Mormon Classics | "Rigdon Revealed" | Spalding Library | Bookshelf | Newspapers | History Vault

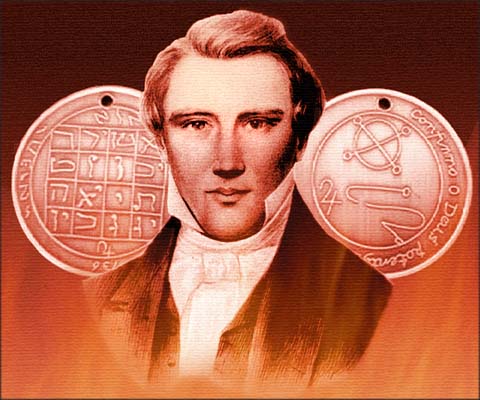

Joseph Smith:

Nineteenth Century Con Man?

By Dale R. Broadhurst

The unOfficial Joseph Smith Memorial Page | Sidney Rigdon: Creating the Book of Mormon

Tracking Book of Mormon Authorship | Word-print Study | Joseph Smith & Sidney Rigdon

Additional Reference Material: Historical Sources | Modern Sources | Herman Melville Items

|

FOR THIS WEB-PAPER ________

|

|

INTRODUCTION

The public career of Joseph Smith, Jr. was short and exceptionally eventful. It began in the late 1820s and ended abruptly, on June 27, 1844

at Carthage Jail. Within those few years, he burst upon the religious-political scene as a purported seer, recipient of visions, translator

of dead languages, revelator of scriptures, president of an Ohio bank, mayor of the largest city in Illinois, and even a would-be candidate

for the presidency of the United States.

and --

In both cases (and in many others on record) the writers on Mormonism cannot avoid addressing the possibility that Joseph Smith, Jr.,

the famous 19th century Mormon leader, might be viewed as a confidence man -- as a sharp operator unworthy of people's

confidence. What exactly does this mean -- for a "man of the cloth" to be typified as an equivocal solicitor

of other men's confidence?

"Confidence Man" (also "Con Man," "Con Artist," etc.) was a term that Joseph Smith, Jr. probably never heard during his lifetime. In his

day, the popular word for a purposeful deceiver was "juggler." Although the meanings of these two terms are not identical, a modern con

man would have been most recognizable in Smith's day as a "juggler." The latter description was often applied to the young visionary

himself during the 1830s and 1840s, as an explanation for Smith's unusual ability to gain the trust of a certain group of people, such as

the Mormon Whitmer family. As Eber D. Howe put it,

in 1834: "They were noted in their neighborhood for credulity and a general

belief in witches, and perhaps were fit subjects for the juggling arts of Smith." Although Howe called Mormonism an imposition, a

juggler in Howe's times was not necessarily an impostor. The peddler of medicinal "rutes and yarbs" might occasionally resort

to petty trickery and playing upon customers' superstitions, in order to hawk his suspect remedies; but such a juggler could also be

totally honest about his own identity and personal activities. His salesman's task was not merely to swindle buyers, but to positively

convince them of the importance of things they might otherwise ignore.

More precisely, the "American press" here referred to was, originally, the editor of a widely read newspaper -- James G. Bennett of the New York Herald. On July 8, 1849 he reported:

In subsequent articles, editor Bennett revealed that William Thompson was a seasoned petty criminal who made use of a number of alias

identities. This widely publicized reporting appears to have provided author Herman Melville with the basic plot idea for his 1857 novel,

The Confidence Man: His Masquerade. While Bennett's coining of the designation confidence man might have earned the term

a disreputable entry in American dictionaries without any literary assistance from Melville, the latter author's contribution to popular

language should not be overlooked -- for in reading Melville's puzzling 1857 story we are brought full circle, back to "Joe Smith" and

his Mormon religion.

