Mormon Classics | Spalding Library | Bookshelf | Newspapers | History Vault

Sidney Rigdon,

The Real Founder of Mormonism

by:

William H. Whitsitt

BOOK THE SECOND:

BAPTIST PERIOD: June 1, 1817 - Oct. 11, 1823

(Sections I & II, pp. 007-148)

Contents | Book I | Book II: 1 2 | Book III | Book IV | Book V

"Wm. Whitsitt: Insights into Early Mormonism" | Times & Seasons' Rigdon History

D. Benedict's 1813 History of the Baptists | The Christian Baptist

|

Both these churches were founded under the labors of the Rev. John Sutton (Benedict vol. I:595). Mr. Sutton, who is believed to have been a native of New Jersey, received his education at the famous academy that was kept by the Rev. Isaac Eaten at Hopewell, New Jersey from 1750 to 1767 (Benedict II:449) and then appears for a brief season in the character of an itinerant minister in Nova Scotia. Shortly before the year 1770 he is found at Providence, Rhode Island, where in keeping with a widely publicized policy of some of the leading members of the General Baptist church of that place, to convert it into a Particular Baptist church, he was engaged as an assistant of the General Baptist pastor, the Rev. Samuel Winsor. Their relation did not long subsist; the General Baptist element are supposed to have been still vigorous enough to combine against Mr. Sutton and to (get quit of him) at the close of a six month engagement (Benedict I:479). On being released from his position at Providence, Mr. Sutton next made his way southward to the Jerseys (Benedict I:479), whence he shortly afterwards drifted into Western Penn. (Benedict I:598) and laid the foundation of the Redstone fraternity. Towards the close of his life he appears in Kentucky, and takes a part in the Emancipation movement that for a season was rife among the Baptists of that State (Benedict II:516.fn.). The Rev. John Corbley, a native of Ireland, who had been brought into the Baptist church under the ministrations of the Rev. James Ireland in Virginia, was also a partaker with Mr. Sutton in these early labors in Western Pennsylvania (Benedict I:598). It will be apparent from the above historical survey, that Baptist views must have become familiar to the people of this section of the country, by the time that Sidney Rigdon came upon the scene of action. The church at Peter's Creek had continued to enjoy a measure of prosperity under the oversight of the Rev. David Phillips, a native of Wales, who removing to this country in his childhood, had resided in Chester county, Penn. until he attained middle life when he went to reside on Peter's Creek in Allegheny county, and took charge of the church (Benedict I:601). The Redstone Association, which at this time embraced a considerable area of territory, was of "Regular Baptist" affinities, adhering to the Philadelphia Confession of Faith, and displaying small sympathy for those who in the contemporary parlance of the denomination, were designated "Separate Baptists." In the year 1809 the number of churches belonging to it is given as 33, of which the greater portion were in Pennsylvania, though a few were from Virginia and several from Ohio (Benedict I:516). Seven years later, in the year 1816, there were 32 names on the list of churches, two of which had only recently entered the organization. The First Baptist Church in Pittsburgh, which had been organized in 1812, is set down among the rest with only 8 members. Sidney Rigdon was destined to assume the pastoral care of that small interest, then grown to larger dimensions, in January, 1822. The Brush Run church, under Alexander Campbell, had sought and gained entrance to the Association in the year 1813 (Rich., Memoirs of A. Campbell, Phila., 1868, vol. I:438). It is found in the catalogue of the year 1816 and credited with 23 communicants (Richardson, v. I:469-70). Mr. Philips, who presided at Peter's Creek church, was now well advanced in years. So highly were his virtues in esteem that he was called "Father Philips" through out the country-side. A fair proportion of respectable and, for that community, influential people were found among his parishioners. The Estep family were in good repute, as also the McCrearys. The Rigdons, who for reasons already suggested were possibly in their turn included among his constituents are believed to have occupied a decent social position.

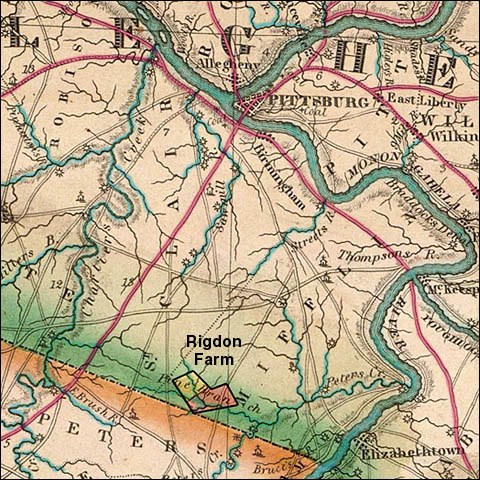

360 acre Wm. Rigdon farm on Piney Fork, in the S. W. corner of Mifflin twp. The map is from 1826, just after Sidney sold his inheritance (yellow portion) View Rigdon property location transposed to 1876 area map

