Mormon Classics | Spalding Library | Bookshelf | Newspapers | History Vault

|

William H. Whitsitt (1841-1911) Author of: "Sidney Rigdon, The Real Founder of Mormonism" (review of Whitsitt's Sidney Rigdon biography) |

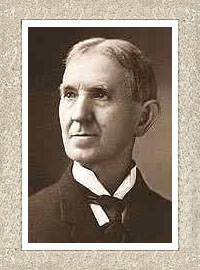

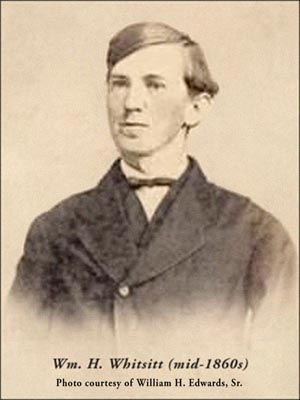

William Heth Whitsitt (1841-1911)

William Heth Whitsitt (1841-1911)

|

Whitsitt: Insights into Early Mormonism | Sidney Rigdon, Real Founder of Mormonism (1891)

1882 Mormon Lectures: #1 #2 | " Honolulu Manuscript" (1885) | "The Mormons" (1892)

|

A Very Brief Biography of Dr. Whitsitt

As a youth William H. Whitsitt attended Juliet Academy and then studied for the Christian ministry Union University, in Jackson Tennessee, graduating in 1861. Shortly thereafter he joined the Confederate army and was ordained as a Baptist minister within its officer ranks in 1862. He served the remainder of the Civil War as a Confederate chaplain. After the end of hostilities William resumed his higher education in attending first the University of Virginia and then the Southern Baptist Seminary, where he studied between 1866 and 1869.

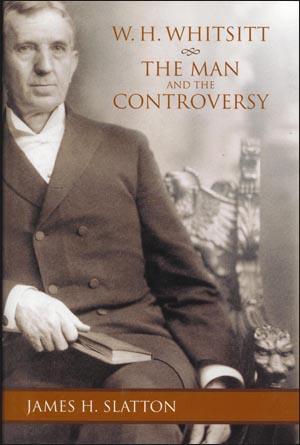

As one of the more promising Baptist seminarians of his day, Whitsitt was accepted at the University of Leipzig and at the University of Berlin where he completed his graduate studies in about 1871. Following his return to the United States in 1872, William first served as a Southern Baptist pastor in Albany, Georgia and then applied for a professor's position in Ecclesiastical History in the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary at Greenville, South Carolina. Whitsitt joined the staff of that school in the Fall of 1872 and moved with the rest of the staff when the seminary was relocated in Louisville, Kentucky in 1877. Prior to that relocation Whitsitt received his D.D. from Mercer University in 1874. Whitsitt taught the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary as a well respected professor of Church History and Polemical Theology until his elevation to the office of President in 1895, when he became the third head of the seminary since its original founding in South Carolina. Prior to his advancement to the Seminary Presidency he had married Florence Wallace of Woodford, Kentucky. The couple later had a son and a daughter and raised their family in Louisville. Whitsitt served with distinction in his new office, winning the respect of staff and students alike, even though his modern religious and theological views were considerably in advance of many members and other leaders within the ranks of the Southern Baptist Convention. While he was President the student body at the school became the largest in America and it has ever since retained one of the largest enrollments of any Christian seminary in the world. Problems at Southern Baptist Seminary As a student in Europe Whitsitt had conducted investigations into Baptist Church History and the gist of his findings there was somewhat contrary to accepted Baptist notions back in the States. In 1896, the year following Whitsitt's elevation to the Seminary Presidency, he had an article published in Johnson's Universal Encyclopedia which made public some of the understandings in Baptist history he had developed out of his European research. In brief, Whitsitt merely asserted that there had not been an unbroken continuance of the Baptist practice of immersion for adults seeking membership in the denomination. It was practically an article of faith among many Southern Baptists during that period that their ordinance of adult baptism by immersion had been handed down from generation to generation all the way back to New Testament times. Whitsitt's assertion appeared to many to be an undermining of Baptist legitimacy and authority. Whitsitt's progressive approach to ecclesiastical matters, along with his controversial stance in theological and historical discussions, soon raised severe problems for him and his adherents within the Southern Baptist Convention. While Whitsitt received some support from the trustees of the Seminary and other scholars, an opposition, led by T.T. Eaton, editor of The Western Recorder, prevailed and the Seminary President soon found himself and his views quite unpopular among certain influential Baptist circles. By 1898 the controversy among the Southern Baptists had reached such heights that the denomination's future support for the Seminary was in doubt. Although Whitsitt's views would win out in the long run, he was currently causing too much trouble to continue in the highly visible position of President of the Convention's flagship seminary. With dismissal a very real possibility, Whitsitt tendered his resignation, effective June 1, 1899. After taking a few months to get his personal and professional affairs in order he accepted a professor's position in the Department of Philosophy at Richmond College in Virginia. He remained there as a professor of Theology and Philosophy until 1910. Between 1908 and 1910, seeing the end of his life before him and having amassed a considerable volume of research and personal papers, Whitsitt made preparations to have his papers donated to the Library of Virginia in Richmond and to the Library of Congress in Washington, DC. Following his death on Jan. 20, 1911, his widow saw that his wishes were carried out and the papers were included in the files of those institutions. Whitsitt's Biography of Sidney Rigdon One of the more interesting unpublished works among his papers at the Library of Congress is the manuscript for "Sidney Rigdon, the Real Founder of Mormonism," a collection of typewritten index cards affixed to over 500 letter-sized sheets of paper. In addition to its unusual subject matter, the manuscript may be of some interest to historians of the early use of the typewriter in American scholarly writing and publishing. On Feb. 16, 1886, in a letter to James H. Fairchild of Oberlin College, Whitsitt had this to say about his Rigdon biography: My dear Sir, Although Whitsitt mentions having "810 pages" of this biography "ready for the printer" early in 1886, the work never saw publication. A relatively small section of the text was excerpted in 1888 and was published by A. C. Armstrong of New York City as Origin of the Disciples of Christ (Campbellites); a contribution to the centennial anniversary of the birth of Alexander Campbell. Beyond this, only one other minor fragment of the text and a summary of the biography were ever put through the press. In August of 1908, Whitsitt wrote the following letter to Dr. Worthington C. Ford, the Chief of the Manuscripts Division of the Library of Congress: Dear Doctor Ford: In this letter Whitsitt mentions "letters" which were sent to him "by many persons" following the printing of his 1891 article in Jackson's While Whitsitt will probably be best remembered for his contributions in Baptist History, it is conceivable that his biography of Sidney Rigdon will yet receive some belated attention from historians of the Disciples of Christ and Latter Day Saint restoration movements during their earlier phases. Should any of Whitsitt's singular theories regarding Mormon origins ever be proved true, he will perhaps be accorded a substantial amount of credit in future histories of the Latter Day Saints. For more on the life of Dr. Whitsitt, see James H. Slayton's 2009 W. H. Whitsitt.

