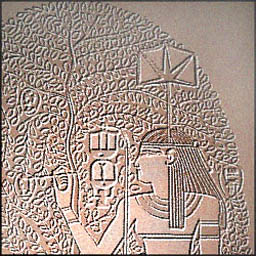

THE LADY OF THE SYCAMORE

Hathor the Tree-Goddess (from a tomb painting)

|

Hathor, Sycamores and the Sinai A TREE AS LOVELY AS A POEM Whoever it was who first said, "I don't care a fig for that!", made a major mistake in symbolism. Far from being something next to worthless, the age old fig tree and its fruit have been a boon to humankind from the beginning. For untold centuries weary Near Eastern travelers have rejoiced to see a fig tree in the distance. The presence of such a tree meant that fresh water was close at hand, along with a shady place to rest, and perhaps a handful of sweet fruit. Since such bounty was obviously the gift of a benevolent power, the people might also expect to encounter the protection and blessing of the local tree-spirit.

A number of tropical fig species grow in moist spots throughout the Fertile Crescent, the most well known being Ficus carica, the fruit of which can be purchased in grocery stores around the world. Less well known, but important to our study of Hathor is Ficus sycomorus, the sycamore fig. This species has the same general form as the common fig and, in its old age, can grow to be an impressive, stately monarch among the flora along the desert margins. It differs from the common fig in that its leaves are small and simply shaped, resembling those of the mulberry. Indeed, the two related plants are occasionally confused, with the sycamore fig being wrongfully called "the black mulberry." The fruit of the sycamore fig resembles that of the common fig, but grows in clumps of larger proportions than that of its cousin. (See the picture above for a stylized depiction of these blood-red fig clusters).

HATHOR'S TREE Trees have always been seen as something special in unforested Egypt and it comes as no surprise to learn that certain kinds of trees were venerated as sacred, life-giving plants. The sycamore fig was a particularly fitting candidate for tree-cult worship. It could grow some distance from the Nile, at the edge of the desert of death, but only did so in the presence of life-giving water. When this water came from an unseen, subterranean source, the presence of a sycamore fig must have appeared rather miraculous. The tree's life vs death symbolism was enhanced by the fact that it lost its leaves during the winter and appeared as a barren, lifeless object from a distance. A closer inspection might reveal some unpicked fruit remaining from the previous season's two or three bounteous crops, however. And this was joined in early spring by "the flowers of life"-- buds which became new green fruit even before the leaves returned. Like the winter evergreens and berry laden holly of northern latitudes, the sycamore fig was seen by Egyptians as bearing life in the midst of death. The tree, like Hathor herself, could be seen as a powerful symbol of that Divine Being which encompasses both life and death.Hathor entered the Egyptian state religion near the beginning of the Fourth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom, and from that time forward absorbed the attributes of a certain sacred sycamore spirit at Heliopolis (sometimes called the Giza sycamore). Just a short distance to the south she was worshipped at the Mistress of the Southern Sycamore at Memphis. By the reign of King Menkaure (c 2739-2722 bce) her titles had expanded to include "Mistress of the Sycamore in All Her Places" (i.e., all the nomes of the Two Kingdoms). Beyond these facts, we do not know exactly how the fig came to be associated with the sky-cow goddess. Since this tree was thought of as existing in the afterlife to provide nourishment to departed souls, goddesses such as Nut, Isis, and Saosis probably made their connection with the fig in a mortuary context. None of Hathor's earliest aspects seem to be associated with mortuary practices for the common folk, but as Goddess of the Giza Sycamore she would have performed afterlife functions for the pyramid-building kings. In time Hathor took on the identification of the tree-goddess who nourished the ba-souls of all the dead who entered the world beyond this one. Such nourishment was not mere earthly food and water, but rather magical "elixirs" and "airs" of renewal, necessary for celestial life. Another likely reason for Hathor's early identification with the tree is that fig leaves were used for medicinal purposes among ancient Near Eastern peoples and Hathor was very early thought of as the goddess of healing powers. A second identification possibility lies in the fact that Hathor was worshipped as the Mistress of Drunkenness and the fruit of the sycamore fig may have possessed some intoxicating or consciousness altering effects. Similar magic was seen in the related mulberry's blood-red fruit juice's power to enrage animals. As Mistress of Inebriety Hathor had dominion over all altered states of consciousness, not just alcoholic stupor; so it would be reasonable to connect her with an intoxicating or narcotic fruit. How the sycamore fig might have been prepared to produce such psychotropic effects is unknown today. No matter how the tree and its fruit came to be linked to Hathor, it can be assumed that, in certain instances, fig consumption was equated with eating the flesh and drinking the blood of Hathor herself. Since tomb paintings often show Hathor leaning down from the tree to pour out wine and offer bread to souls in the afterlife, an analogy with the Christian communion sacrament might be appropriate. Merlin Stone makes just such a comparison in pages 214-218 of her book, When God was a Woman (NY, HBJ, 1976). Here she also equates the sycamore fig with the forbidden fruit of the book of Genesis. Since the early days of rabbinical commentary readers of Genesis have tried to identify the common fig or sycamore fig tree with the biblical tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Stone follows this same pattern, stressing the sexual aspect of having a knowledge of good and evil. She also points out the connection between fig leaves and the genitals (an association also found in Mithraic religion). It is likely that devotees in some tree-cults covered or clothed themselves in tree leaves during special festivals. Such practices may have occurred in Hathor's tree-goddess worship. As for the modern development of this idea, the shape and size of sycamore fig leaves would not make them particularly useful as the "fig leaf" genital coverings attached to classical statuary. SEX, DRUGS, AND ROCK & ROLL Whether the Egyptian Hathor cult initiates used the sycamore fig as an hallucinogen or aphrodisiac will probably never be known. Cultists no doubt ate the fruit in a worship setting and the Hathor priests and priestesses would have frequently eaten goddess blest figs from temple offerings (along with milk from sacred cows and other holy victuals). It is possible that they experienced such meals as a kind of communion with the goddess and as a way of attaining some measure of her powers or attributes. And, it should be remembered, that as the goddess of fertility, drunkenness, and enchanting music, Hathor was something like the modern equivalent of a Mistress of Sex, Drugs, and Rock & Roll.ISRAELITES AND SYCAMORE FIGS Goddess iconography, mythology, and cultic practices passed back and forth between ancient Canaan and the Nile valley. While neither region fully adopted the beliefs and methods of its neighbor in this exchange, Egyptian ideas about the sacramental, revitalizing powers of the sycamore fig must have been known and understood in Canaanite goddess worship. In this context, the sexual implications pointed out by Stone would have taken on a particular significance in the eyes of the Canaanite's henotheistic cousins, the Israelites. The Genesis story of the forbidden fruit, the figs of "good and evil" in Jeremiah 24, and Jesus' cursing of the fig tree in the gospels are all best understood with a knowledge of the probable use of this fruit in the Canaanite cults. In the case of the Jesus pericope, the gospels probably half-conceal some obscure, messianic action which was part of the passion story and which demonstrated the Messiah's triumph over the sin which began with the eating of the forbidden fruit.The Israelites were no strangers to the common fig, sycamore fig, and mulberry (sycamine). They had their sycamore dressers (Amos 7:14), overseers (I Chron 27:18), and their fears of losing the precious trees (Ps 78:47); but by the time of Jeremiah, at least, the religious leaders no longer accepted any cultic use for the fruit. The promulgation of the Garden of Eden story was part of their strong attack on unorthodox practices and the sycamore fig was denounced as "the evil fig." ROCK-A-BYE HORUS, IN THE TREE-TOP Hathor was the goddess who gave birth to Horus and thus made the sunrise possible. From the Nile valley the Egyptians looked off to the eastern horizon each morning to see the physical demonstration of this sacred notion. Just past the horizon was the land of the underworld or the afterlife and at the boundary between that world and our own stood Hathor's gigantic sycamore tree, its roots in the earth and its branches in the heavens. Each day the sun-child was born and rose from the top of this tree to begin his godly transformation into Ra as he sailed up into Hathor's sky. In the upper branches of this tree the gods rested like birds on their perches. It was the desire of all devout Egyptians, from Middle Kingdom times forward, to join Hathor in her tree after death, to have their ba-souls perch themselves there among the gods. This was thought possible for those who had lived proper lives and whose good deeds had been recorded by the Goddess Sheshat on the leaves of the Heavenly Tree.