Chapter II.

this time, or whether the accession of Sidney was in consequence of the ordinary ministrations of the pastor. Revival occasions were not in the least uncommon in the various religious communities of that portion of the country, and it is possible that in connection with one of these he was induced to embrace religion. The intensity of his experience of religious truth would appear to favor the conclusion suggested. It was intimated, and perhaps Rigdon himself believed, that there was an extraordinary process in his case. Indeed there was such a prominent display of what were conceived to be the miraculous features of his conversion that it is claimed the suspicions of his pastor were excited and "serious doubts were entertained in regard to the genuineness of the work" (Patterson, p. 13). Whether the suspicions of Mr. Philips were communicated to the church, or rested quietly in his own bosom, is a point that has not been made clear. It is, however most likely that these were never publicly mooted until afterwards, when the object of them had for other reasons become unwelcome to his pastor and to the congregation. It is every way worth while to take account of the intensity of this earliest religious demonstration on the part of Rigdon. It supplies an explanation of his character, and an index to much of his subsequent conduct. He was capable of the most extreme paroxysms of religious fervor, in the progress of which his bearing was highly singular, if not offensive. On the other hand his zeal was not commonly steady and continuous. If it had possessed this quality in addition, there can be small question that it would have speedily consumed his health and closed his life. His native inertia -- what his neighbors plumply denounced as "laziness" -- could always be relied upon to appear for the relief of his too highly strained faculties.

Chapter III.

it is frequently undertaken by persons who possess no suitable qualifications for the task. Certainly, those who assumed to put forward Mr. Rigdon could not have been distinguished as judicious counselors. On the other hand it must be remembered that Sidney required a very trivial amount of encouragement. He was of a temper that may fairly be stated irrepressible. There was perhaps, no authority and no power in the constitution of a Baptist church that would have availed to keep him quiet. The suspicions of the venerable pastor, however, had likely by this time become so decided as to affect the plans and wishes of the ardent young convert. It is customary for the church which he chances to be a communicant to issue a person in Rigdon's position a license to "exercise his gifts" in the gospel; but this formality seems to have been neglected in the present instance. There is no record of his obtaining any license from his brethren at Peter's Creek. Even if he had applied for such a favor in that quarter, it is possible that the request would have been denied (Patterson, pp. 9 & 3). It could not have been a great while after Rigdon commenced to exercise his capacities for public address before he conceived the project of supplanting Mr. Philips in the pastoral charge of the church. Under the circumstances this would appear to have been a very serious enterprise, but the burning zeal and the impassioned preaching of the younger man were of a style to captivate the fancy of a considerable portion of the community, and he was not far from carrying his point. The taste for ascendancy was likewise one of his most clearly pronounced peculiarities. It will often come to view in the subsequent portions of his history. The friends of Mr. Philips, while they might not have been so numerous as those who applauded the effort of Rigdon, were of superior influence and standing. These were speedily allied to the support of their long tried spiritual guide, and the intruder was put to flight (Patterson, p. 13). The occurrences hitherto described bring down our narrative as far as the winter of 1818-19. Having been defeated in his attack against the position and the peace of his pastor, Rigdon now decides that it will no longer be agreeable to his feelings to keep his residence in the vicinity of Peter's Creek. [012]

With this plan in view he resorted to the instructions of the Rev. Mr. Clark, a Baptist minister of the adjoining county of Beaver, (Patterson, p. 3). This gentleman was (considered) one of the leading preachers of the Beaver Association of Baptists, a body which had been constituted in the year 1809 (Benedict, History the Baptists, N.Y. 1856 ?, p. 618), of churches that were situated partly in the state of Pennsylvania and partly in Ohio. In Pennsylvania its boundaries embraced the counties of Beaver, Mercer and Butler. It was near the approach of winter when he made his entry into Beaver county, where it is likely that he was received as an inmate of the family of his preceptor (Patterson, p. 9). His studious mood was of brief duration, hardly as long as the winter of 1818-19. The amount of advantage he obtained from it must have been small in every other respect except in the access of conceit, a commodity of which Sidney already possessed a sufficient store. The spring of 1814 finds him at Sharon, Mercer county, where the Baptist church was under the pastoral care of Rev. Thomas G. Jones. Here he succeeds in obtaining a license to enter upon the work of the ministry (Patterson, pp. 8-9). Joseph Smith affirms that the license was issued in March, 1819 (Tullidge, p. 102). From this point it was an easy matter for him to drift across the line of Pennsylvania into the State of Ohio. During the month of May, 1819 he appears at Warren the county seat of Trumbull county in the latter state (Tullidge, Life of Joseph Smith, Plano Illinois, 1880, p. 102). [014]