Whitsitt's Writings, Publications, etc. 01. "Position of the Baptists in the History of American Culture," (no additional information available on this article's publication) 02. "The History of the Use [Rise?] of Infant Baptism," 1878 03. "The History of Communion Among Baptists," 1880 04. "Wm. H. Whitsitt's Lecture" (Book of Mormon, baptism, etc.) Louisville, Western Recorder, Oct. 26, 1882 05. "The Honolulu Manuscript and the Book of Mormon" (article in the Syracuse New York Independent, October 1, 1885) 06. "Solomon Spaulding's 'Manuscript Found' -- Editor's Comments" (unsigned reply in the Syracuse New York Independent, January 7, 1886) 07. Spencer, J. H., A History of Kentucky Baptists From 1769 to 1885, Including More Than 800 Biographical Sketches... privately printed, 1886 reprinted: Lafayette, Tennessee, Church History Research & Archives, 1976 08. Life and times of Judge Caleb Wallace, some time a justice of the Court of appeals of the state of Kentucky, Louisville, J. P. Morton & Company, Printers, 1888 (151 p.) 09. Origin of the Disciples of Christ (Campbellites); a contribution to the centennial anniversary of the birth of Alexander Campbell, New York, A. C. Armstrong, 1888 (112 p.) 10. Sampey, J. R., Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1859-1889, Louisville, 1890 11. "Mormonism" (summarizes Whitsitt's theories on Sidney Rigdon) Jackson, Samuel M. (editor) Concise Dictionary of Religious Knowledge and Gazetteer, NY, The Christian Literature Co., 1891 12. "An Article on Baptist History," in Johnson's Universal Encyclopaedia, NY, 1896. 13. A Question in Baptist History: Whether the Anabaptists in England Practiced Immersion Before the Year 1641... Louisville, C. T. Dearing, 1896 (164 p.) reprinted: NY, Arno Press, 1980; Ayer Company Publishers, [1997?] 14. "Whitsitt, William Heth," in Malone, Dumas (editor) Dictionary of American Biography, Vol. X 1896, NY, Charles Scribner's Sons. 15. "Whitsitt, William Heth," in The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, NY, James T. White & C., 1900 16. "Annals of a Scotch-Irish Family -- The Whitsitts of Nashville, Tenn," in American Historical Magazine and Tennessee Historical Society Quarterly, Jan., July, Oct., 1904 17. Genealogy of Jefferson Davis; address delivered October 9, 1908 . . . Richmond, Everett Waddy Co., Printers, 1908 (16 p.) 18. "William H. Whitsitt's Obituary," in the Richmond, VA Times-Dispatch, Jan. 21, 1911. 19. "William H. Whitsitt's Obituary," in the Louisville, KY Western Recorder, Jan. 23, 1911 20. Who's Who in America, 1910-1911, NY, 1912 21. Nowlin, W. D., Kentucky Baptist History, 1922 22. Patterson, W. Morgan, "William Heth Whitsitt : the Seminary's Versatile Scholar," (Southern Baptist Theological Seminary Founders' Day Address), Louisville, Privately Printed Typescript, February 1, 1994. (24 p.) For further reference see: Papers. Whitsitt, William Heth, 1841-1911. Library of Congress, Manuscripts Division: mm77-60863 Papers. Whitsitt, William Heth, 1841-1911. Library of Virginia, Richmond, (Microfilm: Misc. Reels 37-39) The Whitsitt Journal. (misc. articles in various issues) Macon, Georgia, William Whitsitt Baptist Heritage Society. Vol. 1, no. 1 (July, 1994) -- |

Return to top of page

Return to top of page

Return to top of page

|

Southern Baptist Theological Seminary LOUISVILLE, KY, Intermediate Examination, January 6, 1886. Polemic Theology Prof. WM. H. WHITSITT. I. (12.) LITERARY STRUCTURE OF THE BOOK OF MORMON. -- How many redactions does internal evidence indicate that Mr. Rigdon made of Spaulding's Book of Mormon? What event rendered a second redaction important, and when and where was it performed? Did he make any alteration of the first portion of Spaulding's title of the volume? To what point in the volume did "the abridgment of Mormon" extend, and from what source were the materials which Mormon is given out to have inscribed upon his "plates," said to be derived? In the present Book of Mormon where does one first touch the "abridgment of Mormon?" How should the title page be altered in order to truly describe the contents of the volume? What books are included in the so-called "small plates?" The real secret of the existence of these "small plates?" Why did not Mr. Rigdon prosecute to the end the labor of rewriting Spaulding's Book of Mormon? Why was that section of the "abridgment" that was replaced by Mr. Rigdon's "small plates," and called by Joseph the "sealed portion of the plates," never published? Where did the book entitled "Words of Mormon" originally stand? Why was it removed to its present position? Proofs that Spaulding wrote the Book of Ether before writing the "abridgment of Mormon." Who is the sole author of the Book of Moroni? II. (84.) DOCTRINAL SYSTEM OF THE BOOK OF MORMON. A. Theology. -- How many Gods does it provide for? Its position regarding anthropomorphism? Argument for the continuance of miracles and all gifts of the spirit, derived from the unchangeableness of God; does it represent God as the Creator of all things? Explanation of the origin of evil and [the] source when this explanation was derived; in what way does it represent the fall of man as a blessing? Is it Arminian or Calvinistic in it attitude towards predestination? B. Christology. -- Leading object for which the book is said to be composed, and the source whence that object was obtained; attributes and works ascribed to Christ; his relation to the Father; effect of his resurrection upon the unrighteous dead. C. Pneumatology. -- Is the personality of the Holy Spirit assumed? The word alone system" in reference to the operations of the Spirit on the hearts of men, and the source whence it was derived; doctrine of the Trinity. Is the tenet of a duality of persons, in the Godhead which appears in the "Lectures on Faith," anywhere mooted in the Book of Mormon? D. Anthropology. -- Is anything hinted regarding the pre-existence of man in a spiritual form? Whence was that notion later derived? How did the presence of the tree of knowledge impart freedom to Adam in his earliest estate? E. Soteriology. -- Are the person and work of Christ indispensable to salvation? Doctrine of the book touching Universalism and Restorationism; name by which people who embrace the Saviour must be called in their individual and collective capacity; respectively, and the source whence it was derived; source of Mormon notions regarding the "kingdom" of Christ; two different doctrines touching the ordo salutis, and the five points of the second ordo salutis; reason why a change of the ordo salutis became important. Who added the item of imposition of hands, and when was it done? Was Mr. Rigdon friendly to that change? F. Ecclesiology. -- (1). Constitution of the church. Is infant baptism tolerated? What three office bearers does the book provide for? Explanation of the fact that both priests and teachers are provided for; origin of the designation "teacher;" why were not deacons provided for, and who brought them into the Mormon Church? Origin of the designation "stakes" for individual churches? Place where the lost ten tribes were supposed to be concealed and their relation to the Mormon church when they should be found? How often was the church required to meet for worship? Position regarding the exclusion from the worship of the church of such as were not members of the church, and special reason why it was insisted upon. (2). Religious Life. -- In what form does the institution of the "fellowship" appear, and whence was it derived? How does the community of Isaac Morley, at Kirtland, account for several injunctions in the second redaction favoring communism? Position regarding the support of the ministry, in connection with the cant word "popular;" position touching polygamy and Masonry: whence was derived the tendency to cultivate dancing and theatres. (3). Means of Grace. -- Position ascribed to the Bible and the Book of Mormon. Were any further revelations provided for in the first redaction of the Book of Mormon, and why were they recognized in the second redaction? Number of sacraments; form and design of baptism; design of the supper; whence was derived the difference in respect of the kind and degree of efficacy ascribed to baptism and the supper? Whence comes the weekly communion? G. Eschatology. -- Signs of the Millennial craze, and source whence it was derived; the second petition of the Lord's Prayer; how is the "gathering" connected with the Millennial craze? Length of punishment of the wicked; is hell-fire a literal fire? Point out in detail which of the above items were derived from the Disciples of Christ, and show how these demonstrate that no person but Mr. Rigdon could have been the author of the doctrinal system of the Book of Mormon. III. (6.) GEOGRAPHY AND HISTORY OF THE BOOK OF MORMON. Proof from the Book of Mormon that the Hill Cumorah, where Joseph claimed to discover the "plates," is situated in the vicinity of the Isthmus of Panama, rather than in the vicinity of Lake Ontario. Proof that the geography and history of the Book of Mormon were derived by Mr. Spaulding from William Robertson's History of America. Time, 8:30 A. M. to 6 P. M. Form of certificate to be added at close of examination papers: -- "I certify that I have neither given nor received any sort of assistance during the progress of this examination." |

