THE SISTRUM IN THE SINAI:

Essays on Hathor and the Biblical Exodus

Hathor "Naos Sistrum" and Satellite Photo of Eastern Egypt, Sinai and Western Arabia

|

Was Miriam a Hathor Prophetess?

--==(O)==--

Now, your next assignment is to compose a short mental essay summarizing the events in the text you just read. Forget anything else you think you know or have heard about the famous Israelite crossing of the Red Sea and just stick with the mental impressions you received from reading verses 3-18 of the story.

--==(O)==--

Even after many centuries, the words strikingly convey the feelings of an awestruck and joyful people who have just experienced a collective miracle -- a miracle of salvation that is transforming them into an entirely new people. But these ancient words are also striking in what they do not convey. Apart from probable later insertions (in verses 2 and 19), there is no mention here of the leader Moses or of most of the details familiar from the "Israelite exodus" or the "wilderness" setting. These kinds of story elements can be found throughout the surrounding prose narrative, but they are missing from the poetry. All is wonder and celebration in the verse section: there is no attempt to convey orthodox explanations or carefully crafted doctrines. The picture presented by the poetic fragment is historical, at least in the sense that it is non-mythological (YHWH is already a god moving with the people through time and space -- his miracles occur within the "real world"). However, not much factual historical or geographical information is to be found in these passages. Only the mentioned presence of an unnamed "pharaoh" tells us that the enemy was Egyptian. Only the references to chariots and to ancient Near Eastern peoples give clues as to provenance of the remembered event. The god being praised in the poetic fragment is clearly the same YHWH who is spoken of in the narrative, but, in terms of chronology and theology, he has yet to reveal himself and his Sinai covenant to the people he is saving. Given this understanding of time and place, there are some apparent contradictions here: this god is spoken of in post-covenant terms and the mountain of his residence sounds more like the Palestinian Zion than the wilderness Horeb. The story told in Miriam's song may date to the time traditionally assigned to the Israelite exodus, but its language probably comes from the earliest days of the Israelite monarchy. Whether the preserved textual fragment is a re-writing of an actual pre-conquest song, or a liturgical piece first composed a few centuries later remains unclear. Miriam's unexplained activities in praise of YHWH are perhaps a little puzzling to the modern student. This especially becomes the case when the snippet of narrative mentioning her is moved to the beginning of the piece and read as an introduction to the song, rather than left in its orthodox context within the larger Red Sea crossing epic. If we look at the "Miriam song" and the thread of "Miriam narrative" together, from this revised perspective, we naturally begin to ask questions about what really happened during the archaic episode: how did this obviously important, age-old oral tradition of "the prophetess" come to be embedded within the venerable Moses story? Why was it that the creation of this particular celebrative song has been credited to Moses?

