Our Moto: -- The Saints' Singularity -- is Unity, Liberty, Charity.

Vol. I. - No. 13.

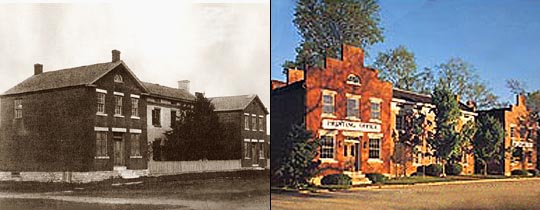

Nauvoo, Hancock Co., Wednesday, July 26, 1843.

Whole No. 65.

TRIAL OF JOSEPH SMITH.

... SIDNEY RIGDON, sworn. Says,

I arrived in Far West, Caldwell county, Missouri on the 4th of April, 1838, and enjoyed peace and quietness in common with the rest of the citizens,

until the August following, when great excitement was created by the office-seekers. Attempts were made to prevent the citizens of Caldwell [sic] from voting.

Soon after the election, which took place in the early part of August, the citizens of Caldwell were threatened with violence from those of Davis county,

and other counties adjacent to Caldwell.

This, the August of 1838, I may date as the time of the beginning of all the troubles of our people in Caldwell county, and in all the counties in the state

where our people were living. We had lived in peace from the April previous until this time, but from this time till we were all out of the state, it was one

scene of violence following another in quick succession.

There were at this time settlements in Clay, Ray, Carroll, Caldwell, and Davis counties, as well as some families living in other counties. A simultaneous

movement was made in all the counties where settlements were made in every part of the state, which soon became violent, and threatenings were heard

from every quarter. Public meetings were held and the most inflammatory speeches made, and resolutions passed which denounced all the citizens of these

counties in the most bitter and rancorous manner. These resolutions were published in the papers, and the most extensive circulation given to them that

the press of the country was capable of giving.

The first regular mob that assembled was in Carroll county, and their efforts were directed against the settlements made in that county, declaring their

determination to drive out of the county all the citizens who were of our religion, and that indiscriminately, without regard to anything else but their religion.

The only evidence necessary to dispossess any individual or family, or all the evidence required, would be that they were Mormons, as we were called,

or rather that they were of the Mormon religion. This was considered of itself crime enough to cause any individual or family to be driven from their homes,

and their property made common plunder. Resolutions to this effect were made at public meetings held for the purpose, and made public through the

papers of the state, in the face of all law, and all authority.

I will now give a history of the settlement in Carroll county. In the preceding April, as myself and family were on our way to Far West, we put up at a

house in Carroll county, on a stream called Turkey creek, to tarry for the night. Soon after we stopped, a youngerly man came riding up, who also stopped

and staid through the night. Hearing my name mentioned, he introduced himself to me as Henry Root, said he lived in that county at a little town called

De Witt, on the Missouri river, and had been at Far West, to get some of those who were coming into that place, to form a settlement at De Witt; speaking

highly of the advantages of the situation, and soliciting my interference in his behalf, to obtain a number of families to commence at that place, as he was

a large proprietor in the town plat. He offered a liberal share in all the profits which might arise from the sale of property there, to those who would aid him

in getting the place settled. In the morning we proceeded on our journey.

Some few weeks after my arrival, the said Henry Root, in company with a man by the name of David Thomas, came to Far West on the same business;

and after much solicitation on their part, it was agreed that a settlement should be made in that place; and in the July following, the first families removed

there, and the settlement soon increased, until in the October following, it consisted of some seventy families. By this time a regular mob had collected,

strongly armed, and had obtained possession of a cannon, and stationed a mile or two from the town. The citizens, being nearly all new comers, had to

live in their tents and wagons, and were exerting themselves to the uttermost to get houses for the approaching winter. The mob commenced committing

their depredations on the citizens, by not suffering them to procure the materials for building, keeping them shut up in the town, not allowing them to go

out to get provisions, driving off their cattle, and preventing the owners from going in search of them. In this way the citizens were driven to the greatest

extremities, actually suffering for food and every comfort of life, in consequence of which there was much sickness and many died. Females gave birth to

children without a house to shelter them, and in consequence of the exposure, many suffered great afflictions and many died.

Hearing of their great sufferings, a number of the men of Far West determined on going to see what was doing there. Accordingly we started, eluded the

vigilance of the mob, and notwithstanding they had sentinels placed on all the principal roads, to prevent relief from being sent to the citizens, we safely

arrived in De Witt, and found the people as above stated.

During the time we were there, every effort that could be, was made to get the authorities of the county to interfere and scatter the mob. The judge of the

circuit court was petitioned, but without success, and after that the governor of the state, who returned for answer that the citizens of De Witt had got into

a difficulty with the surrounding country, and they might get out of it; for he would have nothing to do with it, or this was the answer the messenger brought,

when he returned.

