidence?" question

would easily been connected with a supposed traveling Mormon apostle or prophet -- a religious salesman whose pietistic

message and churchly system demanded a unique degree of members' trust.

Here E. D. Howe implies that the Book of Mormon's eternal "Three Nephites" could only "perpetuate" their race through sexual

intercourse with the cursed (and forbidden) Lamanite women. History does not record whether Howe was also making a subtle reference

to the "reproach" soon afterward admitted to by the Mormons, on page 251 of the 1835 LDS Doctrine and Covenants: "Inasmuch

as this church of Christ has been reproached with the crime of fornication, and polygamy: we declare that we believe, that one man

should have one wife..." Certainly such a "reproach" might easily be applied to a charged leveled against a Mormon member for

engaging in a "crim. con." seduction.

Although the newspaper notice does not directly accuse Brigham Young of having been a con man, in his seduction of Mrs. Cobb,

the deception typically associated with a "crim. con." is implied in the words "led away with Mormonism." Had he been asked

the question in 1844, Henry Cobb probably would have applied the charge of "deceiver" to the already married Brigham Young.

What makes the Mormon apostle's case different from the average "crim. con." of that day, is that he evidently did not deceive

Mrs. Cobb about his marital status, nor about his intention to eventually marry her as a Mormon plural wife. The deception

Mr. Cobb might have pointed to was Brigham's assertion that LDS spiritual wifery existed in obedience to latter day divine

commandments. If Mormon apostles can rightfully be accused as con men, then the most serious charge that could be brought against

them is that they prey upon their converts under the false authority of fabricated divine commandments.

|

|

If it is possible to separate the benign confidence man from the greedy grifter and the malicious imposter, the next question one might ask, is where do confidence men (and confidence women) come from? Well before the "tools of the trade" are acquired (perhaps via the instruction of an experienced confidence man mentor), the young candidate for this shady role in society must start out with some predisposition to influence the opinions and actions of others. One possibility is that the incipient con man is unsettled by disharmony, contention and unpredictable actions among his childhood neighbors and family. In that case, the developing confidence man would naturally be inclined to promote harmony and human charity -- if only to insure his own security and sense of well-being. Another possibility is that the future con man lacks the faculty of a conscience, or is unable to distinguish between reality and imagination. In that case he might develop a narcissistic personality disorder, whereby he can only deal effectively with other people by manipulating them to accept his own distorted views. At any rate, the typical con man continually attempts to influence others to believe things they might not otherwise accept. Human nature being what it is, this manipulative predisposition may easily generate deception, dishonesty and a magnified sense of self-importance. So long as people are inclined to believe in the confidence man, he may be able to promote a general atmosphere of harmony and industrious incentive among those who trust in him. If the con man attributes these positive influences to a "higher power," he may also find himself in a position of considerable authority. It appears, however, that such religious-political successes are human rarities. Perhaps, in the long run, the truly honest and non-manipulative leaders tend to regularly occupy the social niches that self-motivated con men can only expect to gain and hold temporarily. Such leadership positions may initially be acquired through deception, but continual deception of a leader, unbuttressed by tyranny, can only be maintained through increased deception. Like any Ponzi schemer, such a leader is eventually exposed by an implosion of his own authority system. Joseph Smith, Jr. suffered through partial implosions of Mormonism in Ohio, Missouri and Illinois, but still managed to maintain his authoritarian religious system to the very end of his life -- in fact, the system survived his own demise. This development cannot be attributed solely to the exercise of ecclesiastical tyranny, so it might thus be used as one argument against Smith having been a true confidence man. Can we justify the equivocal efforts of influential confidence men, based upon testimony of their ultimate goodness? The great philosophies and religions of the world tell us that expected positive results do not justify their means of enactment -- when those means are dishonest or immoral. If this be true, then the most that a cynic might say on behalf of the confidence man's positive outcomes, is that he is the product of the world and that he survives in the world by whatever actions work for him. If his deceptive efforts now and then help produce postive results, it does not follow that confidence schemes are the best means for reaching good ends. If the illegitimate actions of a con man cannot be justified by their hoped-for good consequences, then perhaps an alternative rationalization remains. Perhaps people get "what they deserve" and the con man is justified by the precept that he is no worse than anybody else. At first glance, this alternative appears to fit well with the Mormon teaching of a Great Apostasy, in which all true religious authority disappeared from the earth centuries ago. Viewing human society from that perspective, the actions of a con man would be, at the very worst, the moral equivalent of hypocritical "hireling priests," and perhaps, ultimately, something far better. The Book of Mormon teaches "every thing which inviteth to do good, and to persuade to believe in Christ, is sent forth by the power and gift of Christ; wherefore ye may know with a perfect knowledge it is of God" (Moroni 7:16, LDS edition). Evidently, in a thoroughly wicked world the con man's solicitations "to do good" and "to believe" might be "of God," even if his message is instilled through lying, cheating, and stealing. Consider Yvonne E. Pelletier's summary of Herman Melville's The Confidence-Man:

Perhaps Joseph Smith was not a Con Man After All?