* See, for example, Robert A. Rees' 1966 paper "Melville's Alma and The Book of Mormon," in Emerson Society Quarterly 43:2, as well as Cecilia K. Farr's 1989 paper "The Philosopher and the Brass Plate: Melville's Quarrel with Mormonism in The Confidence Man," in American Transcendental Quarterly 3:4; also of interest is Richard D. Rust's 2008 paper "'I Love All Men Who Dive': Herman Melville and Joseph Smith" in Reid L. Neilson and Terryl L. Givens (eds.) Joseph Smith, Jr.: Reappraisals After Two Centuries. A more recent, fanciful comparison of Herman Melville and Joseph Smith, Jr. may be found in Martin Blythe's web-page, "The Sorcerer's Apprentice: Melville, Mormons and Moby-Dick." For a detailed account of how the Herald's 1849 reports on William Thompson helped inspire a notable work of 19th century fiction, see Michael S. Reynolds' 1971 paper "The Prototype for Melville's Confidence-Man" in Publications of the Modern Language Association 86:5. |

~ SECTION 1 ~ Counterfeiting Confidence

For most of us the term Confidence Man probably summons up mental images of the shifty three card monte dealer, the passer of bogus

currency and the salesman of Brooklyn Bridge deeds -- but such popular stereotypes fail to convey the essential role of the confidence

man. He is the booster of utopias, the solicitor of charitable outpourings, and the repairman of broken dreams. His goal is to instill trust,

hope and gumption in the human bosom. Viewed in this light, the confidence man can, in some situations, be viewed as a benign entity: no

pernicious injury is wrought, unless his conveyed sense of confidence is put to base use (see the Elmer Gantry/Lorenzo Dow comparison

made above). In fact, much good might be done by the confidence man who promotes abiding faith and quintessential self-assurance, at the

right time and in the right place. It can be reasonably argued that many turning points in human advancement depended upon the confident

risk-taking of pioneers and innovators who were convinced to try things new and different.

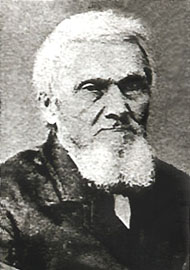

In other words, we are here cautioned against accepting at face value any eye-witness evidence collected and published by D. P. Hurlbut and E. D. Howe, along with the negative conclusions of "every major non-Mormon study from 1834 to the present," whose writers have depended upon the veracity of Hurlbut's investigations and Howe's journalism. Since we might expect the most reliable testimony for (or against) a man's good character to come from eye-witnesses, Richard L. Anderson's argument appears to present an insurmountable barrier to our critical investigation of "Joseph Smith's New York reputation" (for having been a juggler, deceiver, treasure-seer, impostor, etc.). If it was D. P. Hurlbut who originated all the accusations regarding Smith's pretensions to see buried treasures, read people's fortunes, commune with spirits, and such, then perhaps Joseph Smith, Jr. was not a con artist after all.  Eber Dudley Howe (1798-1885) Happily there is a way around this problem, since it is possible to locate statements about "Joe Smith" which pre-date Hurlbut's 1833 evidence gathering and Howe's 1834 publication of such testimony. However, as previously mentioned, we should not expect to run across the exact term confidence man in the early 1830s statements relating to Mr. Smith. As David Persuitte points out:

Persuitte has set us upon the proper path to discovering pre-1834 statements relating to Joseph Smith, Jr.'s reputation. However,

the example he cites from the 1830 Palmyra Reflector,

refers to Walters the Magician, and not to Smith precisely. Unless it can be conclusively demonstrated that a man is known by the

company he keeps (and that Smith and Walters kept close company) we shall have to dig deeper to uncover instances of young

Joseph being called a "juggler," "deceiver," etc.

So, there it is -- a reference to the young Joseph Smith, Jr. being "well known" in the Palmyra area for "juggling," in his

assertions to a supernatural remote-viewing "faculty" and in his pretensions to "the occasional interview" with a treasure-guarding

"spirit." None of which conclusively proves Mr. Cole (whose property was located near the Smith home) to have been an eye-witness,

nor even a reliable reporter of eye-witness accounts related to the first Mormons. What the article does demonstrate, however,

is that Joseph Smith, Jr. was being accused of "juggling" (of being something very much like a con man) long before D. P. Hurlbut

ever conducted his anti-Smith interviews in the Palmyra area.

Abner Cole's Palmyra newspaper

The sighting of one robin does not initiate springtime, and the discovery of a single pre-1834 accusation against Joseph Smith, Jr. does not

prove him to have been a 19th century confidence man -- but it does provide an intriguing investigative lead.

Notice that Rev. Sherer also labeled Smith a "juggler," the word then in use for a fraudulent manipulator -- essentially a con man. Rev.

Sherer does not criticize Smith for his pretending to converse with treasure spirits, nor for pretending to work apostolic-style miracles;

(such assertions might be explained away by some modern readers as non-believers' misunderstandings of Smith's real prophetic activities).