Accordingly in the early summer of 1819 Sidney goes to try his fortune in Ohio. In Warren, where was one of the churches of the Beaver Association, he would naturally be accorded a kindly welcome. The church bore the name of Concord (Hayden, p. 25) and was presided over by the well known Adamson Bentley, with whom as a leader of Baptist interests in that part of the world (and as a native of his own county of Allegheny in Penn.) he would enjoy a measure of acquaintance. His services were probably in good request, since he was an orator of the Boanerges type; it is possible that means were taken to have it known that he was fresh from a course of lucubrations in theology. In his newly attained capacity as an expert in theology he would be welcome to Adamson Bentley, who had induced the preachers of the various Baptist churches in that section of the country to unite in holding annually a minister's meeting, for the purpose of conversing upon the scriptures and their own religious progress, and for mutual improvement by criticisms upon each others' sermons (Richardson II:44). The intimacy which by this means arose between the couple was soon to ripen into a more important result. Bentley, who resided in Warren since 1810, where he was also engaged in mercantile pursuits (Richardson I:217), had married there a daughter of a prominent citizen named Richard Brooks, a member of the Baptist church, whose house was always open to the preachers (Hayden pp. 95-6). His wife had a sister who was just then in the bloom of her beauty and loveliness. Miss Phoebe Brooks was born on the 3rd of May 1800 (Rigdon family Bible), and was in every sense a person of weight and worth of character. Esteeming Mr. Rigdon as a prodigy of learning and eloquence and satisfied both from an extended acquaintance with his cousin, the Rev. Thomas Rigdon, who was pastor of the New Lisbon church which was at that time connected with the Beaver Association, and from his own early knowledge of them in Allegheny county, Pennsylvania, that the Rigdon family was of good report, he probably conceived the notion of trying to secure the future happiness of his beautiful sister-in-law by bringing about her marriage with the engaging visitor from his own former home. Sidney lingered very contentedly among his friends in the vicinity of Warren, where he had easily assumed a leading position in the pulpit and was far and near esteemed and admired. During the progress of the winter of 1819-20, in the rush of his other engagements, he was at pains to cultivate the affections of Miss Brooks. This occupation was in no sense irksome, and perhaps with the countenance and the councils of Bentley, it was also not expressly difficult. The spring found him far on the way to success. On Monday the 12th of June, 1820 the day of his triumph dawned, and he was permitted to call Miss Phoebe his bride (Rigdon family Bible). The circumstance that the nuptials were celebrated on Monday, a day that is not usually chosen for festivities of this kind, might give rise to the conjecture that Mr. Brooks could not be persuaded to give his consent to the step that his daughter was taking, and that the couple were thereby constrained to resort to the expedient of an elopement. However that may be, Mr. Bentley, who it is possible was privy to the proceedings, and may have performed the ceremony, was on good terms with his new brother-in-law, and apparently full of lively hopes that success would attend the path of the wedded pair. It was perhaps a piece of good fortune for Mr. Bentley that he was in a situation to confer upon Mr. Rigdon such binding obligations. Otherwise his consuming passion for conflict and ascendancy might have given as serious annoyance to the pastor of Concord church in Warren as they had recently brought to the venerable Welshman who had been so long established at Peter's Creek. Rigdon's vulgar penchant to try conclusions with any person who might be the least in his way was one of the prominent features of his life, his vanity often consumed his peace. To his thinking the honors of supremacy and control belonged of right to his own merits. It was likewise a happy circumstance that Mr. Bentley or some other person was skillful to excite his interest for the struggles of an infant church which had been organized in the township of Bazetta, within the limits of Trumbull county, on the 22nd of January 1820. (Hayden, History of the Disciples on the Western Reserve, Cincinnati, 1876, p. 281). On the 4th of March, 1820 Rigdon was received into membership at Bazetta (Hayden, p. 93), possibly by this act transferring his membership from the church of Bentley in Warren. If his residence was at the same time established in the vicinity of the Bazetta church he would be further removed from opportunities for intrigue. Hayden states in addition that he was licensed to preach at Bazetta on the 1st of April, 1820. It is possible a stricter examination might show that this was the date and place of Sidney's ordination to the full work of the ministry. The authority on which Patterson, as cited above, assigns the event of his licensure to Sharon, in Pennsylvania, would appear to be reasonably trustworthy.

Chapter VI.