Return to top of page

|

William H. Whitsitt letter to James H. Fairchild (excerpts). 306 E. Chestnut, Louisville, Feb. 16, 1886 My dear Sir, After diligent consideration of the subject you are good enough to bring to my attention, I some while ago reached the conclusion that Mr. Sidney Rigdon supplies the right key to Mormon history and theology. In pursuance of that conviction, I have prepared a Biography of Sidney Rigdon, of which 810 pages are now ready for the printer. A few of my chapters which dealt with the Book of Mormon were read before one of my classes and made the topic of my intermediate examination. Mr. Rigdon was a Disciple minister at the moment of producing the particular form of the Book of Mormon which we are now familiar with, and I discovered that it contains all the leading tenets and peculiarities of that people. The contents of the volume, at least to my thinking, will supply a demonstration that it could have been prepared by none but a Disciple theologian, and further that it could have been prepared by no Disiciple theologian except Mr. Rigdon. This is what I consider to be my personal contribution to the sum of knowledge on this subject. The question touching the Spaulding manuscript has no direct connection with that result; it stands upon its own merits, just as truly as if no such person as Solomon Spaulding ever existed. I was solicitous to avoid the Spaulding controversy entirely, for the reason that it has no real connection with the business. But having set my hand to compose a biography of Mr. Rigdon, I felt somewhat bound by the nature of the task to express an opinion. Here I have given attention almost exclusively to the only original authority in existence, namely Howe, pp 279-290. Citations have also been made from a pamphlet entitled "Who wrote the Book of Mormon?" by Robert Patterson of Pittsburgh, but with caution, for the reason that he has too much credulity and too little criticism. I am also indebted to a few passages in Hayden's "History of the Disciples on the Western Reserve," and in Mr. Alexander Campbell's "Millennial Harbinger." In my treatment I have felt myself impelled to reject a great deal that passes current in the literature of the subject: but I have reluctantly assented to the chief point that Spaulding wrote the Book of Mormon under that title also, and that Mr. Rigdon by some kind of process got possession of it. Nay, I have even gone to the length of suggesting a theory of my own in explanation of that process. That theory is different from any other that has been preached, and I cannot avoid to regard it as the weakest point of my performance; I am too often constrained to have resort to such words as "likely" and "perhaps". . . In a word my demonstration, satisfactory to my [mind?], without any kind of reference to the inquiry whether Rigdon had any connection with the Spaulding Manuscript. When I had concurred the point that Mr. Rigdon made use of the Spaulding manuscript of the Book of Mormon, I felt under obligation [of] an industrious inquiry to examine the volume with reference to the question [of] where Mr. Spaulding obtained the materials that he collected in his history. The conclusion which was reached in this quarter is likewise regarded with modesty; it is not conceived to amount to a demonstration. I have placed nearly every fact and incident that I have touched in a different setting from any that it ever before received. I hope to do myself the honor to submit my book to your inspection, and I desire to entreat you in advance not to accuse me of any passion for novelty. On the contrary, novelty is for me the "abomination of desolation standing in the place where it ought not." The different light in which I consider the subject is due entirely to the different point of view which I occupy. Will you not kindly investigate and determine whether the new light is a true light before you shall condemn my conclusions? I have derived the theology of Mormonism from the Disciples and from the Swedenborgians and from the Restorationists. These excellent people, I foresee would be very much enraged against me, but I do not feel the slightest hostility against them; I am simply exercising the right of every student to prosecute a thorough investigation. Mormonism, I believe, can be understood by no other process than that which I have advocated. If in any way you should ever feel disposed to employ your kind offices to relieve a fellow soldier from undeserved obloquy, it would be accepted as the kindest favor you could bestow. I consider that I am guilty of no offense except what is involved in a more complete and critical use of the inductive method than has been achieved by my predecessors in this field. yours very truly, Wm. H. Whitsitt P. S. Please accept thanks for your kindness in bringing my examination paper to the attention of Prof. Fisher. I perceive that I mentioned above nothing but the external sources upon which I relied for evidence that Rigdon got possession of Spaulding's Book of Mormon. There are also internal sources of perhaps more importance derived from the literary structure of the present Book of Mormon which to my way of thinking supply valuable evidence to show that the present Book of Mormon is based upon a work that preceded it. This latter evidence, however, does not certify that it was Mr. Spaulding's Book of Mormon; it might have been some other person's Book of Mormon. That Rigdon acted as editor and not in the character of author I believe will be apparent to any critical inquiry into the structure of the present B. of Mormon. I should be thankful for any information that may be in your possession regarding a nest of Mormons that existed in 1832 at Amherst, Lorain Co. How they chanced to obtain a footing there; what church they previously affiliated with; names of prominent persons; names of Mormon elders who perverted them; [these] are some of the points I should write to learn about. If I could get a sight of the autobiography of P. P. Pratt, I should likely not have any need to inquire. Is that work in your library? Have you any other rare books of the early period besides Howe? If it will go any distance to promote your inquiries I will add that Warren Smith and his wife Amanda (daughter of Ezekiel and Fanny Barnes) were Amherst Mormons in 1832. The latter was a member of the Disciples' Church and possibly her husband likewise.