A Third Possibility: From Occult to Cult

Having thus branded the young Joseph Smith as a criminal running "a confidence game," Rev. Walters goes on to describe Smith as "a young 'glass-looking' confidence man" and an occultist who blended "religion and magic" in order to "make his confidence game seem more convincing" among his money-digging dupes. Walters adds a surprising twist to the above summary of Smith's 1820s practice of magical chicanery by concluding, "he came at least half-way to believe in that realm of the occult." He also says this about Smith's second encounter with the Law in southern upstate New York:

Rev. Walters' theory regarding Joseph Smith's transformation from con man to would-be prophet is an important statement. Whether or

not this summary accurately fits Smith's development into the foremost LDS leader, it provides the basis for a third alternative

to the deceiver/truth-teller dichotomy so often encountered in Smith biographies. To some extent Rev. Walters' theory parallels

Fawn Brodie's belief, that Smith was a "conscious impostor" who came to believe himself a prophet. Both of these views are somewhat

compatible with Dan Vogel's deduction, that Smith was a "pious fraud" who became a prophetic religion-founder. What Walters' theory

adds to all of this, is the unique observation that a small town con man made a "successful transition from a practitioner of the

occult, searching for money, to the prophet of the new cult of Mormonism." Walters thus applies Smith's experimentation with magic

as a sort of psychic catalyst -- a motivation and methodology which propelled the Palmyra farmboy into a role transcending that of

a commonplace con man who had been pretending to be a treasure seer and fortune teller.

Craig Criddle's estimation of Joseph Smith being a purposeful deceiver still allows for him to have been the sole author of the Book of

Mormon (though Criddle elsewhere argues against the Smith-alone authorship theory). It also allows for Smith to have been sincerely

convinced of his purported supernatural powers and to have evolved into a miracle-worker. But even after these theoretical concessions,

Criddle still labels the Mormon leader as a con man, due the "ruses used by Smith to con people." In other words, Joseph Smith, Jr.

was something much more complex than a "run-of-the mill con man," and he may well have believed in his own seership. The distinguishing

feature which nevertheless marks Smith as a probable confidence man was his "remarkable ability to induce and retain belief" in his

followers, by "performing tricks that appear[ed] to be miracles."

|

~ SECTION 5 ~ 5 Melville Mormons and Mardi The title for this section is shamelessly plagiarized from Martin Blythe's web-page subtitle, "Melville, Mormons and Moby-Dick," and rests upon the determination that Herman Melville knew more than a little about Mormonism and that he dropped hints of that knowledge in various fictional writings, beginning with his singular novel Mardi, first published in 1849. The novel has about as many interpretations as it has had readers, but an agreement can probably be reached upon its primary theme -- which is the search for truth amongst the tangles and tatters of religious mythology. Set in an improbable part of Polynesia, the story tells of voyages between fictional islands, inhabited by fictional peoples, believing and carrying on a bewildering variety of mythical traditions, some of which are manifested in fanciful religious tenets and practices. Mormonism is not one of those traditions, but fragments of the latter day infatuation may be discovered, scattered through the pages and isles comprising imaginary Mardi. One lesson the discerning reader may learn from Melville's story, is that truth will not be found in any one particular religious mythology. All the mythologies are in competetion to communicate the truth, and they obviously cannot all be correct in their sundry messages. Even where the truth appears to momentarily shine through the clouds of dubious tradition, we may well suspect that it will be misunderstood, perverted and eventually lost sight of. Whether communicated through the medium of history, legend, poetry or reason, it is likely that the self-styled truth-tellers will disagree in their message and accuse one another of misrepresentations, errors and fictions. So, what value can the seeker of truth take away from his investigation? Perhaps this: No one source will supply the perfect answer, but a comparison of all the sources will at least convey the veritable fact that truth is elusive. This realization has intrinsic value and may help point the seeker in the right direction, whereby he can eventually stumble upon the truth, and know it by direct experience, rather than by unreliable instruction. But what has all of that to do with Mormonism? |

(remainder of text under construction -- to be totally revised)

~ SECTION 6 ~ 6 |

~ SECTION 7 ~ 7 Joseph Smith and the Origins of the Book of Mormon By David Persuitte In one of his articles in the Palmyra Reflector, Obediah Dogberry mentioned a "juggler" named Walters who was employed by the local company of money diggers. (The word "juggler" was then used to denote someone who manipulated people for fraudulent purposes. The current term would be "con man." =================== Mormonism Unvailed -- juggling for money =================== The synonym finder By Nancy LaRoche, Laurence Urdang juggler -- trickster, deceiver, deluder, beguiler, bamboozler, cheat, swindler, defrauder, double-dealer, sharp, sharper, flimflam man, con man, con artist, imposter, fraud, fake, phony, charlatan, mountbank, quack, quick change artist ======================= ============================== ============================== Evangelical Magazine and Gospel Advocate April 9, 1831 It is reported, and probably true hut he commenced hit* juggling by stealing and hiding property belonging lo his neighbors, . =============================== Mormonism in All Ages: Or, the Rise, Progress, and Causes of Mormonism with ...? - Page 301 ??? by Jonathan Baldwin Turner ================================= The Prophet of the Nineteenth Century: Or, The Rise, Progress, and Present ...? - by Henry Caswall 1843 Page vi ... and for the circumstance, otherwise inexplicable, of a low juggler, without character, without education, without common prudence or decency, ================================= |

|

8 ====================== Although Brodie thought Nixon an imposter like Joseph Smith, she did not believe him to be the "charming imposter the Mormon leader was."[54 Bringhurst, 224-26] Mormon History By Ronald Warren Walker, David J. Whittaker, James B. Allen p. 46-47 -- Brodie ====================== ========================== Joseph Smith, the great American impostor; or, Mormonism proved to be false By Thomas Tyson ========================== |

OPENING NEW HORIZONS IN MORMON HISTORY