The messenger was a Mr. Caldwell, who owned a ferry on Grand river, about three miles from De Witt, and was an old settler in the place.

The citizens were completely besieged by the mob, no man was at liberty to go out, nor any to come in. The extremities to which the people were driven

were very great, suffering with much sickness, without shelter, and deprived of all aid either medical or any other kind, and being without food or the privilege

of getting it, and betrayed by every man who made the least pretension to friendship; a notable instance of which I will here give as a sample of many others

of a similar kind. There was neither bread nor flour to be had in the place; a steamboat landed there and application was made to get flour but the captain

said there was none on board. A man then offered his services to get flour for the place; knowing, he said, where there was a quantity. Money was given to

him for that purpose; he got on the boat and went off; and that was the last we heard of the man or the money. This was a man who had been frequently in

De Witt during the siege, and professed great friendship. In this time of extremity, a man who had a short time before moved into De Witt, bringing with him

a fine yoke of cattle, started out to hunt his cattle, in order to butcher them, to keep the citizens from actual starvation, but before he got but a little way from

the town, he was fired upon by the mob and narrowly escaped with his life, and had to return, or at least, such was his report when he returned. Being now

completely inclosed on every side, we could plainly see many men on the opposite side of the river, and it was supposed that they were there to prevent the

citizens from crossing, and indeed a small craft crossed from them, and three men in it, who said that that was the object for which they had assembled.

At this critical moment, with death staring us in the face, in its worst form; cut off from all communication with the surrounding country, and all our provisions

exhausted, we were sustained as the children of Israel in the desert, only by different animals. They by quails, and we by cattle and hogs which came walking

into the camp, for such it truly was, as the people were living in tents and wagons, not being privileged with building houses. What was to be done in this

extremity? why, recourse was had to the only means of subsistence left, and that was to butcher the cattle and hogs which came into the place, without

asking who was the owner, or without knowing, and what to me is remarkable is, that a sufficient number of animals came into the camp to sustain life during

the time in which the citizens were thus beseiged by the mob. This indeed was but coarse living, but such as it was, it sustained life.

From this circumstance the cry went out that the citizens of De Witt, were thieves and plunderers, and were stealing cattle and hogs. During this time the

mob of Carroll county said that all they wanted was that the citizens of De Witt should leave Carroll county and go to Caldwell and Davis counties. The citizens

finding that they must leave De Witt, or eventually starve, finally agreed to leave; and accordingly preparations were made and De Witt was vacated. The first

morning after we left, we put up for the night in a grove of timber. Soon after our arrival in the grove, a female who a short time before had given birth to a

child, in consequence of exposure, died. A grave was dug in the grove, and the next morning the body was deposited in it without a coffin, and the company

proceeded on their journey; part of them going to Davis county, and part into Caldwell: This was in the month of October, 1838.

In a short time after their arrival in Davies and Caldwell counties, messengers arrived, informing the new citizens of Caldwell and Davies, that the mob was

marching to Davies county, with their cannon with them, threatening death to the citizens, or else that they should all leave Daviess county. This caused

other efforts to be made to get the authorities to interfere. I wrote two memorials, one to the governor and one to Austin A. King, circuit judge, imploring

their assistance and intervention to protect the citizens of Davies against the threatened violence of the mob. -- These memorials were accompanied with

affidavits which could leave no doubt on the mind of the governor or judge, that the citizens before mentioned were in eminent [sic] danger. At this time things

began to assume an alarming aspect both to the citizens of Davies and Caldwell counties. Mobs were forming all around the country, declaring that they

would drive the people out of the state. This made our appeals to the authorities more deeply solicitous as the danger increased, and very soon after this

the mobs commenced their depredations; which was a general system of plunder; tearing down fences, exposing all within the field to destruction, and driving

off every animal they could find.

Sometime previous to this, in consequence of the threatenings which were made by mobs, or those who were being formed into mobs, and the abuses

committed by them on the persons and property of the citizens; an association was formed, called the Danite Band.

This, as far as I was acquainted with it, (not being myself one of the number, neither was Joseph Smith, Senior,) was for mutual protection against the bands

that were forming, and threatened to be formed; for the professed object of committing violence on the property and persons of the citizens of Davies and

Caldwell counties. They had certain signs and words by which they could know one another, either by day or night. They were bound to keep these signs

and words secret; so that no other person or persons than themselves could know them. When any of these persons were assailed by any lawless band,

he would make it known to others, who would flee to his relief at the risk of life. In this way they sought to defend each other's lives and property, but they

were strictly enjoined not to touch any person, only those who were engaged in acts of violence against the persons or property of one of their own number

or one of those whose life and property they had bound themselves to defend.