Instead, Rev. Sherer brings up a reference to Smith's glass-looking and pretensions of locating buried treasures. It would be

difficult for modern readers to account for these assertions, as having somehow been based upon a misunderstanding of Smith's actual

possession of the biblical "urim and thummim," or of an angel directing him to the location of a buried golden book.

While it does not rise to the level of proof, the above statement is more damaging to Smith's early reputation than either the charges of Mr. Cole or Rev. Sherer, for Benton claimed to possess a knowledge of the case presented against the young treasure-seer during his 1826 examination before a Justice of the Peace at Bainbridge, New York. D. Michael Quinn explains the seriousness of the situation:

Smith pretending to see underground through his hat (1904 graphic)

In other words, unless he truly did possess "second sight," what Joseph Smith was doing at the time was illegal, and defined by the laws

of his home state as being the activity of a criminal "juggler" (essentially a con man). Of course many modern defenders of the

man will argue that he really did have the ability to see under the ground, and so he was breaking the law only in a technical

sense. As Oliver Cowdery wrote of Smith in 1835: "while in that

country [Chenengo County in 1826], some very officious person complained of him as a disorderly person, and brought him before the

authorities of the country; but there being no cause of action he was honorably acquited." Cowdery presented no evidence to prove

that Smith was actually acquitted by the court: it appears more likely that he confessed to "glass-looking" and was informally

released (see Rev. Ariel McMaster's July 1881 letter to

the Chicago Interior and "The Original Prophet" in Fraser's Magazine for

Feb., 1873, p. 229).

Again, unless Joseph Smith, Jr. truly could see underground, his reported behavior was exactly such as the New York

laws were written to prohibit. Had he really possessed such occult powers, he might have demonstrated them at his 1826

Justice's examination at Bainbridge, in order to escape condemnation -- instead he ran away, to escape lawful punishment.

In other words, Joseph Smith, Jr. was not a "treasure-seeker" nor a treasure-seer, who made use of "a mineral stone... placed in

a hat" to see such riches as "silver bullion" buried in the soil of New York. Instead, he was innocently "saddled" with the bad reputation

of some other local "treasure seeker" peepstone user.

|

~ SECTION 2 ~ Joe Smith: the Sincere Deceiver? Mormons have historically been quick to defend Joseph Smith, Jr., when faced with outsiders' claims that he was an "impostor." This response is understandable, in that questioning Smith's claims to prophethood amounts to questioning the authenticity of Mormonism itself. An example of the LDS response to such questioning is well illustrated in M. Guy Bishop's 1991 Dialogue review of Exiles in a Land of Liberty, (a generally objective history of the early Mormons, written by Kenneth H. Winn):

For M. Guy Bishop, the non-Mormon opposition to Smith's claims to be a revelator of divine communications came from those outsiders'

failure to "comprehend Mormon consecration and communalism." But surely this is an inadequate explanation for the opposition. In fact,

many of the early, outspoken critics of Smith and his religion were former members who fully understood the Latter Day Saint system and

who still disagreed about the true origin of Smith's revelations and teachings. The popular belief in Smith being a con man originated

before the Mormon order was solidified and expanded to significant proportions. It was Smith's observable behavior in his interactions

with people in New York and Pennsylvania which first gained him the reputation of being a con man, and not his role in establishing

the Mormon church. Smith himself must have been aware of this bothersome difficulty, because he dated his first theophany to the year

1820 and explained opposition to his subsequent activities as being Gentile "persecution" of the Mormon religion.

All of this comes from the period after Joseph Smith left New York, to oversee the rise and progress of his church in the West. By that time much of the criticism leveled against him came from observers at a distance who had little understanding of the dynamics of the Mormon "gathering" or of the new sect's internal conflicts. It is, then, no wonder that both Winn and his LDS reviewer are skeptical of Smith's reputation as a con man. The continued growth and expansion of Mormonism seems to argue for some better explanation than simple money-grabbing trickery and popular delusion.  Fawn Brodie's 1945 Smith Biography Battling 21st Century Brodieism A sharper LDS push-back can be found in the apologists' various writings rebutting Fawn M. Brodie's contention -- that Joseph Smith, Jr. "was a self-conscious impostor," (as Dale Morgan once paraphrased her views). A fair specimen of this sort of rebuttal can been seen in Louis Midgley's 2001 review of Newell G. Bringhurst's Brodie biography:

Although ostensibly framed as a summary of historical developments relating to Mrs. Brodie's expressed views, Dr. Midgley's

article accentuates the Latter Day Saint uneasiness with any non-traditional discussion of Smith's motives and methods. The

question of whether or not the "first Mormon" presented "a hoax to the world" takes precedence over attempts to independently

discover who the man was and why he behaved as he did. The possibility that Joseph Smith, Jr. may have been something

other than either a traditional prophet or an impostor, appears to elude the Mormon mind.