William H. Whitsitt letter to James H. Fairchild (excerpts). [information from envelope] Moore & Warner Attorneys at Law Clinton, Illinois Return if not delivered in ten days Professor Whitsitt Louisville

Clinton Ill, May 18 '86

Professor WhitsittLouisville Ky, Sir In reading my "Magazine of Western history," I see that you are writing a history or biography of Sidney Rigdon. I knew him very well while he was in Mentor Kirtland & want one of your books as soon as published. I think the external & internal evidence strong that he had much to do in getting up the theology of the "book of Mormon." It is nearer that held by the 'disciples" than any other. I hope you have been able to find something that will [ 2 ] show that he knew all about it. Rigdon in his quarrel with Taylor Young Kimball and others, immediately after Jo Smith was murdered, threatened(?) them, with telling the whole story, they dare him to do it with dark haunts(?) as the consequences. I have often thought if some shrewd detective could have got hold of Rigdon after he left the Mormons at Nauvoo, he would have told, honestly told, all he knew about the origin of the book of Mormon. So far as I have read he died with out saying a word for or against it. His daughters Nancy & Authalia are yet alive, or were about a year ago. The most damaging evidence against Rigdon personally, is that taken before the Judge of the Fifth [ 3 ] Circuit of Mo on the arrest of Smith and others for treason, and given by W. W. Phelps, a P M in Caldwell Co Mo. The pamphlet was printed by Sharp & Gamble Warsaw Ill in 1841. For Rigdons threats please see pages 177, 8 & 9 of "The Mormons" published in London in 1857. When a small boy say from 1826 to the spring of 1831 I knew Rigdon. Have heard him preach often as a "disciple." He joined the Mormons early in the winter of 1830, 31. From that time until he left Kirtland I saw him but little but heard much. I am inclined to the opinion, that the manuscript coming from Honolulu is not the one named by the witnesses who have heard Spauldings manuscript read. [ 4 ] The scriptural language and the names of "Nephi" & "Lehi" could not be confused with those in that pretended "Manuscript Found." Again the Mormons themselves may have had that "Manuscript Found" written sealed up and afterward sent to the place where this was discovered for the express purpose of disproving our theory of the Mormon religion. They would have more interest in having just such a paper formed and found at the time it was, than any other sect. I don't think Rigdon was or intended to be a bad man. He was vain man, loved to talk, and chafed if(?) muted(?) because he was not in the estimation of the brethren the equal of Thomas Campbell or his son Alexander's. Respectfully Yours C H Moore Note 1: C. H. Moore, Clinton, Illinois, to William Heth Whitsitt, Louisville, Kentucky, 18 May 1886, ALS, Special Collections, Boyce Library, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, Louisville. This letter can be found in Whitsitt's Scrapbook, Clippings on Mormonism, in the SBTS Archives. Call number: 286.1081.W617m V.19 Note 2: Clifton Haswell Moore was born on October 26, 1817 in Kirtland, Ohio, the oldest of eight children to Isaac and Philena Blish Moore. He worked on his father's farm while attending school at the Painesville Academy and the Western Reserve Teachers' Seminary. He moved to Illinois in 1839. He began reading law and was admitted to the bar in 1841. And soon thereafter settled in Clinton Illinois where he established a law office. Eventually his son-in-law Vespasian Warner became his junior partner. Moore became friends with Abraham Lincoln when he was riding the circuit through Dewitt County. They were law associates working together on many cases and opposing each other on many more. Mr. Moore attended the National Convention in 1860 and is said to have done much toward securing Lincoln's nomination for president. Moore died on April 29, 1901 at the age of 83. See: "About C. H. Moore," http://www.chmoorehomestead.org/mrmoore.htm; (accessed June 5, 2006). |

Return to top of page

|

Wm. H. Whitsitt article from: Jackson, Samuel Macauley, (editor) The Concise Dictionary of Religious Knowledge

and Gazetteer (NYC: 1891; text from 2d. rev. ed., 1899, used here).

