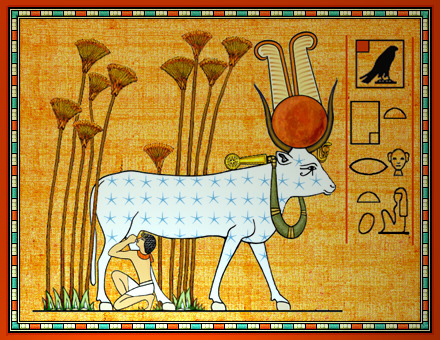

THE ORIGINS OF HATHOR

In the Primal Marsh Hathor Protects and Nourishes the Horus-prince

(click for detail of Deir el-Bahri shrine wall relief adaptation)

|

THE GODDESS WITH NO NAME The ancient Egyptian goddess Hathor (Hat-hor) might well be called the "Divine Lady of a Thousand Names." A list of her major titles would easily fill more than a couple of pages of small print in any history of religions text. On the other hand, the mysterious goddess might equally be called the "Lady of No Name," for none of those many titles was a personal name in the sense that Sarasvati, Diana, or Amatersu are female names. How could one of the most popular and enduring institutions of the Two Lands have been a divinity with no name?

Part of the answer to this question can be found in the fact that the Egyptians were reluctant to mention the

personal names of some gods, preferring rather to use their titles when speaking of them. Another reason can

probably be traced to the title Hat-hor (house/temple/womb of Horus) being an artifical construction of the Old

Kingdom Ra/Horus priesthood. It may well be that this particular title was purposely adopted as part of a plan

extend Ra/Horus propaganda and to obscure the goddess's true origins. As the "house" or mother of Horus the ancient

goddess of a hundred countryside shrines was brought into alignment with the religious orthodoxy of Ra/Horus divine

solar kingship. The Egyptian ideas of divine kingship and sun-gods can be traced back to predynastic times but they

only became united into a single state dogma some time after the Two Lands were united. Prior to Old Kingdom days

Horus was a local sun-god of the Per-Wer shrine in Hieraconpolis and Ra was a similar local divinity downriver in

Heliopolis. But who was the sky-cow goddess Hat-Hor and how did she become the mythological mother of Horus?

Since Hat-hor was the Sky Goddess as well as the Cow Goddess, a search among the other Egyptian sky-goddesses might prove useful. Besides Nekhbet there were Mut, Nut, and a host of lesser female divinities associated with the sky. But, again, none of these changed her name and became Hat-hor. If we look deeply enough into Egypt's early religious texts we can even find cow-goddesses with sky-goddess aspects and sky-goddess described in bovine terms. Clearly these two major Hat-hor aspects, dating to her pre-Horus cult days, were not unique to any one Egyptian goddess. The very old goddess Au-Set (Isis) overlaps and parallels Hat-hor in many areas (sky-goddess, cow-goddess, tree-goddess, mother of Horus, etc.), but Au-Set is a special case, having absorbed much of this overlap during the development of the Isis-Osiris cycle, after the Hat-hor cult was already well established. To uncover Hat-hor's true origins we must look to a much earlier period for information.