The Need for a New Rubric

If the old attempts at defining Joseph Smith, Jr. as something other than a prophet are no longer useful, then what new definition

might we plausibly attach to him? If "con man" stands at the lower end of a scale, and "prophet" stands at the higher end, are there

any mediatory possibilities between these two extremes? Dan Vogel's "pious fraud" category merges into the definition of "prophet;"

and the term "con man" can be extended to the pretensions of "religious fraud." Between the religious fraud of an unbeliever and

the pious fraud of an unscrupulous believer, is there any place for Joseph Smith, Jr.? Upon careful consideration, there appears to

be no simple definition for the man -- that is, no credible explanation for the non-Mormon to fall back upon with any assurance.

Well then, where in all of this 21st century revisionism do we find a place for "Joseph Smith: 19th Century Confidence Man?" Has the

question become irrelevant in the post-modernist era? It is doubtful that the thoroughly conservative LDS Church will ever subscribe to

such a notion. "Joe Smith the sincere deceiver" does not look very different from "Joe Smith the disreputable con man" when viewed in

the light of traditional LDS doctrine. But perhaps writers like Bushman are attempting to look beyond the ecclesiastical walls of their

own domain, to make some impression upon "a new breed of 'tolerant' readers" who are never destined to make a personal acquaintance

with an LDS baptismal font. For the benefit of such a class of curious onlookers there may be some value in blurring the lines of

demarcation laid out by Mr. Vogel. Perhaps there is room, somewhere, for "Joseph Smith 4.0" -- the sincere deceiver and conscious

fraud, who inexplicably was also made "a smooth and polished shaft in the quiver of the Almighty."

|

~ SECTION 3 ~ The Melville Archetype The title for this section is taken from a list of over 100 critical studies of Herman Melville's writings, as posted on-line at melville.org. A little more than halfway down that list we find Martin Pops' 1970 volume, The Melville Archetype? The following excerpt, from his page 164, may serve as an introduction to Melville's 1857 Confidence Man as the final specimen among a repeated characterization of tricksters, scattered throughout Melville's several notable works:

Now that readers have been confronted with the shock of this apparent blasphemy, we are ready to examine Melville's "Confidence Man," as presented in the author's mid-19th century novel (if a "novel" it really is).

The book's narration (it can hardly be called a story) takes place during the course of a single day, aboard a riverboat moving southward

from St. Louis toward the seaport of New Orleans. We are not told whether the steamer ever reaches Melville's apocalyptic ocean waters,

hades, or nirvana. The narrative extinguishes itself in the end, with a capricious dollop of ambiguity thrown in for good measure. If the

book's substance bears any resemblance to that of Moby Dick, its nautical allegories are confined to the fluvial microcosm of the

mighty Mississippi.

Such a dark assessment mirrors the editorial offered by James G. Bennett

in 1849, but it does not entirely explain the motives

of Melville's riverboat con men/man. There is more in the book than "everything that is wrong in American society." For example,

in several of the narrated "scams" the con man stands to gain very little, even if his "mark" is totally duped and filled with

counterfeited confidence. In other instances the arguments of the con man, promoting belief, trust, charity and courage will strike

a resonating chord in the soul of the religious believer or the humane philanthropist. Divorced from their petty chicanery, many of

the confidence man's entreaties would make perfectly good sermons.

The humorous account goes on to relate how the "Mormon sister" encounters on board a certain man, whom she takes

to be Elder William Smith, younger brother of the late LDS prophet. The spinster sister's overly amiable solicitations

for the man's views relating to "the spiritual system" of plural marriage soon drive the embarrassed fellow away and

the tale comes to a quick ending.

In Melville's version of the tale, it is the man, rather than the woman, on the riverboat full of strangers who

seeks the company of a fellow member of "the Church." As in the 1845 account, the newly met couple sit side by

side and carry on a halting conversation relating to Christian virtue or charity. The man himself is a vague

person -- identified by some passengers under one description, and by others under an alternate description. In

both stories the ostensible male character (an advocate for widows and orphans, and the presumed LDS apostle)

turns out to be something other than he appears to be. One is a shady guy, professing to be a charity worker, while

the other is something like his opposite -- an innocent traveler mistakenly supposed to be the shady William Smith

of Nauvoo.