Structure of the Book of Mormon: Fifteen separate books are contained in the work, as follows: I NEPHI, II NEPHI, JACOB, ENOS, JAROM, OMNI, WORDS OF MORMON, MOSIAH, ALMA, HELAMAN, III NEPHI, IV NEPHI, MORMON, ETHER, MORONI. The plan of the work represents that the prophet Mormon composed an abridgment of the previous history of the prophet Nephi which he had taken from the plates of Nephi. In the above list all of the books from I Nephi to IV Nephi are included in the so-called Abridgment of Mormon. The book of Mormon, proper, which stands as 13th in the list, is not a portion of the Abridgment; it was composed as an independent work by the prophet Mormon and affixed as a supplement at the close of the Abridgment. The book of Ether is a separate and independent work that has no connection with the Book of Mormon. The prophet Mormon was in no sense the author of it, and it was included because the editor took a fancy to its contents. The Book of Moroni, which stands last in the series, was produced entirely by the editor, and appended to the work for a special purpose. It was an afterthought. It therefore appears that the Book of Mormon is composed of three separate and independent sections -- namely, the first thirteen books, which are represented to be the work of the prophet Mormon; the fourteenth book, called Ether, with which Mormon had no connection; and the fifteenth book, that was sent forth by the editor under the name of Moroni, the surviving son of Mormon. Returning to the first section, it may be remarked that the Abridgment of Mormon is also divided into two sections. The editor undertook to rewrite and recast the whole of the Abridgment, but his industry failed him at the close of the book of Omni. There he allowed the Abridgment to stand pretty nearly in the language of Mormon, only inserting here and there such preachments and reflections as suited the scope of his enterprise. The first six books that he had rewritten were given the special name of the small plates, the original upon which the so-called plates were founded being retained for future uses; but owing to circumstances that could not be controlled, it was never permitted to see the light. The book called The Words of Mormon, in the original work, stood at the beginning as a sort of preface to the entire Abridgment of Mormon; but when the editor had rewritten the first six books he felt that these were properly his own performance, and the Words of Mormon were assigned a position just in front of the Book of Mosiah, where the Abridgment of Mormon took its real commencement. So much for the handiwork of the editor, who brought the Book of Mormon into shape in which it now appears. Editor of the Book of Mormon: The question may now be raised as to who was the editor of the Book of Mormon. That point can be settled in no other way than by means of a critical examination of the doctrinal contents of the work. This examination would require much time and space, and here is not the place to prosecute it; nothing but results can be submitted. The first point that is claimed to be established is that the editor was a divine of the Disciples persuasion. In its theological positions and coloring, the Book of Mormon is a volume of Disciple theology, by which, however, is not meant the Disciples ever taught or practiced polygamy, or any of the errors commonly associated with Mormonism. That conclusion is capable of demonstration beyond any reasonable question. Let notice also be taken of the fact that the Book of Mormon bears traces of two several redactions. It contains in the first redaction that type of doctrine which the Disciples held and proclaimed prior to Nov. 18, 1827, when they had not yet formally embraced what is commonly considered to be the tenet of baptismal remission, a term, it should be remarked, repudiated by the Disciples. It also contains the type of doctrine which the Disciples have been defending since Nov. 18, 1827 under the name of the Ancient Gospel, of which the tenant of so-called baptismal remission is a leading feature. All authorities agree that Mr. Smith obtained possession of the work on Sept. 22, 1827, a period of nearly two months before the Disciples concluded to embrace this tenant. The editor felt that the Book of Mormon would be sadly incomplete -- would fail to accomplish the purpose for which he had bestowed his labor upon it- if this notion were not included. Accordingly he found means to communicate with Mr. Smith, and, regaining possession of certain portions of the manuscript, to insert the new item. Purpose of the Book of Mormon: The Disciples were continually making the boast that they and they alone spoke where the Scriptures spoke, and kept silent where the Scriptures are silent. The Editor of the Book of Mormon was deeply impressed by that sentiment. He was not even content with the extravagances of the Disciples; he longed to make the boast true of them that where the Scriptures spoke they always spoke, and felt convinced that the so-called Current Reformation would be a failure unless its advocates would consent to adopt also the Ancient Order of Things, touching such items as the gift of speaking in unknown tongues, of working miracles, communing with angles, the gift of inspiration and of revelation. His design was to bring the people with whom he was associated to adopt these changes, and so to fulfill the assertions that they enjoyed so much to repeat with reference to their merits as strict constructionists. A Limitation of the Editor of the Book of Mormon: Notwithstanding his almost insane devotion to false literalism, the editor of the Book of Mormon was unwilling to speak where the Old Testament Scriptures speak in relation to polygamy. He introduced into the work special injunctions that the faithful, who should receive it as a divine revelation, must abstain from polygamy. Mr. Sidney Rigdon: The above specifications, which may all clearly be demonstrated out of the Book of Mormon, point to Mr. Sidney Rigdon (q.v.) as the theological editor of the book. Rigdon was the only Disciple minister who vigorously and continuously demanded that his brethren should adopt the additional points that have been indicated. He was also the Mormon leader who resolutely opposed polygamy when Mr. Smith received his famous revelation in 1843. His opposition drove him from the counsels and fellowship of that portion of the Saints which remained faithful to Smith and his measures. That Rigdon was a Disciple minister for a short time is conceded by the Disciples themselves, and that he was a convert from Baptist views, having been a Baptist minister previously, explain his zeal in propagating his new views as he understood them. Spaulding and the Manuscript Found: Whatever may be true in relation to Solomon Spaulding, the conclusion is inexpugnable that Mr. Rigdon had in his possession the manuscript of the Book of Mormon before it was delivered to Joseph Smith. To suppose that Joseph Smith, whose antecedents were Methodistic, and who at this period had no acquaintance with the Disciples or their sentiments, could have given the work the special theological coloring that it displays, would have been unreasonable. Though none of the actors in the Mormon drama has chosen to reveal the secrets of Rigdon's initiative, the Book of Mormon points to him on almost every page. Its testimony cannot be concealed or denied. Nevertheless a measure of truth may be conceded to the stories that are reported concerning Spaulding. Criticism must allow that blunders are found in those stories, and that they cannot be accepted in all their details. For example, it is incorrect to affirm that Spaulding wrote only one Manuscript Found; that was likely a generic title for all his literary effusions. The first writing that he produced under that title is believed to be the document that several years since was recovered in Honolulu. The second of his Manuscripts Found is suspected to have been the Book of Ether, and the third the Book of Mormon. It is affirmed that he continued to drivel a Manuscript Found even after he had quitted Pittsburgh and retired to Amity, Pa., where his death befell in the year 1816. It is also a fable which represents that Mr. Rigdon was ever a printer in Pittsburgh. Most probably he obtained the Manuscript Found from the printing office of Butler and Lambdin upon the occasion of their failure in business, a number of years after Spaulding had deposited it with Patterson, Lambdin, who had been their predecessors. He may have purchased it for a mere trifle at their enforced sale (1823?) or, it may have been presented by Mr. Lambdin, who would be pleased to get rid of a bundle of useless rubbish. Most of the stories that have been put forth in the name of Mrs. Spaulding, widow of Solomon Spaulding, are unworthy of credence. This good lady knew almost nothing concerning the literary occupations of her worthless husband, and was hardly prepared to be a witness in the case. Especially the statement that appeared over her signature on April 1, 1839, was improperly obtained, and she was not fairly responsible for it. Mr. Joseph Smith: Taking our stand upon the unquestionable testimony of the Book of Mormon to the effect that Mr. Rigdon was its editor, it may be inquired by what process his attention was first directed to Mr. Joseph Smith as a suitable agent to bring the work before the public. Here, it must be conceded, the investigator is much at a loss. No record has been kept of the peculiar fortune by which a minister of religion, residing at the moment in Pittsburgh, Pa., could have had his thoughts first drawn to a smart Yankee Lad of eighteen years, who resided in Manchester, in the northern portion of New York. Happily the question is not or much consequence; nobody can doubt the fact that he did find him. The first interview of the pair appears to have occurred on Sept. 21, 1823, when Sidney must have shown himself at the humble home of Joseph and passed a night with him. In subsequent years Mr. Smith liked to adopt a pictorial method in accordance with which Sidney was raised to the dignity of an angel. His mother, however, in a contemporary utterance, gave a description of the pretended angel that would fit the figure of Mr. Rigdon very well. In the earlier years of Mormon history this angel was represented to be the angel Nephi, but upon subsequent consideration his name was changed to Moroni. That would agree well enough with the fact that Rigdon in his own person as editor had added the Book of Moroni at the close of the Book of Mormon. Mr. Rigdon had no idea of committing such a precious treasure and such an important enterprise to the providence of a lad of 18 years. Joseph was as yet too young and too giddy to receive the golden plates, but he nursed him assiduously for four years. It is conceivable that upon every return of Sept. 22, down to the year 1827, he went to New York to confer with him; at any rate, Smith annually made a demonstration at the Hill Cumorah when the day returned. He was justly suspicious of him, especially in view of the fact that Mr. Smith had become a trifle addicted to strong drink. Evidences are not wanting of a purpose to obtain a partner for Smith, so that the one might watch over and assist the other. Finally, on Jan. 18, 1827, Mr. Smith eloped and was married to Miss Emma Hale. All thoughts of a different partner were now dismissed, and Sidney resolved at the next anniversary to proceed with his project and deliver the Book of Mormon to his collaborator. . . . Mr. Rigdon kept his tryst and fulfilled his promise. After retaining the Book of Mormon for at least four years, during which at odd times he had been employed in the task of impressing on it a system of theology as much as possible in keeping with the scheme of the Disciples, the time was felt ripe to entrust it to one who had undertaken to get it published. The requirement that it should be copied before it was exhibited to the printer was a severe one, but it was felt to be necessary. The sheets were possibly yellow with age, but no printer in the land would concede that they were made of gold. It was indispensable that they should not be examined. Besides it was conceivable that in case they were widely circulated some person might examine them who should recognize the handwriting of Mr. Rigdon.... (remainder of article not yet transcribed) |