This organization was in existence when the mobs commenced their most violent attempts upon the citizens of the before mentioned counties, and from this

association arose all the horror afterwards expressed by the mob at some secret clan known as Danites.

The efforts made to get the authorities to interfere at this time was attended with some success. The militia was ordered out under the command of

Major General Atchison, of Clay county, Brigadier Generals Doniphan, of Clay, and Parks of Ray county, who marched their troops to Davies county, where

they found a large mob, and General Atchison said in my presence, that he took the following singular method to disperse them. He organized them with

his troops as part of the militia called out, to suppress and arrest the mob; after having thus organized them, he discharged them and all the rest of the

troops as having no further need for their services, and all returned home.

This, however, only seemed to give the mob more courage to increase their exertions with redoubled vigor. They boasted after that, that the authorities would

not punish them, and they would do as they pleased. In a very short time their efforts were renewed with a determination not to cease until they had driven

the citizens of Caldwell, and such of the citizens of Davies as they had marked out as victims, from the state. A man by the name of Cornelius Gillum who

resided in Clay county, and formerly sheriff of said county, organized a band, who painted themselves like Indians, and had a place of rendezvous at Hunter's

Mills on a stream called Grindstone. I think it was in Clinton county, the county west of Caldwell, and between it and the west line of the state. From this place

they would sally out and commit their depredations. Efforts were again made to get the authorities to put a stop to these renewed outrages, and again General

Doniphan and General Parks were called out with such portions of their respective brigades as they might deem necessary to suppress the mob, or rather

mobs, for by this time there were a number of them. General Doniphan came to Far West, and while there, recommended to the authorities of Caldwell to

have the militia of said county called out as a necessary measure of defence; assuring us that Gillum had a large mob on the Grindstone, and his object was

to make a descent upon Far West, burn the town and kill or disperse the inhabitants; and that it was very necessary that an effective force should be ready

to oppose him, or he would accomplish his object.

The militia was accordingly called out. He also said that there had better be a strong force sent to Davies county to guard the citizens there: he recommended that

to avoid any difficulties which might arise, they had better go in very small parties, without arms, so that no legal advantage could be taken of them. I will here

give a short account of the courts and internal affairs of Missouri, for the information of those who are not acquainted with the same.

Missouri has three courts of law peculiar to that state. The supreme court, the circuit court, and the county court. The two former, about the same as in many

other states of the Union. The county court, is composed of three judges, elected by the people of the respective counties. This court is in some respects like

the court of probate in Illinois, or the surrogate's court of New York; but the powers of this court are more extensive than the courts of Illinois or New York. The

judges, or any one of them, of the county court of Missouri, has the power of issuing habeas corpus, in all cases where arrests are made within the county where

they preside. They have also all power of justices of the peace in civil, as well as criminal cases; for instance, a warrant may be obtained from one of these

judges, by affidavit, and a person arrested under such warrant. From another of these judges, a habeas corpus may issue, and the person arrested be ordered

before him, and the character of the arrest be inquired into, and if in the opinion of the judge, the person ought not to be holden by virtue of said process, he

has power to discharge him. In the internal regulation of the affairs of Missouri, the

counties in some respects are nearly as independent of each other as the several states of the Union. No considerable number of men armed, can pass out of

one county into, or through another county, without first obtaining the permission of the judges of the county court, or some one of them, otherwise they are

liable to be arrested by the order of said judges; and if in their judgment they ought not thus to pass, they are ordered back from whence they came; and, in

case of refusal, are subject to be arrested or even shot down in case of resistance. The judges of the county court or any one of them, have the power to call

out the militia of said county upon affidavit being made to them for that purpose, by any of the citizens of said county; shewing it just, in the judgment of such

judge or judges, why said militia should be called out to defend any portion of the citizens of said county. The following is the course of procedure: Affidavit is

made before one or any number of the judges, setting forth, that the citizens of said county, or any particular portion of them, is either invaded or threatened

with invasion by some unlawful assembly whereby their liberties, lives, or property may be unlawfully taken. When such affidavit is made to any one of the judges

or all of them, it is the duty of him or them, before whom such affidavit is made, to issue an order to the sheriff of the county, to make requisition upon the

commanding officer of the militia of said county, to have immediately put under military order such a portion of the militia under his command as may be

necessary for the defence of the citizens of said county.

In this way the militia of any county may be called out at any time deemed necessary by the county judges, independently of any other civil authority of the state.

In case that the militia of the county is insufficient to quell the rioters, and secure the citizens against the invaders, then recourse can be had to the judge of

the circuit court, who has the same power over the militia of his judicial district, as the county judges have over the militia of the county. And in case of

insufficiency in the militia of the judicial district of the circuit judge, recourse can be had to the governor of the state, and all the militia of the state called out.

and if this should fail, then the governor can call on the President of the United States, and all the forces of the nation be put under arms.

