|

THE COPPER MINES OF EDOM

--==( O )==--

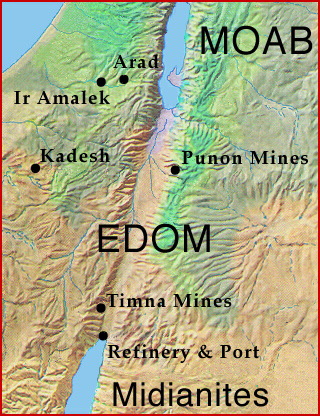

Detail Map of Southern Palestine (Early Iron Age) ARAD, IR AMALEK, AND EZION-GEBER

In his recent book, Living on the Fringe (Sheffield Academic Press, 1995), Israeli Archaeologist Israel

Finkelstein has demonstrated convincingly that "copper production might have been a crucial factor in the

sedentarization" of this region's desert peoples in early Bronze Age, and again in the early Iron Age (p 100ff).

In the earlier period the ancient walled town of Arad owed its existence and local power to control of the area's

trade routes. If the Arad people didn't actually control the mines, they at least controlled the copper trade with

Canaan, and perhaps with Egypt. After a period of decline in town life later in the Bronze Age, a similar situation

arose again around the beginning of the Iron Age, but this time with the Amlekites in control of the local trade

routes.

While most of the copper trade probably joined the flow of spices and other exotic items up from Arabia and

into Canaan, along the inland trade routes, some exchange with Egypt may have also been carried out via the

Gulf of Aqaba. At the site which would later become Ezion-gezer under the Israelite monarchy, an ancient

refinery turned copper ore into the pure metal. Although tin is not available locally, other metals may have

been combined with copper here to from alloys related to bronze. The location of such a complex so near the

shores of the sea indicates that Egyptian ships must have put into port here to pick up refined copper and metal

products. Exactly when the Egyptians first appeared is unrecorded, but by the early part of their 18th Dynasty

they controlled the "King's Highway" through Moab, Edom, and the Sinai. This would have given Egypt de facto

control over the Timna copper mines, even if the Empire's soldiers and priests didn't arrive in significant

numbers until after the Amarna era.

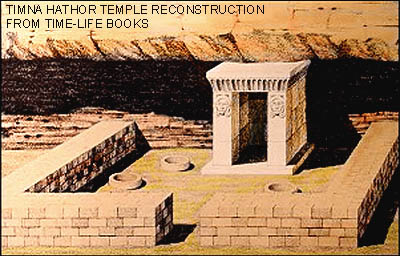

The Timna temple was a rather simple structure, compared with its older sister at Serabit. The fact that it has a layout more common to Syro-Palestinian temples than any Egyptian counterparts may indicate that Nile valley architects and skilled builders were in short supply at Timna. It may also indicate that, unlike the Serabit El-Khadim shrine, it saw few of the great Egyptian mining expeditions sent out to the Sinai to gather turquoise and copper ore. This brings up the probability that most of the worshippers at Timna were unlikely to have been Egyptians. It is even possible that maintenance and safeguarding of the shrine was left in the hands of local people, under the direction of relatively few Egyptian priests. If this were the case, then the local population came to venerate the site to the point that they felt compelled to maintain a shrine there after the foreigners had departed the area. The "Midianite" tent-shrine erected over the ruins of the Hathor temple did not continue the Hathor cult, but it almost certainly carried on the tradition that Timna was sacred ground and that certain rites should be conducted there. Since nearly nothing is known of "Midianite" religious beliefs it is impossible to know how much, if any, of the Hathor cult traditions were carried over into their activities at the shrine. It may be that at least a few fragments of the Egyptians' prayers, songs, and festivals were preserved here into the Israelite period. Return to Hathor in Southern Palestine |

return to top of page

The Sistrum in the Sinai | Hathor Home Page | Dale R. Broadhurst Home Page

last updated: Feb. 1, 2006