Return to top of page

Whitsitt's "Untold Story" of Introduction: In 1980, while working on my Master's degree in Ohio, I was informed by RLDS Elder and historian F. Mark McKiernan, of the existence (among the manuscripts in the Library of Congress) of a lengthy unpublished manuscript biography the early Mormon leader Sidney Rigdon. I procured a microfilm copy of this manuscript and found it to be the same biography cited in Reed C. Durham's 1965 BYU PhD dissertation ("A History of Joseph Smith's Revision of the Bible") as: Whitsitt, William H. "Sidney Rigdon, The Real Founder of Mormonism." Unpublished Manuscript, Library of Congress, 1881-5.Further investigation into the background of this obscure biography led me to realize that the work had been known to a handful of LDS and RLDS historians since the late 1950s, when Stanley Ivins (the son of Apostle Anthony W. Ivins) had obtained a copy of Whitsitt's work and circulated its contents among a small circle of his associates in Utah. Frustrated at not having an easily accessible and legible copy of the Rigdon biography available to me, I printed out the contents of the microfilm in 1980 and constructed a partial typescript. These pages I donated to the Special Collections of the Marriott Library at the University of Utah a couple of years later. Shortly thereafter, Mormon origins researcher Byron Marchant made use of my materials at the University to construct the first lengthy typescript of William H. Whitsitt's "Sidney Rigdon, The Real Founder of Mormonism." This he published in a very limited edition in 1988 (see one of the few surviving copies of that printing in the BYU H. B. Lee Library Special Collections: BX 8670.1 .R44w 1988). As of early 2001, three separate Whitsitt research and writing projects are underway. Before the end of 2002 a bibliography of Whitsitt's published and unpublished writings (accompanied by excerpts taken from several of his texts) will likely see completion, along with a graduate thesis documenting the man's life and works. To these major scholarly contributions can be added the scheduled 2002 publication of an annotated edition of the entire Rigdon biography by Metamorphosis Publishing. Given this renewed interest in Dr. Whitsitt and his biography of Sidney Rigdon, it now seems timely for me to resurrect and slightly modify the following review, which I first wrote and placed on-line in 1999. After my initial posting of its contents to the web several months ago, I received feedback informing me that some readers felt its contents demonstrated an unscholarly bias and included plethoric remarks censorious of Fawn Brodie and Jerald and Sandra Tanner. These imperfections I have attempted to remove in this April 2001 version of the review. 01. Rigdon's Connection to the Mormons: The Rev. Sidney S. Rigdon (1793-1876) was a very important early convert to the Church of Christ, founded in 1830 by Joseph Smith, Jr. Joining the Church at the end of that same year, Rigdon rose almost immediately to the highest levels of Mormon ecclesiastical authority, displacing Oliver Cowdery as Smith's right hand man. Elder Rigdon was an experienced "Reformed Baptist" clergyman, a capable writer and preacher, a compelling orator, and a visionary in his own right. Through the years of Mormonism he always managed to maintain at least a token presence in the Mormon hierarchy. After the failure of his 1839-40 misison to Washington, D. C. to obtain a Federal redress for Mormon losses in Missouri, Elder Rigdon's star began to fade. Except for his brief rehabiliatation to serve Smith's running mate in the 1844 U.S. Presidential campaign, Rigdon remained a figure of little importance during the Nauvoo period in Mormon history. He was ejected from the Church's membership by Brigham Young and Young's associates shortly after Smith's death in 1844. While the lives of many other early Mormon notables later became the subjects of intense interest and study, Rigdon's acrimonious excommunication (coupled with his subsequent efforts to build up a Latter Day Saint movement under his own leadership) quickly earned him a position far from the Latter Day Saints' heroic limelight. Non-Mormon authors, starting with Eber D. Howe in 1834, gave Sidney Rigdon a fair amount of exposure in their writings. This early negative publicity came primarily in association with Rigdon's supposed role in composing the Book of Mormon, by redacting and supplementing a certain manuscript allegedly authored by the Rev. Solomon Spalding. But even the most hostile of anti-Mormon writers began to shorten their chapters dedicated to Rigdon after one of Spalding's manuscripts was recovered in Hawaii in 1884. Beginning at about the turn of the century, most investigators of the Spalding claims for Book of Mormon authorship increasingly reported in their books and articles that it seemed unlikely that a Spalding-Rigdon literary connection could have resulted in the production of Smith's "golden bible." Following the appearance of Fawn Brodie's Smith biography in 1945, the reading public lost its previous interest in Sidney Rigdon. 02. Whitsitt's Unpublished Biography of Elder Rigdon: While most of the biographers and historians reporting on Mormonism near the end of the 19th century were relegating Rigdon to the scrap heap of the past, two or three interesting exceptions to this trend managed to gain a brief audience. One such writer was the Rev. Clark Braden, who in 1884 wrote and published a thick book documenting a series of debates he had with RLDS Elder Edmund L. Kelley. Another writer, whose views on Mormon origins closely paralleled those of Braden, was the Rev. William H. Whitsitt, second President of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky. Undaunted by the Spalding literary discovery in Hawaii and subsequent revisionist theories for the origin of Mormonism, Whitsitt relentlessly reinforced and extended Eber D. Howe's original thesis of Sidney Rigdon having been the real author of the Book of Mormon and the principal co-founder of the LDS Church. Whitsitt's extensive research into this subject enabled him to write a hefty biography of Elder Rigdon during the early years of the 1880's. He had nearly completed the work, entitled: "Sidney Rigdon, the Real Founder of Mormonism," when the discovery in Hawaii was made, but the biographer was able to fit the new information into his complex explanations regarding Mormon beginnings and doctrinal evolution. He completed his opus the following year. Subsequent events in Whitsitt's life directed his interest away from this particular biography project and he seems to have made no great efforts to get the work ready for a publisher. He tightened up his prose, extracted a section for separate publication, and inserted some new material here and there into the text during the period between 1888 and 1890, but the results remained unpublished. Practically all the publication resulting from Whitsitt's labor in this work is encompassed in a few short pages on Mormonism in John F. Hurst's 1892 Short History of the Christian Church, Samuel M. Jackson's 1891 Concise Dictionary of Religious Knowledge and Gazetteer, and Whitsitt's own 1888 Origin of the Disciples of Christ. The verbose and uneven manuscript prose resulting from Whitsitt's last attempts in editing the Rigdon biography endure today as a largely forgotten, badly outdated, and lamentably unpolished attempt to "expose" Mormonism. Considering the obvious time, effort. and skillful construction Whitsitt invested in this project, it is a shame that his limited access to primary sources (coupled with an inability to curb self-defeating rhetoric) kept him from delivering the definitive reporting that might have interested a major publisher of his day. Even the casual reader of this massive volume will probably come away from its reading with the feeling that the author jumped upon his literary hobby horse and rode off in three different directions all at once. The book attempts to provide a history of Smith's Church of Christ, an innovative explanation of that church's sacred books, and a detailed biography of one of its primary early leaders, all in one text. While Whitsitt's book certainly contains a great deal of insightful exposition and commentary on the Mormons' history and scriptures, it does not consistently elucidate Sidney Rigdon's life well enough to provide the reader with a definitive biography. Even F. Mark McKiernan's thin and problematic 1971 Sidney Rigdon... accomplishes its biographical purpose more effectively than does Whitsitt's heavy tome. The writer would have done better had he entitled his work "The Real History of Mormonism," and left out much of the personal information he compiled on Sidney Rigdon and the Book of Mormon. Had he done that, the result would have probably been publishable in the same way that his excerpted section on the Disciples of Christ was publishable as a modest, stand-alone volume in 1888. It is also a pity that Whitsitt did not enlist a knowledgeable editor to carefully partition and revise his manuscript material. Such an exercise