(Rich., II:34). in the early part of the year 1821 (Hayden, p. 21). At this period the sentiment of the opposition between different religious denominations was not so decided as it has now become. There was a comfortable extent of Christian union, which later events have availed to reduce to a far narrower compass consequently, the breach of Christian union which was implied and also occasioned by the public encounter of these two champions was the topic of remark in many quarters. At present, when public debates are a part of the established order in many sections of the country, a transaction like that at Mount Pleasant would scarcely be observed beyond the narrow limits of the community where it might befall. It would only be regarded in the light of another addition to an almost endless series of battles, which as they (are) being waged almost every day, do not require to be noted in detail. The debate between Campbell and Walker, however, was not in this way neglected. It was something new and sensational. Tidings concerning it were heralded to every corner of the adjacent States, and the details of it were devoured with eagerness. Mr. Campbell's book had scarcely left the press when it fell into the hands of Adamson Bentley at Warren. He was delighted with its defense of the biblical origin of the rite of immersion, and was greatly drawn towards the author of it. Doubtless Mr. Rigdon was equally attracted by the ability of this champion of an ancient and honored observance, and may have perused the debate with the same degree of interest as Bentley had displayed. The latter, having heard of the tribulations of Mr. Campbell, in the Redstone Baptist Association of which he was a member, resolved to make him a visit at the earliest opportunity, to express his thanks for what he had accomplished and to give him cheer in the trials to which he was exposed (Rich., II:44). It was natural that the youthful and ardent Rigdon should sympathize with the more experienced pastor of the Warren church in this purpose, and that he should desire to be of the party on the pilgrimage to Bethany, the home of the newly risen light. But before the printed records of the Mount Pleasant debate could be given to the public, there was an important change in the posture of Baptist interests in which Rigdon must have borne a leading part. The ministers' meeting whose direction was chiefly in the hands of Adamson Bentley, was regularly held in the month of June of each year (Hayden p. 39). It is possible that the nuptials of Sidney and Miss Brooks were performed in connection with its session in the month of June 1820. In this same meeting a resolution was passed which shortly resulted in the separation from the Beaver association of all the churches which had their seats in the State of Ohio. The body agreed that these churches should write to form an association of their own on the 30th day of August, 1820. The project was duly effected, and at the date suggested the Mahoning Association was brought into existence. Here Adamson Bentley would be the prevailing influence, but Rigdon stood only next below him being recognized as "the great orator of the Mahoning Association" (Rich., II:45). It was much in vogue at that period for Baptist ministers and those of other denominations also to go upon lengthy evangelizing at their own charges, which were commonly very slight, since the people to whom they chanced to preach were glad to supply their wants and bring them on their journey. After organizing the Mahoning Association in August 1820, Bentley and Rigdon set themselves to plan a progress of this kind. They were not able to carry out their wishes, however, until the Spring of 1821, at which date they made a lengthy circuit, passing quite across the State of Ohio, probably touching at Cincinnati, and also entering the State of Kentucky. As they were returning from this protracted visit they resolved to embrace an occasion they had sometime desired to make the acquaintance of Mr. Campbell at his place of residence (Hayden, p. 19 & 104 cf. Rich., II:44). Both Rigdon and Bentley had been brought up within the bounds of the Redstone Baptist Association in Penn. The former, however had come from his early home in Allegheny county much more recently than the latter. It was possible, therefore, that Bentley got all the special information he had regarding the opposition which was there felt against Mr. Campbell, from the relations given forth by Rigdon himself. Sidney may have been from the outset favorably disposed towards Campbell, by reason of the circumstance that he was already the occasion of partisan division in the Association, where numbers inclined to favor him and others held the professed reformer in no esteem. Still it does not appear that Rigdon had previously enjoyed the honor of an intimate personal acquaintance with Mr. Campbell. That gentleman was a pretty diligent attendant at the sessions of the Redstone (Association, however and) he was a prominent figure at the meeting that occurred at Peter's Creek in August 1817 (Rich., II:47), and was appointed its secretary for the meeting in August 1818 (Benedict, 2nd ed. p. 615), more than a year after Sidney had become a communicant among the Baptists; but Rigdon was likely at that early time not in the custom of giving strict attention to the proceedings of the body. The two companions in travel arrived at the house of Mr. Campbell somewhere about the first of July 1821 (Rich., II:46), and, after passing a night under his roof, where they were hospitably refreshed, they pursued their way to their home in Warren. For both of them this visit was an important event. Though they remained in outward fellowship with the Baptist church for a season after it befell, they were each estranged from the Baptist faith by what they had learned from their host. To show the process and the completeness of this conversion it may be well to bring forward the account which Mr. Campbell himself gives of the affair, about 27 years after it was enacted. Writing in the "Millennial Harbinger" for 1848 (See also (Rich., II:44-46). Mr. Campbell says: In the summer of 1821, while sitting in my portico after dinner, two gentlemen in the costume of clergymen, as then technically called, appeared in my yard, advancing to the house. The elder of them, on approaching me, first introduced himself, saying, 'My name, sir, is Adamson Bentley, this is Elder Sidney Rigdon, both of Warren, Ohio.' On entering my house and being introduced to my family, after some refreshment, Elder Bentley said, 'Having just read your debate with Mr. John Walker of the State of Ohio, with considerable interest, and having been deputed by the Mahoning Association last year to ordain some elders and to set some churches in order, which brought us within little more than a day's ride of you, we concluded to make a special visit, to inquire of you particularly on sundry matters of much interest to us set forth in the debate, and would be glad, when perfectly at your leisure, to have an opportunity to do so. I replied that, as soon as the afternoon duties of my seminary were discharged I would take pleasure in hearing from them fully on such matters. After tea, in the evening, we commenced and prolonged our discourse till the next morning. Beginning with the baptism that John preached we went back to Adam and forward to the final judgment. The dispensations -- Adamic, Abrahamic, Jewish and Christian -- passed and repassed before us. Mount Sinai in Arabia, Mount Zion, Mount Tabor, the Red Sea and the Jordan, the Passovers and the Pentacosts, the Law and the Gospel, but especially the ancient order of things and the modern, occasionally engaged our attention. hand. They went on their way rejoicing, and in the course of a single year prepared their whole Association to bear us with earnestness and candor. The above lively representation seems to be tolerably correct except in what it says relating to the special circumstances under which the journey was performed to the residence of Mr. Campbell. In this respect it has been considered preferable to be guided by the information of Hayden who it is suggested enjoyed better means of information than the editor of the "Millennial Harbinger," concerning the details of Bentley's history. |