John S. Robb's "Spiritual Sister" and her "William Smith" (1847)

The intriguing possibility comes to mind, that perhaps Melville was initially planning to write a story with a Mississippi

riverboat setting, including Mormon characters, when his attention was drawn to the 1849 New York Herald's report

of William Thompson, the original "Confidence Man." Thompson's repeated question, "have you confidence in me to trust me...?,"

is inserted almost verbatim into Melville's story as: "Could you put confidence in me...?" One possibility is that

Melville, around 1848-49, had already imagined such a fictional encounter aboard a steamship, and then added to that plot his

paraphrase of the New York confidence man's perennial query. If this were the case, then that ""have you confidence?" question

would easily been connected with a supposed traveling Mormon apostle or prophet -- a religious salesman whose pietistic

message and churchly system demanded a unique degree of members' trust.

Here E. D. Howe implies that the Book of Mormon's eternal "Three Nephites" could only "perpetuate" their race through sexual

intercourse with the cursed (and forbidden) Lamanite women. History does not record whether Howe was also making a subtle reference

to the "reproach" soon afterward admitted to by the Mormons, on page 251 of the 1835 LDS Doctrine and Covenants: "Inasmuch

as this church of Christ has been reproached with the crime of fornication, and polygamy: we declare that we believe, that one man

should have one wife..." Certainly such a "reproach" might easily be applied to a charged leveled against a Mormon member for

engaging in a "crim. con." seduction.

Although the newspaper notice does not directly accuse Brigham Young of having been a con man, in his seduction of Mrs. Cobb,

the deception typically associated with a "crim. con." is implied in the words "led away with Mormonism." Had he been asked

the question in 1844, Henry Cobb probably would have applied the charge of "deceiver" to the already married Brigham Young.

What makes the Mormon apostle's case different from the average "crim. con." of that day, is that he evidently did not deceive

Mrs. Cobb about his marital status, nor about his intention to eventually marry her as a Mormon plural wife. The deception

Mr. Cobb might have pointed to was Brigham's assertion that LDS spiritual wifery existed in obedience to latter day divine

commandments. If Mormon apostles can rightfully be accused as con men, then the most serious charge that could be brought against

them is that they prey upon their converts under the false authority of fabricated divine commandments.

|

|

If it is possible to separate the benign promoter of confidence from the greedy grifter and the malicious imposter, the next question

one might ask, is where do confidence men (and confidence women) come from? Well before the "tools of the trade" are acquired (perhaps

via the instruction of an experienced confidence man mentor), the young candidate for this shady role in society must start out with

some predisposition to influence the opinions and actions of others. One possibility is that the incipient con man is unsettled by

disharmony, contention and unpredictable actions among his childhood neighbors and family. In that case, the developing confidence man

would naturally be inclined to promote harmony and human charity -- if only to insure his own security and sense of well-being.

Another possibility is that the future con man lacks the faculty of a conscience, or is unable to distinguish between reality and

imagination. In that case he might develop a narcissistic personality disorder, whereby he can only deal effectively with other people by

manipulating them to accept his own distorted views. At any rate, the typical con man continually attempts to influence others to believe

things they might not otherwise accept. Human nature being what it is, this manipulative predisposition may easily generate deception,

dishonesty and a magnified sense of self-importance.

Perhaps Joseph Smith was Not a Con Man After All?

A Third Possibility: From Occult to Cult

Having thus branded the young Joseph Smith as a criminal running "a confidence game," Rev. Walters goes on to describe Smith as "a young 'glass-looking' confidence man" and an occultist who blended "religion and magic" in order to "make his confidence game seem more convincing" among his money-digging dupes. Walters adds a surprising twist to the above summary of Smith's 1820s practice of magical chicanery by concluding, "he came at least half-way to believe in that realm of the occult." He also says this about Smith's second encounter with the Law in southern upstate New York:

Rev. Walters' theory regarding Joseph Smith's transformation from con man to would-be prophet is an important statement. Whether or

not this summary accurately fits Smith's development into the foremost LDS leader, it provides the basis for a third alternative

to the deceiver/truth-teller dichotomy so often encountered in Smith biographies. To some extent Rev. Walters' theory parallels

Fawn Brodie's belief, that Smith was a "conscious impostor" who came to believe himself a prophet. Both of these views are somewhat

compatible with Dan Vogel's deduction, that Smith was a "pious fraud" who became a prophetic religion-founder. What Walters' theory

adds to all of this, is the unique observation that a small town con man made a "successful transition from a practitioner of the

occult, searching for money, to the prophet of the new cult of Mormonism." Walters thus applies Smith's experimentation with magic

as a sort of psychic catalyst -- a motivation and methodology which propelled the Palmyra farmboy into a role transcending that of

a commonplace con man who had been pretending to be a treasure seer and fortune teller.