I have given this expose of the internal regulation of the affairs of Missouri, in order that the court may clearly understand what I have before said on this subject,

and what I may hereafter say on it.

It was in view of this order of things that General Doniphan, who is a lawyer of some celebrity in Missouri, gave the recommendation he did at Far West, when

passing into Davies county with his troops, for the defence of the citizens of said county. It was in consequence of this, that he said, that those of Caldwell

county who went into Davies county, should go in small parties, and unarmed, in which condition they were not subject to any arrest from any authority whatever.

In obedience to these recommendations the militia of Caldwell county was called out; affidavits having been made to one of the judges of the county, setting

forth the danger which it was believed the citizens were in, from a large marauding party assembled under the command of one Cornelius Gillum, on a stream

called Grindstone. When affidavit was made to this effect, the judge issued his order to the sheriff of the county, and the sheriff to the commanding officer, who

was Colonel G. M. Hinkle, and thus were the militia of the county of Caldwell put under orders.

General Doniphan, however, instead of going into Davies county, soon after he left Far West returned to Clay county with all his troops, giving as his reason the

mutinous character of his troops, which he said would join the mob, he believed, instead of acting against them, and that he had not power to restrain them.

In a day or two afterwards, General Parks of Ray county, also came to Far West, and said that he had sent on a number of troops to Davies county to act in

concert with General Doniphan. He also made the same complaint concerning the troops, that Doniphan had, doubting greatly whether they would render

any service to those in Davies, who were threatened with violence by the mobs assembling; but on hearing that Doniphan, instead of going to Davies county,

had returned to Clay, followed his example and ordered his troops back to Ray county, and thus were the citizens of Caldwell county and those of Davies county,

who were marked out as victims by the mob, left to defend themselves the best way they could.

What I have here stated in relation to Generals Doniphan and Parks, were conversations had between myself and them, about which I cannot be mistaken,

unless my memory has betrayed me.

The militia of the county of Caldwell were now all under requisition, armed and equipped according to law. The mob after all the authority of the State had been

recalled, except from the force of Caldwell county, commenced the work of destruction in earnest; showing a determination to accomplish their object. Far West,

where I resided, which was the shire town of Caldwell county, was placed under the charge of a captain by the name of Killian, who made my house his head

quarters; other portions of the troops were distributed in different places in the county, wherever danger was apprehended. In consequence of Captain Killians'

making any house his head quarters, I was put in possession of all that was going on, as all intelligence in relation to the operations of the mob was

communicated to him. Intelligence was received daily of depredations being committed not only against the property of the citizens, but other [sic - their?]

persons; many of whom when attending to their business, would be surprised, and taken by marauding parties, tied up and whipped in a most desperate

manner. Such outrages were common during the progress of these extraordinary scenes, and all kinds of depredations were committed. Men driving their

teams to and from the mills where they got their grinding done, would be surprised and taken, their persons abused, and their teams, wagons and loading

all taken as booty by the plunderers. Fields were thrown open, and all within exposed to the destruction of such animals as chose to enter. Cattle, horses,

hogs and sheep were driven off, and a general system of plunder and destruction of all kinds of property, carried on to the great annoyance of the citizens

of Caldwell, and that portion of the citizens of Davies marked as victims by the mob. One afternoon a messenger arrived at Far West calling for help, saying

that a banditti had crossed the south line of Caldwell, and were engaged in threatening the citizens with death if they did not leave their homes and go out

of the state within a very short time; the time not precisely recollected; but I think it was the next day by ten o'clock, but of this I am not certain. He said they

were setting fire to the prairies, in view of burning houses and desolating farms, that they had set fire to a wagon loaded with goods, and they were all

consumed; that they had also set fire to a house, and when he left it was burning down. Such was the situation of affairs at Far West at that time, that Captain

Killian could not spare any of his forces, as an attack was hourly expected at Far West. The messenger went off, and I heard no more about it, till some time

the night following, when I was awakened from sleep by the voice of some man apparently giving command to a military body; being somewhat unwell, I did

not get up. Some time after I got up in the morning, the sheriff of the county stopped at the door, and said that David Patten, had had a battle with the mob

last night at crooked river, and that several were killed and a number wounded; that Patten was among the number of the wounded, and his wound supposed

to be mortal. After I had taken breakfast another gentleman called, giving me the same account, and asking me if I would not take my horse and ride out with

him and see what was done. I agreed to do so, and we started, and after going three or four miles, met a company coming into Far West. We turned and went

back with them.