|

(Skip Campbellite roots section and continue with Sidney Rigdon material)

[ 026a - this section removed from original manuscript - 01 - [ 027 ] by this means she had lost the right to be styled a Church of Christ. In order to meet the objections of these adversaries, Mr. Glas resolved to investigate the whole question of national covenanting in the light of the Scriptures. The issue of these researches was different from anything he had anticipated. By means of them he not only withdrew the foundation of strict biblical precept from beneath the feet of the Cameronians, but the support upon which his own Church was established were, in his judgment, likewise destroyed. These covenants, whether in their ancient or their modern observation, proceeded all alike upon the supposition that a connection between Church and State is in accordance with the teachings of the Sacred Word. (Glas's Narrative, pp. 1-25, also p. 139.) On his attaining to the conviction that a union of this nature was not provided for in the New Testament, Mr. Glas became displeased with his own position in the Established Church, as well as with the representations of the Cameronians. He was more than ever confirmed in the resolution "to make himself no other rule but the word of God." His reflections upon that Word now speedily made him aware that the rite of communion, as it was observed in his own and other parishes, was not strictly in accordance with the pattern of the apostolic churches. Many persons of the weakest pretensions to pious living, and many more who made no claims to any special renewal by the Spirit of [ 028 ] holiness were entitled, in virtue of their birthright, to the benefits of a position at the table of the Lord. This posture of circumstances had become unendurable to him. Accordingly, on the 13th of July 1725, he sought to relieve his conscience by organizing a coventicle within the boundaries of his parish, composed of those only who he believed had experienced a complete change of heart. (Memoranda of John Glas and Robert Sandeman, collected from MS notes of the late James Scott, member of the church in Dundee; in, Letters and Discourses of Robert Sandeman, Dundee, 1851, p. 118. Compare also Glas's Narrative, pp. 103 and 113.) When the literalistic tendency of Mr. Glas had resulted in this ecclesiola in ecclesia, it became the means of directing public attention to his proceedings. A communion occasion at Strathmartine, on the 6th of August, 1726, served to bring him face to face with the opposition that was gathering head against him. Echoes of the rising strife were also heard in the Presbytery of Dundee, at its session on the 7th of September following. The affair likewise came to discussion, after an informal fashion, in the Synod of Augus and Mearns when it convened in October 1726. Nothing of consequence was done in the premises until the 17th of October 1727, at which date the Synod of Augus and Mearns laid upon the Presbytery if Dundee, to which the parish of Tealing [ 029 ] belonged, the duty of bringing Mr. Glas to trial at a special session which they should convene for that purpose; and ordered that these in turn should bring the results of their investigations before the Synod, at its next session at Brechin in April 1728. This mandate was observed; and after due deliberation was had, the Synod of Augus and Mearns, on the 18th of April 1728, pronounced a sentence of suspension from the ministry against Mr. Glas, for promulgating sentiments hostile to the National Covenants and to the union of Church and State in any form. An appeal was taken to the General Assembly, which convened about a fortnight later, on the 2d of May, which, however, confirmed the action of the Synod. Meanwhile, Mr. Glas having laid himself liable to the charge of contumacy by continuing to preach the obnoxious doctrine after his suspension from office, a sentence of deposition was passed against him by the Synod in October 1728. An appeal being taken against this new sentence, it was likewise confirmed by decision of the Commission of the Assembly, at a meeting appointed to consider the case, on the 12th of March 1730. (The above facts are taken from, Glas's Narrative, as cited on a preceding page.) The brief outlines which have just been given will avail, in some sort, to bring before the reader a view of the special occasion that induced Mr. Glas to rebel against the Kirk of Scotland, and of the main indictments of the process that was thereupon entered against him. His own reflections concerning the [ 030 ] teachings of the Scriptures had brought him to embrace the position of the English Independents in relation to the question concerning the proper church order, while the action of the constituted authorities had already destroyed his sympathy for the National Establishment. Though his followers and himself were in the custom of designating themselves, and the churches they subsequently organized, by the name of "Independents" (Glas, Narrative, p. 110; also Memoir of Mr. John Glas, prefixed to