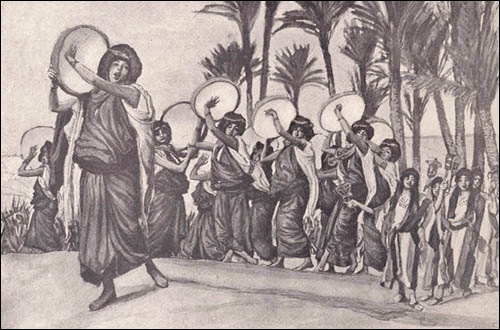

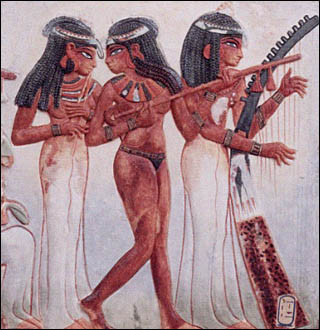

Nothing is said of Yahwistic prophetesses in the Torah, apart from this single reference to Miriam. Attempts to explain away the term as meaning nothing more than the female consort or relative of a male prophet seem unconvincing. On the other hand, back in the Egypt Miriam had just left, the term "prophetess" would have been equivalent to "priestess;" so perhaps this is the word's origin. If so, it provides an unsettling problem for Israelite ecclesiology: outside of the Torah we can find a "prophetess" or two, but nowhere in the Hebrew scriptures do we hear of Yahwistic "priestesses." The term is germane to sacerdotal positions within the old Canaanite religion, but not to the biblical Israelite religion. That having been said, it must be admitted that we know very little about the origins and earliest development of the Yahwist cult in southern Palestine, the Negev, and the Sinai. In prehistorical times that obscure faith may have indeed held a place for priestesses as well as prophetesses. The Miriam spoken of in the exodus story seems to have had no reservations about bursting forth with a hymn of praise to the largely unknown god of a newly formed "underclass" nation of wilderness wanderers. The modern reader of the story gets the impression that the musical praise and celebration carried out under Miriam's leadership was a religious exercise inherent to her official role and a practice in which she was already experienced and well skilled. And, although she is depicted in the story as singing to the women of the newly born Israelite nation, it is obvious from the text that her song of praise is directed to YHWH through the public singing and dancing. This is not simply the everyday social activity of a group of ladies getting together to entertain themselves or to act as cheerleaders for the nation's warriors. The event depicted is clearly some kind of established cultic activity led by a prophetess (or priestess) who possesses considerable religious authority in her own right. Rather than being struck senseless with amazement at YHWH's mighty acts of salvation, the Israelite women follow Miriam in a special form of cultic worship. It seems inexplicable that the women have their own percussion instruments within reach and already know how to use them in ways appropriate to the worship of a divine being. There is no hint in the text that this special kind of singing and dancing was a new form of religious expression or that the women needed to be trained in some new activity previously foreign to their socila behavior. We might be forgiven in our wondering at this point whether they might even have been a trained musical troupe, fresh from an Egyptian temple, where some women traditionally acted out divine dramas and engaged in consciousness-altering rhythms and movements. But, if this explanation of the event has any merit, how could these same women have been trained temple dancers and Semitic refugees, all at the same time?

Certainly the Canaanite cousins of the "children of Israel" saw much advantage (and no harm) in worshipping gods and goddesses highly reminiscent of those whose religion originated in the Nile Valley. As they departed from Egypt, according to the biblical story, the monotheistic YHWH was a god new to the refugees -- a replacement for (or new understanding of) the El or their ancestors. Even if no faithful daughter of Abraham carried a sacred Hathor sistrum rattle with her into the wilderness, some women in the "mixed multitude" departing Egypt must have. And, when the time came to offer up praise unto YHWH, their rattles and tambourines were made good use of. If Miriam really was a leader of a band of Hathor worshippers fleeing Egypt in the days of the exodus, she was no Asiatic bondwoman, born into the tribe of Levi. While priestesses (prophetesses) of Hathor had been common throughout the Two Kingdoms of the Nile Valley during earlier times, they had become a rarity by the time of Miriam and of the Israelite exodus. Female chanters, musicians, and dancers were still employed by the state cults in Egypt during the New Kingdom, but, in the period of the famous Eighteenth Dynasty, the important female officials in the Hathor cult would come almost entirely from the ranks of royal family. A Hathor priestess in the time of Amenhotep III or Ramses II would have been a blood relative of Pharaoh himself. This fact raises some interesting possibilities and problems in the case of Miriam the Prophetess.

--==(O)==--

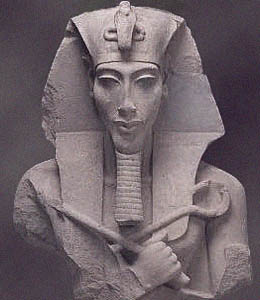

The time of the biblical exodus is generally represented as falling somewhere within the lengthy dominion of the Eighteenth Dynasty in Egypt -- perhaps as early as the reign of Amenhotep III, but certainly no later than the reign of Ramses III, when the nation of "Israel" is first carved into and Egyptian monument. Between these two pharaohs came the royal rule of enigmatic, larger-than-life kings like Akhenaten and Ramses II -- at some point in these turbulent times Miriam fled Egypt. Why? With whom? To where? What was the overlap between the religious practices and theological understandings Miriam and her people brought with them out of Egypt, and those of the Midianite and Kenite worshippers of YHWH living in Sinai and adjoining areas? Who were Moses and Aaron: how were they related to Miriam? Did the Semitic refugees of the "exodus" number women among their religious leaders? And, if they did, when and how were these female officials first excluded from the Mosiac Torah and its Levitical priesthood? --==(O)==-- Unless otherwise stated, all text and graphics by Dale R. Broadhurst |

There's much to consider in taking an oblique step from the known biblical territory into the hidden realms of Hathor. If you wish to follow this faint trail in the sands of the Sinai -- left ages ago by mysterious sistrum-shakers of Hathor -- here are some encampments along the way: |

return to top of page

Hathor Home Page | Dale R. Broadhurst Home Page

last updated: Feb. 1, 2006