Sheshat, the Egyptian Celestial Librarian, Writes Upon the Tree of Heaven's Leaves SYCAMORES IN THE SINAI? From the latitude of middle Egypt the eastern horizon appeared to be somewhere out over the Sinai Peninsula. The BOOK OF THE DEAD speaks of "two sycamores of turquoise" between which the sun-god rose each morning. These otherworldly trees might be pictured as pylons or obelisks flanking the gate from the other world to the heavens of this world. Such imagery was popular during New Kingdom times and probably represents an evolution of thought concerning Hathor and her tree on the eastern horizon. Egyptian turquoise came only from the southeastern Sinai coast and Hathor had a special temple among those turquoise mines on the plateau which today is called Serabit el-Khadim. If New Kingdom Egyptians imagined two great turquoise sycamores growing out of the Sinai sands, their vision must have been symbolic rather than realistic. Fig trees would not have grown in the Sinai unless seedlings had been transplanted to some frost-free oasis and carefully tended for years. There were, no doubt, Hathor worshippers among the group of proto-Israelites who crossed the Sinai wilderness in New Kingdom times. Once they'd left Egypt, the only sycamores they might have seen in their journey would have been pictures in places like the Serabit and Timna Hathor temples. Only after crossing the hills of Judah or Ephraim would they have descended into warm, fertile lowlands where Hathor's tree might take root and grow. We wonder if among their murmerings for the leeks and onions of Egypt an occasional member of this wandering band did not cry out for a sweet, ripe sycamore fig, blest by the Goddess herself. text and graphics enhancement by Dale R. Broadhurst Hathor in the Sycamore" picture (from Tomb of Panhsy) courtesy of Chris King |

return to top of page

The Sistrum in the Sinai | Hathor Home Page | Dale R. Broadhurst Home Page

last updated: Feb. 1, 2006