of the editorial pen might well have produced a set of shorter and more readable volumes on early Day Saintism. Among that series he could have placed his exposure of Mormon origins and personal explication of the Book of Mormon as serviceable volumes in their own right. Whitsitt made passable use of primary and secondary sources available outside of Utah in the 1880's. He inspected documents, conducted interviews, compiled information from most of the major published sources (primarily anti-Mormon works), and delved into the Saints' own publications for certain facts and quotes. But despite his effort at gathering such necessary information, Whitsitt the researcher tended always to swallow anti-Mormon assertions whole, reserving his most strenuous application of critical examination mostly to those things the Mormons themselves had to say. This methodology betrays utilization of a personal double standard on Whitsitt's part, and his reliance upon this subjective bias continually impaired his otherwise often commendable attempts at reporting important information and unique insights. Whitsitt's Sidney Rigdon biography is a book built rather like the rotund Rigdon of later years: it is thin at the top and bottom and obese in the middle. The author was unable to compile anything like a trove of revealing facts and stories regarding the young man. Most of Whitsitt's contribution to knowledge in that area comes as a result of his postulating various details in the little-known relationship shared by Sidney Rigdon and the Baptist reformer Alexander Campbell. Some of his speculation regarding Rigdon's equally intriguing (and even less known) friendship with the Pittsburgh printer Jonathan H. Lambdin may eventually prove reliable, but Whitsitt was unable to supply the documentation necessary to demonstrate where such speculation can be accepted as reliable fact. The content of the biography again becomes noticeably thinner following the end of the Missouri period in early Mormonism. Here Whitsitt's inability to put some meat on the bones of his Rigdon chronology is less excusable. He simply runs out of creative steam during Nauvoo era and presents a two dimensional First Counselor in the Church Presidency who lacks both a clear motivation and any real ability to capture the reader's interest. Whitsitt must have found the detailed documentation of Sidney's final years to have been a near-impossible task. Being unable to provide his readers with the final years of the Rigdon story, the biographer simply let his previously energetic reporting peter out into a few sketchily expressed personal opinions at the end. Whitsitt researched and wrote other historical books and their published contents demonstrate that he was not ignorant of the historian's craft. Had he better developed and applied the insight and skill necessary to an accomplished historian, the Louisville professor might well have tied up the loose ends of the story with a better ending than the one offered in his manuscript. Whitsitt essentially leaves Rigdon's long post-Nauvoo life unrecorded and ends the without the enlightening summary the reader might expect in a major historical study. The book is not only an unpublished work; in several respects is also an unfinished one. Unfortunately (for Whitsitt) the place of Mormonism in American religious and social history remained largely undefined and unresolved as the 1880's were drawing to a close. The author had the misadventure to discontinue his research and writing just as the denouement of the national battle against Mormon polygamy and the related quest for Utah statehood was beginning to play itself out. Had Whitsitt gone back and finished his manuscript from the personal perspective and historical hindsight available to a writer on Mormonism at the turn of the century, his literary product might have turned out something like William A. Linn's roughly contemporary book on the Saints. Even though Linn tried one last time to tell the old anti-Mormon "Mormon History," Sidney Rigdon had died a decade before, forgotten by nearly everyone. Both Rigdon's story and some brief citations of Whitsitt's views concerning him are to be found in Linn's great compilation, but they are the fading ghosts of a fading century. No author would attempt to re-write Linn's span of history for another three generations, and in the meanwhile Fawn Brodie's 1945 book thoroughly quenched any lingering interest the reading public may have had in Joseph Smith's earliest associates in the church leadership he eventually came to dominate. 03. Structure and Content of the Whitsitt Manuscript: The manuscript biography of Sidney Rigdon, as it now sits on the shelves of the Library of Congress, is comprised of something over 1500 typewritten index cards, affixed two to a page on letter-sized sheets of stationery. The cards run in number from 1 to 1306 (numbers 26-126 range were removed in 1888) with many ancillary cards inserted (upon which Whitsitt appended a series of textual additions bearing alphabetized letters supplemental to the numeric designation of the preceding original card) at various points in the manuscript. Were the book published today as a typical hard cover edition, duplication of its contents would probably require a little over 1000 printed pages. Whitsitt's compilation follows the orthography and structural style of Remy & Brenchley's 1860 work and is divided into five "books," labled as follows: Book the First: Birth and Breeding Book the Second: The Baptist Period Book the Third: Disciple Period Book the Fourth: Mormon Period Book the Fifth: Sidney's Life After His Expulsion From the Church The first book is really nothing more than a short prefix to Book the Second. It consists of five pages of information on Rigdon and his family prior to May of 1817 when Sidney joined the Peter's Creek Baptist church, located in what are now the southern suburbs of Pittsburgh, PA, Whitsitt lacked access to most of the preserved records relating to Rigdon and his family and this fact probably explains the paucity of information set forth in this brief introduction. Whitsitt was unaware of the Rigdon family's English origins and guessed them to be Scotch-Irish. He was also unsure of the religious affiliation of Rigdon's parents. While a glance at the May 1789 "subscription paper" for the construction of the Peter's Creek Baptist church would have told Whitsitt that both Sidney's father, William, and William's brother, Thomas, were Baptists, the professor's researches into such subjects did not reach that level of primary documentary inspection. Also, the biographer's notion that Rigdon did not suffer from "mental derangement" only reflects the state of physiological knowledge in his day. In a modern examination of Rigdon's actions and religious pronouncements, such as that offered by his modern biographer, Richard Van Waggoner, can allow considerable leeway for the probability that he suffered from life-long bouts with mental illness. Whitsitt is no doubt correct in stating that Rigdon did not reside within the city limits of Pittsburgh during his youth. But a more careful examination of the man's interests and associations should have alerted Whitsitt to the likelihood that the youth delighted in frequent trips to the nearby frontier population center. The lure of the city's book shops, schools, churches, libraries, and debating societies must have exerted a strong attraction to the bookish and "lazy" (in terms of devotion to farm labors) young Sidney Rigdon. The second book provides Whitsitt's attempt at descripting Rigdon's interactions with the Baptists of western Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio. Here we see the picture of young Rigdon discovering a taste for a literalistic brand of Christian primitivism and a desire for the relative life of ease and comfort ehich might be had in becoming a frontier clergyman of that era. Whitsitt's thesis is that Sidney Rigdon very early fell under the reformist influence of Alexander Campbell, who was then living in the adjacant county and developing the doctrines of the Disciples of Christ religious restoration movement. In Whitsitt's view, Rigdon became something like an undercover Campbellite and a secret agent in promoting Campbell's plans for co-opting or capturing the leadership of Baptist churches in western Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio. The Baptist seminary president's opinion of Alexander Campbell is, if possible, even lower than his frequently expressed hatred for Sidney Rigdon, Joseph Smith, and the Mormons. Perhaps this view is to be expected in Whitsitt, as the congregations he saw being "perverted" into Campbellism and Mormonism were of his own denomination during a period when Baptist orthodoxy and cohesion were under attack "out west. Whitsitt saw Alexander Campbell as a vulgar literalist who preyed upon vulnerable Baptist communities by offering them a return to the original beliefs and practices of the earliest Christians mentioned in the New Testament. Whitsitt spends an inordinate amount of effort in describing the evolution of a certain strain of Christian primitivism from the Glassite Scottish seceders down to the Campbellites, Sidney Rigdon's Ohio congregations, and the first Mormons. In 1888 the writer removed a good deal of this section of his work and saw it published separately as Origin of the Disciples of Christ . . . 