This mob proved to be that headed by the Reverend Samuel Bogard, a Methodist preacher, and the battle was called the Bogard Battle. After this battle there

was a short season of quiet, the mobs disappeared, and the militia returned to Far West, though they were not discharged, but remained under orders until it

should be known how the matter would turn. In the space of a few days, it was said that a large body of armed men were entering the south part of Caldwell

County. The county court ordered the militia to go and enquire what was their object, in thus coming into the county without permission. The military started as

commanded, and little or no information was received at Far West about their movements until late the next afternoon, when a large army was descried making

their way towards Far West. Far West being an elevated situation, the army was discovered while a number of miles from the place. Their object was entirely

unknown to the citizens as far as I had any knowledge on the subject, and every man I heard speak of their object, expressed as great ignorance as myself. --

They reached a small stream on the east [sic south?] side of the town, which was studded with timber on its banks, and for perhaps from half a mile to a mile

on the east [sic - south?] side of the stream, an hour before sundown. There the main body halted, and soon after a detachment under the command of

Brigadier General Doniphan, marched towards the town in line of battle. This body was preceded, probably three fourths of a mile in advance of them, by a man

carrying a white flag, who approached within a few rods of the eastern boundary of the town, and demanded three persons, who were in the town, to be sent to

their camp, after which the whole town, he said, would be massacred. When the persons who were inquired for, were informed, they refused to go, determined

to share the common fate of the citizens. One of those persons did nor belong to the "Church of Latter Day Saints." His name is Adam Lightner, a merchant

in that city.

The white flag returned to the camp. To the force of General Doniphan, was the small force of Caldwell militia, under Colonel Hinkle, opposed. Who also marched

in line of battle to the eastern [sic - southern?] line of the town. The whole force of Colonel Hinkle did not exceed three hundred men -- that of Doniphan perhaps

three times that number. I was in no way connected with the militia, being over age, neither was Joseph Smith, Senior. I went into the line formed by Colonel

Hinkle though unarmed, and stood among the rest to await the result, and had a full view of both forces, and stood there. The armies were within rifle shot of

each other. About the setting of the sun Doniphan ordered his army to return to the camp at the Creek: they wheeled and marched off. After they had retired,

it was consulted what was best to do -- by what authority the army was there no one could tell, as far as I knew -- it was agreed to build through the night a

sort of fortification, and if we must fight, sell our lives as dear as we could; accordingly all hands went to work, rails, house-logs, and wagons, were all put in

requisition: and the east [sic - south?] line of the town as well secured as could be done by the men and means, and the short time allowed; expecting an

attack in the morning. The morning at length came, and that day passed away and still nothing was done; but plundering the cornfields, shooting cattle and

hogs, stealing horses and robbing houses, and carrying off potatoes, turnips, and all such things as the army of General Lucas could get, for such in the

event they proved to be. The main body being commanded by Samuel D. Lucas, a Deacon in the Presbyterian church. The next day came and then it was

ascertained that they were there by order of the Governor.

A demand was made for Joseph Smith, Senior, Lyman Wight, George W. Robinson, Parley P. Pratt and myself, to go into their camp; with this command we

instantly complied, and accordingly started to their camp. When we came in sight of their camp the whole army was on parade, marching toward the town,

we approached and met them; and were informed by Lucas that we were prisoners of war. A scene followed that would defy any mortal to describe, a howling

was set up, that would put any thing I ever heard before or since at defiance. I thought at the time it had no parallel except it might be the perdition of ungodly

men. They had a cannon. I could distinctly hear the guns as the locks were sprung, which appeared, from the sound to be in every part of the army. General

Doniphan came riding up where we were, and swore by his maker that he would hew the first man down that cocked a gun, one or two other officers on

horseback also rode up, ordering those who had cocked their guns to uncock them, or they would be hewed down with their swords, we ware conducted into

their camp and made to lay on the ground through the night.

This was late in October -- we were kept here for two days and two nights. It commenced raining and snowing until we were completely drenched and being

compelled to lay on the ground, which had became very wet and the water was running round us and under us -- what consultation the officers and others had

in relation to the disposition that was to be made of us, I am entirely indebted to the report made to me by General Doniphan as none of us was put on any

trial. General Doniphan gave an account of which the following is the substance, as far as my memory serves me: "That they held a Court Martial and sentenced

us to be shot at 8 o'clock the next morning after the Court Martial was holden, in the public square in the presence of our families -- that this Court Martial was

composed of seventeen preachers and some of the principal officers of the army -- Samuel D. Lucas presided -- Doniphan arose and said 'that neither himself

nor his brigade should have any hand in the shooting, that it was nothing short of cold blooded murder' and left the Court Martial and ordered his brigade to

prepare and march off the ground."