One archaic element of Hat-hor iconography always ran counter to the longstanding Egyptian practice of avoiding human and godly frontal views in two dimensional art. In her human and semi-human forms Hat-hor is one of the very few Egyptian gods who looks the viewer directly in the eye. Bes, Bat, protective cobras, and perhaps a couple of other very ancient deities share this remarkable trait, but Hat-Hor was famous as the House of the Face. Again, this fact summons up prehistoric images of bovine heads or skulls mounted on walls, posts and lintels -- set up Texas ranch-style, horns on the wall for everyone to see. The magic and sense of familiarity associated with this face-to-face frontal view was preserved in Egypt down to Roman times. At Hat-hor temples worshippers could gaze directly into her compassionate face, even if their social or religious status allowed them to approach no nearer than the face-topped columns of the temple facade. Hat-Hor's prototype was born in the minds of stone age hunters as an Egyptian mother-goddess; she did not evolve into an earth-goddess with the coming of agriculture, but retained her sky qualities instead. And, in her earliest Horus-mother identification, she remained without a spouse. Later minds would conceive of an Isis and Osiris as Horus parents, but Hat-hor never fully evolved into any god's wife. These facts raise the possibility that at least some of her early devotees were members of matriarchal and/or matrilineal groups which had no problems worshipping unmarried female deities. Such archaic mother-goddesses tended to change or die out when powerful male sky-gods were established in other Ancient Near Eastern religions. They may have been more resistant in the hypothetical "female dominated" Nile Valley societies. Whatever the truth might be in such speculation, Hat-hor was seen from earliest times as the heavenly mother of the rightful tribal leaders. As such she invested these chieftains and kings with certain powers and the right to rule. It is likely that the earliest Nile valley male rulers from Kush to the Delta were dependant upon Hat-hor style goddesses to provide and maintain their right and strength to reign over their subjects. When this strength faded and was not renewed by the goddess the ruler was dismissed from his office or even eliminated. Hat-hor's role in pharaonic sed festivals grew out of these primitive leadership testing and power renewal practices.

With the development of divine solar kingship as a national institution and the growth in importance of "sun-city" Heliopolis, the original Hat-hor functions of the Hieraconpolis Horus shrine were transferred to the former city and its newer House of Horus temple. There all the king-making powers of the local Hat-herts were consolidated into a single state supported female divinity. Thus, even with the ascendance of Ra to the top of the national pantheon, earthly Horus-princes continued to visit a special shrine of the sky-cow mother-goddess to be invested as rulers of Upper and Lower Egypt. The major innovation was that only one king at a time was thus empowered and only one, unique goddess "gave him birth." The great Hat-hor of the Two Lands had come into being. The archtype behind all the regional Hat-herts became the tool of the state: no doubt she was still a dangerous genie, even within her new confines. While sky-cow goddesses remained very popular among the common people (particularly among Egyptian females), over the centuries the names and details unique to these local deities were gradually lost. In only a few localities did such details linger on into later times. Perhaps the best example of such a local divinity retaining some of her identity after establishment the state Hat-hor cult is that of the goddess Bat, the sky-cow protectoress of Hu and the seventh nome of Upper Egypt. The semi-human head of Bat (or some very similar sister goddess) may be seen depicted on the famous slate palette of King Narmer (from Upper Egypt where sky-cow goddesses were the nome deities in several areas). An emblem of Bat was also carved into the famous trinity statue of Fourth Dynasty King Menkaure, Hat-hor, and the Hu (Diospolis Parva) protectoress. In this ancient masterpiece we can see the horned head of Hat-hor alongside the horned head of Bat. The major difference in the heads: Hat-hor's cow horns curve outward, while Bat's curve inward. The relationship between the regional goddess Bat and the Fourth Dynasty's Hat-hor is not a simple one, but it may not be far from the truth to say that Hat-hor was assembled out of a variety of attributes originally belonging to Bat and her cousins, the local sky-cow deities. These insights may help shape our understanding of who Hat-hor was in her pre-Horus cult days, but we are left with many mysteries about her which may never be solved. For example: Exactly how did Hat-hor come to be associated with far off Byblos and its famous goddess at the very dawn of Egyptian history? Why did Hat-hor share so many attributes with the Mesopotamian cow-goddess Ninhursag? And why did Hat-hor worship fail to survive the Roman occupation while the closely related Isis religion spread across the Latin Empire? Perhaps some lingering fragments of the Hat-hor cult can still be found, tucked away in the archaic rituals of the Coptic Church (which still uses the ancient calendar and its Hathor month in the liturgy), but we know less about how Hat-hor died than how she was born. Perhaps old goddesses, like old soldiers, never really die. They reside in the astral vastness and just fade away in our memories. Hathor essay and computer graphics by Dale R. Broadhurst |

return to top of page

The Sistrum in the Sinai | Hathor Home Page | Dale R. Broadhurst Home Page

last updated: Feb. 1, 2006