04. Whitsitt's Main Theory The third and fourth books of Whitsitt's works deserve chapter-by-chapter summaries and commentaries, the contents of which would necessarily extend far beyond the scope of this limited book review. These two portions of the manuscript comprise well over three-quarters of its total volume and contain just about all of the references used to establish and explicate Whitsitt's central thesis that Sidney Rigdon originated the Mormon Church as an outgrowth of his own peculiar brand of Campbellism. Whitsitt's theory is well summarized in the Preface which follows the opening title page to his manuscript book: Though the literature of Mormonism is extensive, no author has yet undertaken to investigate the Sacred Books of Mormonism with any degree of patience and system. Laborious and learned students have merely skimmed the surface of the Book of Mormon and the Book of Doctrine and Covenants. This is an omission which I have made it my task to supply in the present volume.As an adjunct support to his thesis of the Rigdonite origins of Mormonism, Whitsitt provides a bare-bones recitation of the Spalding Authorship Theory for the Book of Mormon. He informs his readers that he would have rather not had to introduce this problematical element to his biography, but believes that it shows where and how Mr. Rigdon came up with the basic narrative for the Book of Mormon story. Beyond this Whitsitt shows very little interest in Solomon Spalding, his life, ideas, or writings. While Whitsitt had access to the Spalding manuscript discovered in Honolulu by the time he was putting the finishing touches on his Rigdon biography, he had so little interest in and regard for that production that he barely allows himself to add a few short notes regarding its possible relationship with the Book fo Mormon. Whitsitt's book four takes up seemlessly where book three leaves off and there he primarily uses the Kirtland, Missouri, and early Nauvoo Mormon history to demonstrate how he sees the Latter Day Saint church and doctrine developing under the increasing theocratic leadership exercised by Joseph Smith and some decreasing theological input from Rigdon. The final book is a painfully short and inadequate attempt on Whitsitt's part to wrap up his biography and come to something like a conclusion. 05. Whitsitt's Book of Mormon Theory: Looking briefly back at book four of the Rigdon biography, we can see there developed and reported Whitsitt's thesis that an original Spalding narrative was re-worked, abridged, supplemented, and redacted into a radical Campbellite document which provided a new scriptural basis for Rigdon's departure from the latter day miracle-denying doctrines of Alexander Campbell. From his study of the Mormon texts (primarily the Book of Mormon and early sections of the Doctrine and Covenants, Whitsitt attempts to methodically explain both a hidden portion of Rigdon's personal life and the true origin of the earliest Mormon practices and teachings. Rather than get into a point-by-point examination of what Whitsitt has to say on these matters, I'll provide an excerpt from his own summary of this portion of his book. The following was printed in the 1891 edition of Jackson, Samuel M. Jackson's Concise Dictionary of Religious Knowledge and Gazetteer: The Book of Mormon: 06. Whitsitt's Anti-Mormon Bias: Whitsitt generally provides the appearance of having attempted to write scholarly history. However, the patina of seeming objectivity does nothing to conceal the rock-hard prejudice evident on nearly every page of his attempt at writing Mormon history and biography. Consciously or unconsciously Whitsitt appears to be attempting to outdo Howe, in casting epithets of derision upon Joseph Smith, jr., Sidney Rigdon, and the other early Latter Day Saints. The erudite Southern Baptist gentleman sometimes defeats his own purposes and ends up writing a story that induces more sympathy for the Vermont Yankees (the Smiths), turncoat apostates (Rigdon's Disciples), and some uninvited carpetbaggers (the Mormons in Missouri) than they do the righteous indignation Whitsitt wished to arouse. Curiously he extends this name-calling to Solomon Spalding and others, whose stories Whitsitt barely knew. He clearly thought that writer Ellen E. Dickinson was out of her league in trying to write history in a man's world. Clearly the seminary president was living in a world of his own imagining, where only he himself and perhaps a few educated co-religionists had the intellect and proper spiritual training to discern vulgar, non-Baptist delusion from sublime Whitsittite truth. Many other anti-Mormon books of this period were also written in the same hostile and derogatory language Whitsitt employs. What makes his defamatory derision particularly noticeable is his attempt to marry personal prejudice with scholarly methods and graduate-level vocabulary. The result is a sad and incongrous setting of interesting historical fragments in a matrix of disagreable finger-pointing and condemnation. Even if a few of Whitsitt's singular explanations regarding Rigdon, Smith, the Saints, and their holy book are partly true, the writer is never able to let go of his own petty prejudices long enough to produce the sort of objective, scholarly reporting which might significantly further our understanding of Mormon origins. The manuscript for his book is now almost entirely out-dated and languishes on the back shelves of a Library of Congress storeroom, unnoticed and unread. 07. The Value of Whitsitt's Work: This "untold story" of Sidney Rigdon and Book of Mormon origins includes a number of detailed, singular explanations for motives, events, and outcomes during the founding and early spread of Mormonism. Once these conjectures have been at least partially severed from Whitsitt's pervading sarcasm and derision, their contents probably deserve more attention from the academics than they has received to date. Both F. Mark McKiernan and Richard S. Van Wagoner made some minor use of Whitsitt in compiling their own biographies of Sidney Rigdon, but practically no one has written on the topic of the seminary president's unique research and theories. Whitsitt's statements on form and source criticism represent some of the most meticulous theorizing regarding Book of Mormon origins ever set down on paper. Whether they are right or wrong, they might have provided a useful point of departure for further investigation and discussion of these topics. But, since Whitsitt was unable to find a publisher for his sadly flawed work, both the loyal defenders of Lehite historicity and the hostile critics of the Mormon book have missed discovering this extensive mother-load of semi-scholarly speculation on Mormon scriptures. At the very least the Book of Mormon form and source critical-analyses set forth by Whitsitt should be addressed by some competant scholars of that book and of historical-critical scriptural studies in general. No doubt some of Whitsitt's purported findings in this area could be easily refuted by properly educated investigators and commentators. But, beyond study for the purposes of refining Mormon apologetics, Whitsitt might also be studied to see if his findings offer any real insight into has the Book of Mormon text is structured and how the internal relationships of that literary structure may have come about. Finally, Whitsitt deserves a chapter in any future study of anti-Mormon writings and publications. Because his work has lain unnoticed for so many years, its contents probably had very little influence upon the anti-Mormon works of the 19th and 20th centuries. However, given some much-needed editing and updating, the Rigdon biography may significantly impact the 21st century writings set forth to oppose prevailing views on Mormon origins. Some attendees of the October 1998 LDS General Conference were confronted with handbills touting the merits of Whitsitt's history. At the same time, in similar hand-bills distributed in Salt Lake City, well-known anti-Mormon writers Jerald and Sandra Tanner were being accused of ignoring Whitsitt's contributions to the anti-Mormon movement. It would be rather ironic if Whitsitt's lasting legacy is that of being an object of contention among the attackers of the Latter Day Saints and their religion. But, even if that becomes his only significant contribution to 21st century Latter Day Saint studies, we should all probably take a look at what he had to say over a century ago. (additional comments forthcoming) |

Return to top of the page

Return to: Beginning of 1891 Book | J. &. S. Tanners' Anti-Mormon Forgeries

Sidney Rigdon "Home" | Rigdon's History | Mormon Classics | Bookshelf

Newspapers | History Vault | New Spalding Library | Old Spalding Library

last revised June 8, 2010