This was probably the reason why they did not carry the decision of the Court Martial into effect. It was finally agreed that we should be carried into Jackson

county, accordingly on the third day after our arrest the army was all paraded, we were put into waggons and taken into the town -- our families having heard

that we were to be brought to town that morning to be shot. When we arrived a scene ensued such as might be expected under the circumstances. I was

permitted to go alone with my family into the house, there I found my family so completely plundered of all kinds of food that they had nothing to eat but

parched corn which they ground with a hand mill, and thus were they sustaining life. I soon pacified my family and allayed their feelings by assuring them

that the ruffians dared not kill me. I gave them strong assurances that they dared not do it, and that I would return to them again. After this interview I took

my leave of them, and returned to the waggon, got in and we were all started off for Jackson county. Before we reached the Missouri river a man came riding

along the line apparently in great haste. I did not know his business. When we got to the river Lucas came to me and told me that he wanted us to hurry,

as Jacob Stollings had arrived from Far West with a message from Gen. John C. Clark, ordering him to return with us to Far West as he was there with a

large army, he said he would not comply with the demand, but did not know but Clark might send an army to take us by force. We were hurried over the river

as fast as possible with as many of Lucas' army as could be sent over at one time and sent hastily on, and thus we were taken to Independence, the Shire

town of Jackson county, and put into an old house and a strong guard placed over us. In a day or two they relaxed their severity, we were taken to the best

tavern in town and there boarded, and treated with kindness -- we were permitted to go and come at our pleasure without any guard. After some days Colonel

Sterling G. Price arrived from Clark's army with a demand to have us taken to Richmond, Ray county. It was difficult to get a guard to go with us, indeed, we

solicited them to send one with us, and finally got a few men to go and we started; after we had crossed the Missouri, on our way to Richmond, we met a

number of very rough looking fellows, and as rough acting as they were looking, they threatened our lives. -- We solicited our guard to send to Richmond for

a stronger force to guard us there, as we considered our lives in danger. Sterling G. Price met us with a strong force and conducted us to Richmond where we

were put in close confinement.

One thing I will here mention, which I forgot -- while we were at Independence I was introduced to Russell Hicks, a lawyer of some note in the country. In

speaking on the subject of our arrest and being torn from our families, [he] said he presumed it was another Jackson county scrape. He said the Mormons

had been driven from that county and that without any offence on their part. He said he knew all about it, they were driven off because the people feared their

political influence. And what was said about the Mormons was only to justify the mob in the eyes of the world for the course they had taken. He said this

was another scrape of the same kind.

This Russell Hicks, by his own confession, was one of the principal leaders in the Jackson county mob.

After this digression, I will return -- The same day that we arrived at Richmond, Price came into the place where we were, with a number of armed men, who

immediately on entering the room cocked their guns, another followed with chains in his hands, and we were ordered to be chained together -- a strong guard

was placed in and around the house, and thus we were secured. The next day General Clark came in, and we were introduced to him -- the awkward manner

in which he entered and his apparent embarrassment were such as to force a smile from me. He was then asked for what he had thus cast us into prison? --

to this question he could not or did not give a direct answer. He said he would let us know in a few days, and after a few more awkward and uncouth movements

he withdrew. After he went out I asked some of the guard what was the matter with General Clark, that made him appear so ridiculous? They said he was

near sighted. I replied that I was mistaken if he were not as near witted as he was near sighted.

We were now left with our guards, without knowing for what we had been arrested, as no civil process had issued against us -- for what followed until General

Clark came in again to tell us that we were to be delivered into the hands of the civil authorities, I am entirely indebted to what I heard the guards say -- I heard

them say that General Clark had promised them before leaving Coles county, that they should have the privilege of shooting Joseph Smith, Senior and myself.

And that General Clark was engaged in searching the military law to find authority for so doing; but found it difficult as we were not military men and did not

belong to the militia; but he had sent to Fort Leavenworth for the military code of law, and he expected, after he got the laws, to find law to justify him in

shooting us.

I must here again digress, to relate a circumstance which I forgot in its place. I had heard that Clark had given a military order to some persons who had

applied to him for it, to go to our houses and take such goods as they claimed. The goods claimed, were goods sold by the sheriff of Caldwell county on an

execution, which I had purchased at the sale. The man against whom the execution was issued, availed himself of that time of trouble to go and take the

goods wherever he could find them. -- I asked Clark if he had given any such authority. He said that an application had been made to him for such an order,

but he said, "your lady wrote me a letter requesting me not to do it -- telling me that the goods had been purchased at the sheriff's sale; and I would not

grant the order." I did not, at the time, suppose that Clark, in this, had barefacedly lied; but the sequel proved he had -- for, some time afterwards, behold

there comes a man to Richmond with the order, and shewed it to me, signed by Clark. The man said he had been at our house, and taken all the goods he

could find. So much for a lawyer, a Methodist, and a very pious man at that time in religion, and a major general of Missouri.

During the time that Clark was examining the military law, there were something took place which may be proper to relate in this place. I heard a plan laying

among a number of those who belonged to Clark's army, and some of them officers of high rank, to go to Far West and commit violence on the persons of

Joseph Smith Senior's wife and my wife and daughter.