The ambiguity of Smith's choice of confidence-building techniques, before, during and after his supposed religious transformation is what makes it difficult to establish any particular chronological point at which he ceased being a con man and began being a "true prophet." Craig Criddle, in his examination of Smith's probable contribution to bringing forth the Book of Mormon, bypasses this problem, by focusing attention only upon Smith's activities prior to the publication of that book. He says:

Craig Criddle's estimation of Joseph Smith being a purposeful deceiver still allows for him to have been the sole author of the Book of

Mormon (though Criddle elsewhere argues against the Smith-alone authorship theory).

It also allows for Smith to have been sincerely convinced of his purported supernatural powers and to have evolved into a miracle-worker.

But even after these theoretical concessions, Criddle still labels the Mormon leader as a con man, due the "ruses used by Smith to con

people." In other words, Joseph Smith, Jr. was something much more complex than a "run-of-the mill con man," and he may well have believed

in his own seership. The distinguishing feature which nevertheless marks Smith as a probable confidence man was his "remarkable ability to

induce and retain belief" in his followers, by "performing tricks that appear[ed] to be miracles."

|

~ SECTION 5 ~ Melville Mormons and Mardi

The title for this section is shamelessly plagiarized from Martin Blythe's

web-page subtitle, "Melville, Mormons and Moby-Dick," and rests

upon the determination that Herman Melville knew more than a little about Mormonism and that he dropped hints of that knowledge in

various fictional writings, beginning with his singular novel Mardi, first published in 1849.

Rees goes on to present several convincing arguments in favor of Herman Melville having been a Book of Mormon reader and a novelist

whose books indicate that he was familiar with early Mormonism. Rees also discusses in detail how Melville's reading of the Book of Mormon

may have influenced his creating the ancient Polynesian character "Alma" in the novel Mardi. Melville's "illustrious prophet" Alma

never appears in the flesh in Mardi, but he is much

spoken of there -- not only as a prophet of the olden days,

but also as an actual incarnation of the supreme Mardian deity. Alma in the novel was the final and most perfect human revelation of the

One True God. He thus stands as a close parallel with the biblical Jesus Christ.

Here then is a hint as to how Melville may have stumbled upon the Book of Mormon, wherein one of "the world's savior gods" is depicted as the risen Christ, visiting the American Nephites. In pre-colonial Peru, another of those "world's savior gods" was Manco Capac, a semi-mythological figure whose legends Mormons point to, as preserving a vestige of the Christ among the Nephites story. Martin Blythe notices the importance of this Peruvian connection, in his remarks concerning Melville's The Confidence-Man:

If Melville bothered to read both the Book of Mormon and some mid-19th century LDS faith-promoting literature, he would have realized that the Latter Day Saints point out the book's account of the Nephite Hagoth sailing off into the unknown seas as the means by which Polynesia was populated by proto-Christian Israelites. Although Hagoth's voyage ostensibly came before Christ's visit to America, subsequent Nephite/Lamanite navigators could have followed in his wake, carrying the Manco Capac corruption of Christianity to Melville's fictional version of Polynesia. While LDS publications in the 1850s did not prominently accentuate the "Quetzalcoatl-like American gods," Melville could have made the necessary mental connection, simply by reading 3rd Nephi in the Book of Mormon, along with any number of volumes on preColumbian American religion -- Lord Kingsborough's Antiquities of Mexico would have offered sufficient source material for Melville to have linked the "Quetzalcoatl-like gods" to 3rd Nephi's American Christ. In fact, the popular magazines of the 1850s could have supplied Melville with a good deal of information for his novels. The Oct., 1855 issue of Putnam's Monthly contained not only the first installment of Melville's own Benito Cereno, but also an episode of the serialized "Life Among the Mormons." The previous month's issue contained another Mormon episode, as well as a statement identifying the "mysterious personage" of Quetzalcoatl as "the Buddha of the Mexicans." Manco Capac and Mama Ocllo, by LDS Artist George M. Ottinger