the Narrative, p. xvii), or some times Congregationalists (Memoir of Mr. John Glas, prefixed to the Narrative, p. xxvi), yet they made no effort to form relations with the people who in England bear those names. On the contrary, they stood wholly aloof; and guided by the Scriptures, they resolved to work out from this source, alone and without any assistance, the more minute details of the constitution, life, worship, and discipline of the churches of the New Testament period. The passion they had acquired for contradicting the usages and the doctrines of the "popular clergy" was so keen that they were soon driven into excesses; and before they progressed very far there had arisen so large a variety of convictions and useages, that many of the individual bodies differed from each other in regard to a number of particulars, while each single item, though never so insignificant in appearances, was likely to become an occasion of separation. - 06 - The tithing of mint anise and cummin, it has been suggested, became the principal concern of Mr. Glas and his believers. The work was begun only a few months after the sentence of deposition from the Kirk of Scotland had been confirmed. Mr. Glas had in uncommon amount of confidence in the capacity of the poorest of the brethren to divine the truth of God from the biblical word, and often boasted that he got hints from them which served to open and explain many things which he had not previously understood. During the summer of 1730, while he was absent in the Highlands for the benefit of his health, these humble people raised a scruple in the church over which he now presided in Dundee, regarding the ruling elders, which, as former Presbyterians, they had adopted from the constitution of the Established Church. The pastor was speedily fetched from his summer retreat for the purpose of adjusting the difficulty. This enterprise was accomplished by abolishing the office of ruling elders, and substituting in their stead a plurality of elders, whose duty it should be both to preach and to teach, (Memoranda of John [ 032 ] Glas and Robert Sandeman, as found in the Letters and Discourses of Robert Sandeman, pp. 118-119.) The fashion of employing a plurality of elders is likewise found among the Disciples of America, To an aged member of the church, also presumably one of the poorest of the people, is due the innovation of weekly communion in the Lord's Supper. The conventicle which Mr. Glas had gathered around him was at first in the habit of monthly celebrating the Lord's Supper. The person referred to suggested the inquiry why they should meet every mouth for that purpose, and not once or twice in the year, as the churches of the Establishment were in the custom of doing. A debate was held regarding the business, by means of which it was concluded that both of these practices were without example in the New Testament; and therefore the weekly service was enjoined. (Memoranda of John Glas and Robert Sandeman in the place above cited, p. 119.) The Disciples also observe this usage. In the beginning of the movement it was expected that the elders of whom there were indispensably two or three in every church, should sustain themselves, by their own exertions in some trade or profession outside of the ministry. This peculiarity has been retained, with considerable tenacity, in some of the Sandemanian churches (An Account of the Christian Practices of the Church in Barnsbury Grove, Barnsbury, London. 1878, p. 10.) The early Disciples in their turn, laid much stress upon this point [ 033 ] (Christian Baptist, edit. 6, p. 91, pp. 8, 29, 43, 37, 46); but of late they are becoming less strenuous regarding it. Seeing that he was now fairly launched upon a career of literalism, Mr. Glas would soon perceive that it was impossible to find in the New Testament writings any documents like the Longer and Shorter Catechisms of the Kirk of Scotland. Accordingly, in the year 1736, he published a pamphlet under the title of "The Usefulness of Catechisms Considered," and takes the occasion to discourage the employment of them by his followers. The Confession of Faith, in its turn, was abolished. Besides the fact that there was directly no Divine command enjoining its existence, the Westminster Confession had been, in some sort, the occasion of his displacement from the perish at Tealing. The attention of the party was soon directed to the love-feast which prevailed in the early Christian Church; and, with the courage of their convictions, this observance was also added as an indispensable mark of a genuine Church of Christ. Their successors in England are quite as stringent as were the Sandemanians of the eighteenth century in requiring the presence of each and every member on these occasions. (Barnsbury Grove, as above, p. 10.) Mr. Campbell the founder of the Disciples, seriously considered this matter; but, while he allowed that the custom was of biblical authority, and might be "found useful when the ancient order of things is restored" [ 034 ] (Christian