This gave me some uneasiness. I got an opportunity to send my family word of their design, and to make such arrangements as they could to guard against

their vile purpose. The time at last arrived, and the party started for Far West. I waited with painful anxiety for their return. After a number of days, they returned.

I listened to all they said, to find out, if possible, what they had done. One night, I think the very night after their return, I heard them relating to some of those

who had not been with them the events of their adventure. Inquiry was made about their success in the particular object of their visit to Far West. The substance

of what they said in answer, was, "that they had passed and repassed both houses, and saw the females, but there were so many men about the town, that

they dare not venture for fear of being detected, and their numbers were not sufficient to accomplish anything, if they made the attempt, and they came off

without trying."

No civil process of any kind had been issued against us: we were then held in duress without knowing what for, or what charges were to be preferred against us.

At last, after long suspense, General Clark came into the prison, presenting himself about as awkwardly as at the first, and informed us, "that we would be put

into the hands of the civil authorities. He said he did not know precisely what crimes would be charged against us, but they would be within the range of treason,

murder, burglary, arson, larceny, theft, and stealing." Here, again another smile was forced, and I could not refrain, at the expense of this would-be great man,

in whom, he said, "the faith of Missouri was pledged." After long and awful suspense, the notable Austin A. King, judge of the circuit court, took the seat, and

we were ordered before him for trial, Thomas Birch, Esq., prosecuting attorney. All things being arranged, the trial opened. No papers were read to us, no

charges of any kind preferred, nor did we know against what we had to plead. Our crimes had yet to be found out.

At the commencement we requested that we might be tried separately; but this was refused, and we were all put on our trial together. Witnesses appeared,

and the swearing commenced. It was so plainly manifested by the judge that he wanted the witnesses to prove us guilty of treason, that no person could

avoid seeing it. The same feelings were also visible in the States' Attorney. Judge King made an observation something to this effect, as he was giving directions

to the scribe, who was employed to write down the testimony -- "that he wanted all the testimony directed to certain points" -- Being taken sick at an early

stage of the trial, I had not the opportunity of hearing but a small part of the testimony when it was delivered before the court.

During the progress of the trial, after the adjournment of the court in the evening, our lawyers would come into the prison, and there the matters would be

talked over.

The propriety of our sending for witnesses was also discussed. Our attornies said that they would recommend us not to introduce any evidence at that trial.

Doniphan said it would avail us nothing, for the judge would put us in prison, if a cohort of angels were to come and swear we were innocent; and beside that,

he said that if we were to give the court the names of our witnesses, there was a band there ready to go, and they would go and drive them out of the country,

or arrest them and have them cast into prison, to prevent them from swearing, or else kill them. It was finally concluded to let the matter be so for the present.

During the progress of the trial, and while I was lying sick in prison, I had an opportunity of hearing a great deal said by those who would come in. The subject

was the all absorbing one. I heard them say that we must be put to death -- that the character of the State required it. The State must justify herself in the

course she had taken, and nothing but punishing us with death, could save the credit of the State; and it must therefore be done.

I heard a party of them one night, telling about some female whose person they had violated, and this language was used by one of them: "The damned bitch,

how she yelled." Who this person was, I did not know; but before I got out of prison, I heard that a widow, whose husband had died some few months before,

with consumption, had been brutally violated by a gang of them, and died in their hands, leaving three little children, in whose presence the scene of brutality

took place.

After I got out of prison, and had arrived in Quincy Illinois, I met a strange man in the street, who inquired of me respecting a circumstance of this kind -- saying

that he had heard of it, and was on his way going to Missouri to get the children if he could find them. He said the woman thus murdered was his sister, or

his wife's sister, I am not positive which. The man was in great agitation. What success he had I know not.

The trial at last ended, and Lyman Wight, Joseph Smith, Senior, Hyrum Smith, Caleb Baldwin, Alexander McRae, and myself were sent to jail in the village

of Liberty, Clay county, Missouri.

We were kept there from three to four months; after which time we were brought out on habeas corpus before one of the county judges. During the hearing under

the habeas corpus, I had, for the first time, an opportunity of hearing the evidence, as it was all written and read before the court.

It appeared from the evidence, that they attempted to prove us guilty of treason in consequence of the militia of Caldwell county being under arms at the time

that General Lucas' army came to Far West. This calling out of the militia, was what they founded the charge of treason upon -- an account of which I have given

above. The charge of murder was founded on the fact, that a man of their number, they said, had been killed in the Bogard battle.

The other charges were founded on things which took place in Davies. As I was not in Davies county at that time, I cannot testify anything about them.

A few words about this written testimony.