In Melville's Mardi, "Manko" is the avatar who appeared immediately prior to Alma (who was the final Divine incarnation). If

"Manko" (Manco Capac) came across the waters, Hagoth-like, from the Americas, then an American Alma could have been the necessary

corrective revelation, in human form, to purify an incomplete (or misunderstood) religion of the One True God. At any rate, Melville's

investigation of Manco Capac would have led him to sundry beliefs that Peruvian god-man had actually been St. Thomas, or even Jesus

Christ (see Kingsborough) -- and Melville's further study of published LDS assertions would have led him to the Book of Mormon and to

that volume's Prophet(s) Alma, (the driving force for the establishment of alleged Nephite Christianity). The elder Alma eventually

disappears from the Book of Mormon narrative; an oddity reminiscent of Quetzalcoatl's disappearance from Mexico and Lobaska's

disappearance from Solomon Spalding's "Roman story."

That may be correct; however, Melville's Christlike character appears to be a younger and less worldly fellow, than the imperious

"Lion of the Lord." In 1857 Brigham Young was Governor of the Territory of Utah, making preparations to do battle with the Army of

the USA -- hardly a "green" religious oracle. On the other hand, the conventional account then being spread by LDS missionaries

was the miraculous story of a young (green) Joseph Smith's first vision. The beardless, newly summoned prophet of those missionary

sermons seems a better fit with Melville's word picture in The Confidence-Man. H. Bruce Franklin agrees with this

interpretation; he says on page 3

of his 1967 annotated edition: "'Green': unseasoned; Utah implies Mormons. Joseph Smith, the first Mormon Prophet...

was attacked as a vicious impostor or a witless enthusiast." After all, we should remember that Melville's character similitudes

are often subtle, obscure, multi-faceted and purposely ambiguous. It is not merely Joseph Smith who boards the steamship Fidèle,

but rather, a composite personage who embodies several different purposes and symbols.

So, if we are to believe this writer, then Herman Melville, in the

twenty-second chapter of The Confidence-Man,

"takes aim against" 1850s LDS missionaries, for being "agents of God." This sounds very much like persecution wrought

with the pen, rather than the sword. The swindling promotion of worthless city lots in Nauvoo summons up mental images

of Isaac Galland's eastern salesmanship tour, when that riverside utopia was first being built. That was not so much a

Mormon con game as it was a hustle based upon the prospect of the "New Jerusalem" making all of its share-holders rich.

As for the supposed "missionary" pointed out in Farr's paper, it is doubtful that the "man with the brass plate" is

a stand-in for a Mormon elder peddling faith in the "brass plates of Laban." Farr supposes that the LDS missionaries

of Melville's day would have been elucidating Joseph Smith's path of "eternal progression to godhood;" but that seems

highly unlikely. LDS doctrines of theosis were not typically preached to the Gentiles, along with the First Principles

of the Gospel, and Herman Melville would have been hard-pressed to have discovered even hazy published hints of the LDS

tenets associated with the "plurality of the gods," until after he had begun writing The Confidence-Man.

This brings us back to the Melville character based (at least in part) upon William Smith, whom we met previously in Chapter Eight of The Confidence-Man. Farr notices that this con man's description "suggests popular depictions of the prophet" Joseph Smith, but she fails to explain that Smith, in the 1840s and 1850s was often pictured wearing a white cravat.

An 1844 report describes the Mormon leader as:

"quite a large man, light complexion, hair and eyebrows very light, eyes prominent and blue, a remarkably receding

forehead [and] chin retreating; dresses neatly, but not peculiarly, excepting his high shirt collar and [large] white cravat..."

|

~ SECTION 6 ~ Back to Basics

If Joseph Smith, Jr. can accurately be called a 19th century confidence man, should that fact alone discourage the Latter Day Saints from

fully supporting and promoting their church? After all, Smith lived long ago and his activities as a treasure seer have been practically

forgotten by the modern members of the church he founded. Among the Christians, it might be remembered that there was a similar problem in

the early career of Saul of Tarsus -- before he became the "Apostle Paul." If Christians can forgive and selectively forget Paul's

problematic pre-baptismal affairs, could not Mormons do much the same in the case of Joseph Smith?