Baptist, edit. 6, pp. 283-284), he yet lacked a sufficient amount of courage to enjoin the observation of it. On the other hand, he was fully as clear as the Sandemanians in his denunciations of church catechisms, creeds and confessions of faith, The Sandemanians were easily able to discover that the kiss of charity was several times enjoined in the apostolical letters, and hence this observance was frequently found among them. Mr. Campbell's courage and devotion to the distinct commands of the word of God failed him entirely at this point. (Christian Baptist, edit. 6, 224, Compare also Richardson, vol. ii. p. 129 where Mr. Campbell had an opportunity to resist this observance in a small church at Pittsburgh, which professed Sandemanian views.) The conditions were almost the same in the case of foot-washing. This practice was also regarded by numbers of the Sandemanians as an important mark of a true Church of Christ. It is still observed by them (Barnsbury Grove, p. 8), but they do not now appear to consider it of the same binding necessity as formerly. Mr. Campbell rejected it entirely (Christian Baptist, pp. 222-223), as a church observance, though he was not adverse that it should be performed as an expression of private hospitality. The Sandemanians early became convinced that it was an article of capital concern, that their adherents should abstain from eating blood. In this connection they insisted upon the letter of the passage at Acts xv. 20,28-29. No distinct allusion, on the part [ 035 ] of the Disciples, to the binding force of this apostolical prohibition, can be remembered. The Sandemanians laid unusual stress upon the intercessory prayer of our Lord, in the seventeenth chapter of the Gospel according to John; holding that it inculcates the necessity of absolute unanimity, on the part of the various members, in every transaction by an individual church. In order to obtain this indispensable unanimity. the parties who may entertain such objections as they are unable to surrender are incontinently expelled from the communion. (Barnsbury Grove, p. 14.) The Disciples likewise insist with earnestness upon the passage in question; but they understand that it refers to the organic union of all who profess and call themselves Christians, on the basis of the plea which themselves have a charge to urge upon the attention of the religious public. A modified type of communism prevailed, and is still professed, among the Sandemanians. (Richardson, Vol. I. p. 71.) The personal estate of a communicant could be retained by him after entering the fraternity, but always with the understanding that it was subject to the demands of the necessitous, especially those of them who chanced to be of the household of faith. Accordingly it was expected that their brethren should not lay up any further treasures on earth than such as they were possessed of at the time of their reception. (Andrew Fuller, Strictures on Sandemanism. Letter IX.) In order to prevent this from taking place, the surplus above their actual [ 036 ] necessities in the way of subsistence was to be contributed to the "Fellowship," which is the name they derived from Acts ii. 42, for the collection for the poor. (Barnsbury Grove, pp. 6-7, also pp. 8-9 cf. Letters and Discourses of R. Sandeman, p. 42) The Disciples, on the contrary, have never pressed the principle of communism to the same extent; but they have adopted the nomenclature of the Sandemanians in the matter of the weekly collection (Christian Baptist, edit. 6, pp. 209,166,359) which is ordinarily designated as "the Fellowship" in their literature. (See also Christian Baptist, pp. 339,391,408,413, for other instances of the employment of this term in the writings of Sandemanian churches.) The custom of mutual exhortation, as a regular part of religious worship, was in vogue among many of the Sandemanian fraternities. They justified this proceeding by a literal interpretation of 1 Cor. xiv. 31. It was often assigned a place in the observances of the Sabbath day; but the church of Barnsbury Grove, London, has now removed it to the Wednesday-evening meeting. (Barnsbury Grove p. 7.) The business of exhortation was likewise attended to in the first church that was organized by the Disciples in America, as also in the kindred Sandemanian church under the charge of Walter Scott in Pittsburgh, Penn,; but so many evils grew out of it, that after a series of years Mr. Campbell became impatient of it, and succeeded in persuading his followers to surrender their liberty in this regard. [ 037 ] (Richardson, Memoirs of A. Campbell, Vol. II. pp. 125-129.) A portion of the Sandemanian fraternity were so strict in their literalism, that, because there is no direct injunction commanding the observance of family prayer, and because there is a Divine command to enter into the closet and pray in secret, they would inveigh against this practice as savoring of a tendency to proselytism. (Christian Baptist, edit. 2, Buffalo, Va., 1827, p. 76.) Others of the party discouraged the habit of family