I do not now recollect one single point about which testimony was given, with which I was acquainted, but was misrepresented, nor one solitary witness whose

testimony was there written, that did not swear falsely; and in many instances I cannot see how it could avoid being intentional on the part of those who

testified -- for all of them did swear to things that I am satisfied they knew to be false at the time -- and it would be hard to persuade me to the contrary.

There were things there said, so utterly without foundation in truth -- so much so -- that the persons swearing, must at the time of swearing, have known it. The

best construction I can ever put upon it, is, that they swore things to be true which they did not know to be so, and this, to me, is wilful perjury.

This trial lasted for a long time, the result of which was that I was ordered to be discharged from prison, and the rest remanded back; but I was told by those

who professed to be my friends, that it would not do for me to go out of jail at that time, as the mob were watching, and would most certainly take my life --

and when I got out, that I must leave the State, for the mob, availing themselves of the exterminating order of Governor Boggs, would, if I were found in the State,

surely take my life -- that I had no way to escape them but to flee with all speed from the State. It was some ten days after this before I dared leave the jail.

At last, the evening came in which I was to leave the jail. Every preparation was made that could be made for my escape. There was a carriage ready to take

me in and carry me off with all speed. A pilot was ready -- one who was well acquainted with the country -- to pilot me through the country, so that I might not

go on any of the public roads. My wife came to the jail to accompany me, of whose society I had been deprived for four months. Just at dark, the sheriff and

jailer came to the jail with our supper. I sat down and ate. There were a number watching. After I had supped, I whispered to the jailer to blow out all the candles

but one, and step away from the door with that one. All this was done. The sheriff then took me by the arm, and an apparent scuffle ensued, -- so much so,

that those who were watching, did not know who it was the sheriff was scuffling with. The sheriff kept pushing me towards the door, and I apparently resisting,

until we reached the door, which was quickly opened and we both reached the street. He took me by the hand and bade me farewell, telling me to make my

escape, which I did with all possible speed. The night was dark. After I had gone probably one hundred rods, I heard some person coming after me in haste.

The thought struck me in a moment that the mob was after me. I drew a pistol and cocked it, determined not to be taken alive. When the person approaching

me spoke, I knew his voice, and he speedily came to me. In a few moments I heard a horse coming. I again sprung my pistol cock. Again a voice saluted my

ears that I was acquainted with. The man came speedily up and said he had come to pilot me through the country. I now recollected I had left my wife in the jail.

I mentioned it to them, and one of them returned, and the other and myself pursued our journey as swiftly as we could. After I had gone about three miles, my

wife overtook me in a carriage, into which I got, and we rode all night. It was an open carriage, and in the month of February, 1839. We got to the house of an

acquaintance just as day appeared. There I put up until the next morning, when I started again and reached a place called Tenney's Grove; and, to my great

surprise, I here found my family, sad was again united with them, after an absence of four months, under the most painful circumstances. From thence I made

my way to Illinois, where I now am. My wife, after I left her, went directly to Far West and got the family under way, and all unexpectedly met at Tenney's Grove.

SIDNEY RIGDON.

After hearing the foregoing evidence in support of said Petition -- it is ordered and considered by the Court, that the said Joseph Smith, Senior, be

discharged from the said arrest and imprisonment complained of in said Petition, and that the said Smith be discharged for want of substance in the

warrant, upon which he was arrested, as well as upon the merits of said case, and that he go hence without day.

[L. S.] In testimony whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and affixed the seal of said Court, at the city of Nauvoo, this 2d day of July, 1843.

JAMES SLOAN, Clerk.

Note 1: Sidney Rigdon's published testimony of July 2, 1843, in the Joseph Smith case at Nauvoo, is strangely devoid of mention of any significant

duties and powers he possessed, as a member of the Church's First Presidency in Missouri. Even more striking is Rigdon's failure to testify to the

role played by Joseph Smith at Far West in 1838. An uninformed reader of Rigdon's statement could be forgiven for picturing Smith as a disinterested,

detached religious hermit, who had no particular interest or influence in the Mormon theocracy of those times.

Note 2: Had President Rigdon wished to better refresh his memory, regarding the charges and testimony facing him during his last months in Missouri,

he might have taken the trouble to consult the 1841 pamphlet Document

Containing the Correspondence, Orders, &c. In Relation to the Disturbances with the Mormons. His store of Mormon War anecdotes might also

have been entertainingly supplemented with quotes taken from the 1841 booklet

Document Showing The Testimony... on the Trial of Joseph Smith, jr. Best of all, Rigdon could have enhanced his own ecclesiastical stature by

citing passages in the Mormon Church's 1838 tract Oration Delivered by Mr. S. Rigdon.

He chose instead to recall vague, largely undated and undocumented, fragments from his shadowy memory -- as testimony well suited to the policies

and practices of a Nauvoo court room.

|