Detail from Bernardo Daddi's Martyrdom of St. Stephen (Paul on the left)

In Smith's telling of the story, his only transgression worthy of mention was a temporarily

frivolous attitude and his only distraction from a prophetic calling was a temporarily unsuccessful excavation of an old silver mine. In

other words, if Joe Smith began his career as a con man, he must have retained at least one aspect of a con man's deception, in telling

and re-telling his own past story. Given the fact that Smith later used deception to cover over his personal secret polygamy, the student

of Mormon history has reason to suspect his imperfect honesty in other instances as well.

If this conclusion can be cited as representing contemporary Mormon opinion, then the realizations of intellectual or spiritual inquirers

like Herman Melville might approach in wisdom those typified by the "religion-making imagination" of Joseph Smith, Jr., but only the Divine

"revelation" uttered by Smith himself can provide the explanations, truth or perfection these lesser minds seek to have communicated.

Rust thus has Melville posing "deeply probing questions" and Smith providing the "answers," inspired and facilitated by "revelation."

If this is so, then we might ask why Herman Melville did not simply affirm Joseph Smith as the great latter day prophet?

But is this the stuff of "revelation?" Where in all of this being "diffused through time and space" (Prophet Smith might demand) is

the requisite, plenary and propositional "Thus saith the Lord God of Israel...?"

Would Joseph Smith have fathomed such an ecstatic insight as "revelation?" Probably not. Smith's perspective on such matters might better be summarized in the inarticulate prose of Father Lehi in 2nd Nephi:

What prophetic elements are present in this example, but lacking in the excerpt from Melville? (1) A rigid Christian theological

framework: Even though Lehi gives voice to revelation centuries before the birth of Jesus, his oracle is replete with the Christology

of the early church. For Joseph Smith (an inveterate Bible reader and hyperliteralist), the "spirit" of prophecy and revelation

was necessarily "the testimony of Jesus." (2) Definite Divine authority: Lehi was designated the prophet of God. Although some of the

men subject to his patriarchal control (Nephi, Jacob, etc.) might also communicate revelation, all who did so were subject to his

counsel and criterion. (3) A word-for-word, unerring communication from the biblical God. (4) The requirement that any new oracle must

be compatible with all prior revelation.

Notice the sequence of events in the development of Joseph Smith's alleged religious (and temporal) authority, as reported by

Elder Robinson: (1) Mormons felt blessed to be Smith's followers and considered him "a superior personage;" (2) Mormons accepted

"revelation" communicated by Smith as God's Word; (3) In an early "revelation" God purportedly commanded Smith's followers to

"receive his (Smith's) word as from the mouth of God;" (4) Thenceforth Mormons received Smith's teachings as Divine law; (5)

The doctrines subsequently taught by Smith lowered the "vital piety, which the masses of the people were endeavoring to maintain."

Was Joseph Smith, Jr, a 19th century con man? -- a religious fraud? -- a pious fraud? If he was any of these, he possessed an "imagination"

greater than Mohammed's and perhaps greater than St. Paul's, as the American confidence-builder who "surpassed all... before or since." He

deserves a unique place in Melville's mythology. According to Martin Blythe, Melville evidently granted this 19th century

money-digger-turned-Moses just that -- a definite "place" on the mythic map. In the novel Mardi the searching voyagers come at last

to Serenia, where life is lived according to the precepts of the prophet Alma. It is the seekers' final resting place: all of them (save for

a single dissenter) embrace the one true religion and become "enthusiasts... who pretend to the unnatural conjunction of reason with things

revealed; where Alma, they say, is restored to his divine original; where... men strive to live together in gentle bonds of peace and

charity." Does Melville drop hints of suspicion with the words "pretend" and "unnatural?" Ought we to gaze a bit askance at this "charity,"

which we have encountered all too often in the parlance of Melville's many confidence men?

our petitions were treated with contempt; and in many cases the petitioner spurned from their presence, and particularly by Joseph, who would state that if he had sinned, and was guilty of the charges we would charge him with, he would not make acknowledgment, but would rather be damned; for it would detract from his dignity, and would consequently ruin and prove the overthrow of the Church. We would ask him on the other hand, if the overthrow of the Church was not inevitable, to which he often replies, that we would all go to Hell together, and convert it into a heaven, by casting the Devil out; and says he, Hell is by no means the place this world of fools suppose it to be, but on the contrary, it is quite an agreeable place; to which we would now reply, he can enjoy it if he is determined not to desist from his evil ways; but as for us, and ours, we will serve the Lord our God! |

rev. 0: July 5, 2009

OPENING NEW HORIZONS IN MORMON HISTORY