prayer, on the ground that it is "unlawful, provided any part of the family be unbelievers, seeing it is holding communion with them." (Braidwood's Letters, as cited by AndrewFuller in his Strictures on Sandemanianism, Letter IX.) In his earlier years Mr. Campbell was influenced by this latter view of the subject, and at one time seriously proposed to his father the inquiry " whether family prayer is proper in a family composed in part of unbelievers." (Richardson, vol. i. p. 449.) Unlike the Sandemanians, however, who could find "no precept or precedent for family worship" in the biblical writings (Fuller, Strictures on Sandemanianism, Letter IX.), Mr. Campbell was fortunate enough to discover a justification of the practice in the patriarchal dispensation, which he denominated "the family worship institution" (Christian System, Bethany, Va., 1840, pp. 128-133); and, notwithstandingthe youthful scruples referred to above, he appears [ 038 ] to have performed the duty with a commendable degree of diligence and spirit. The same people who could not reconcile it to their views to pray or to enjoy any kind of religious observance in the family circle with those who mere not in communion with them at the Lord's Supper, yet had no scruples against accompanying respectable persons of whatever creed, or of no creed at all, to the theatre, or against joining with them in the dance or other social amusements which are commonly condemned by the more serious portion of the religious community, (Barnsbury-Grove, p. 9; compare Fuller's Strictures on Sandemanianism, Letter II; and Letter of John Glas to Edward Gorril, in Letters and Discourses of R. S., p. 88.) Mr. Campbell was not guilty of this kind of extravagance; but the sentiment of the Sandemanians in the matters of theatres, dancing; and other diversions, appears to have survived in the Mormon community, who, as will be suggested later on, are connected, through the Disciples, with the Sandemanian stock. It would he natural to expect that those who were unwilling to engage in family prayer where unbelieving members might belong to the household, should also be forward to propose objections to the presence of any but communicants at the public services of the Church. A portion of the Sandemanian Churches acceded to the demand of their peculiar logic in this particular, and were solicitous to exclude from their public worship all who might not belong to their own [ 039 ] community. (Christian Baptist, edit. 6, p. 389; also a Letter from the Elders of the Church in Dundee to the Elders of the Church in Edinburgh, as found inThe Letters and Discourses of Robert Sandeman, Dundee, 1851, pp. 116-117.) Mr. Campbell, in his turn, was much taken with this peculiarity of the Sandemanians. His biographer is our authority for the statement that the first church he organized -- at Brush Run in Pennsylvania -- did not recognize as duly prepared to partake in religious services any persons except such as had professed to put on Christ in baptism; or, in other words, those who chanced to be members of that special organization. Later in life he was persuaded to recede from this extreme position; but he appears to have always regretted his course in that regard, longing in vain for the exclusive attitude of his youthful time. (Richardson, vol. i. p. 454.) The Sandemanians made a deal of noise over the point that the first day of the week is not properly a Sabbath, at least holding that it is not a duty incumbent upon Christian people to observe it in the same fashion us the Sabbath was observed by the Jewish nation under the Old Testament economy. They regarded the Christian Sabbath as merely designed for the celebration of divine ordinances, (Barnsbury Grove p. 4.). and did not conceive that they were engaged to sanctify the day according to the strict usage of the Scottish Kirk. When the concerns of public worship had been duly cared for, the [ 040 ] balance of the day might be passed in such pleasures as would scarcely comport with the claim that it was anyway more holy than other days. (Andrew Fuller, Strictures on Sandemanianism, Letter IX.) The Disciples likewise decline to regard the first day of the week as a Sabbath, or even to call it by that name. The fourth command of the Decalogue, they hold, is applicable to the seventh day, but it does not refer to Sunday. On this account they have now and then been charged with the crime of paying no respect to the Fourth Commandment. Claims of that nature, however, are commonly based upon a misconception. The public worship which the Disciples, like the Sandemanians, consider it their duty to observe on the Lord's day, occupies about as many hours of time and service as customarily are passed in that way by those who are willing to consider the day as a Sabbath. The only matter worthy of attention in this connection is, that the party are in the habit of proposing the same distinction regarding the subject that was urged, before their time, by the Sandemanians. (Richardson, vol. i. pp. 432-435.) - 16 -