Mormon Classics | Spalding Library | Bookshelf | Newspapers | History Vault

|

SIDNEY RIGDON

AMONG THE BAPTISTS HIS EARLY YEARS IN AND AROUND PITTSBURGH Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 |

|

Redstone Bap. Index: 1804-14 | Redstone Bap. Index: 1815-30 | Beaver Bap. Index: 1810-30

1824 Campbell's book | Greatrake's 1824 pamphlets | Campbell's recollections of 1823

1824 Walter Scott pamphlet | 1824 Alex. Campbell reply | 1825 Alex. Campbell pamphlet

1826 Greatrake tract | 1826 McCalla's tract | 1828 Campbell's reply | 1831 McCalla's book

1868 Memoirs of A. Campbell | 1874 Life of Walter Scott | 1875 Disciples on West. Res.

1904 Relation Baptists/Disciples | 1909 "Disciples in Pittsburgh" | 1919 Origin of Disciples

1931 Religion Follows the Frontier | 1948 Disciples History | 1952 Buckeye Disciples

2000 Knowles Diss. | Rigdon in Ohio | Rigdon Revealed series | Newspapers articles

|

Early Relation... of Baptists and Disciples by Errett Gates Chicago: Donnelley & Sons, 1904 |

|

|

Origin and Early History of the Disciples of Christ by Walter W. Jennings Cincinnati: Standard Pub. Co., 1919 |

|

|

Religion Follows the Frontier by Winfred E. Garrison New York, Harper & Brothers, 1931 |

|

Note: Entire contents copyright (c) 1931 by Winfred E. Garrison

Only limited, "fair use" excerpts are reproduced here

|

204 RELIGION FOLLOWS THE FRONTIER ... OHIO In Ohio, as already narrated, the beginnings were connected with the spread of Campbell's views among the Baptists. The church at Warren, for example, was founded as a Baptist church in 1803. Adamson Bentley, its minister from 1811 to 1831, was prominent alike in organizing it into a yearly meeting of Disciple churches. After Scott had rediscovered, as he believed, the principles of the ancient order, the church at Windham, Portage County, Ohio, was the first congregation organized de nova "upon the principles of the restored Gospel" -- on May 27, 1828, according to Hayden's Disciples in the Western Reserve (see also Scott's report in The Evangelist, April, 1838).By 1830, as we already know, the Baptist churches of Ohio had been largely permeated with the teaching of the Reformers, and both the Mahoning and the Stillwater associations had been completely taken by them. Almost simultaneously the Mormon church came into existence in the adjacent corner of New York and began its invasion of Ohio. Disciples and Mormons appealed to the same constituency and with some striking similiarities of approach, though also with some notable differences. EMERGING FROM THE PIONEER STAGE 205 Both based their appeal upon a plea for the restoration of a divine plan. The Disciple preachers became prominent leaders in Mormonism -- Sidney Rigdon, Parley P. Pratt, and Orson Hyde. Rigdon converted Pratt and Hyde to the Disciples position, and Pratt converted Rigdon to Mormonism. The transition from one camp to the other was abrupt in all three cases, but startling in Pratt's case. He preached one day as a Disciple and the next as a Mormon elder. Naturally they carried over with them many of the forms of thought amd much of the terminology to which they had been trained. The defection -- or conversion, according to point of view -- of these three preachers, carried many Disciples over into Mormonism. It is to be remembered that they had not been Disciples very long, and that among the followers of any new movement there is always a certain percentage of those who are temperamentally disposed to follow any new thing. Rigdon became associated with Joseph Smith in the First Presidency of the Mormon Church and was a claimant for the leadership of the organization when Brigham Younf secured it. Pratt and Hyde became "apostles." The Mormon historian, Roberts, considers the Disciples as forerunners of the Mormon gospel, and that Campbell and Scott were also (like Rigdon) "sent forth to prepare the way before the Lord." The Disciples did not think so. The rivalry between the two groups became intense. That the Mormons found among the Disciples, as Roberts says, "more who would listen to their teachings and a greater proportion who would accept the fulness of the gospel than in any other sect," did not improve their relations. Besides, the Disciples, being themselves rather outside the pale of denominational respectability, could not afford to jeopardize such standing as they had by letting pass unchallenged the assertion that they were in any way akin to this new and disreputable sect -- for both were disreputable and fanatical it was deemed, even before polygamy was introduced to render it altogether contemptible. The conflict 206 RELIGION FOLLOWS THE FRONTIER between Disciples and Mormons included several debates and at least one instance of mob violence with the latter as the victims, at Hiram, Ohio. But the Mormons passed on west, under the stimulus of persecution, and the Disciples recovered from the stigma of contact with them.... (remainder of this text not transcribed, due to copyright restrictions) EMERGING FROM THE PIONEER STAGE 207 (remainder of this text not transcribed, due to copyright restrictions) |

|

Disciples of Christ A History by Winfred E. Garrison and Alfred T. DeGroot St. Louis: Christian Board of Pub., 1948 |

|

Note: Entire contents copyright (c) 1948 by Christian Board of Publication

Only limited, "fair use" excerpts are reproduced here

|

[ 180 ]

Walter Scott was born in Moffatt, Scotland, October 31, 1796. Financial limitations -- his father was a music teacher who had ten children -- did not prevent him from getting a thorough classical education. He studied at the University of Edinburgh, and it is supposed that he took a degree; but his name was so common in Scotland that it is not possible to identify him with certainty in the university's records. In 1818 he came to America at the suggestion of an uncle who had a good position in the New York customs house. After spending nearly a year as an instructor in Latin in an academy on Long Island, he heard the call of the West and journeyed to Pittsburgh, where he arrived on May 7, 1819. There he became an instructor in a school conducted by a fellow countryman, George Forrester, who was also the leader of a small church of "humble, pious people, mostly Scotch and Irish" (Wm. Baxter: Life of Elder Walter Scott, p. 40). This was one of the many scattered "primitive Christianity" congregations which had sprung up under the stimulus of the ideas of Sandeman and the Haldanes. It is impossible to determine, from the existing records, to which of these strains it was most closely akin, and it makes little difference, for the impulse to reproduce the practice of the early church was common to them all, and the details of church procedure varied within each group. This Pittsburgh church practiced immersion and also the ceremonies of foot washing and the SCOTT AND THE NEW EVANGELISM 181 "holy kiss." The name locally given to it was "kissing Baptists." Scott, who had been reared in the Church of Scotland, was greatly impressed by Mr. Forrester's piety and by his passionate devotion to the direct study of the Bible as the source of religious truth. He became a member of this church. Forrester's withdrawal from the school, followed soon by his accidental death by drowning, left with Scott the responsibility for conducting the, school and shepherding the church. While wrestling with these duties and assimilating the ideas in the books of Glas, Samdeman, Haldane, and John Locke which he found in Forrester's library, Scott came upon a pamphlet that had been written by Henry Errett, father of Isaac Errett, and published by a New York City congregation of "Scotch Baptists" (the name generally given to the immersionist branch of the Sandemanians), who "held many of the views taught by the Haldanes" (Baxter, op. cit., p. 46). This tract was on the purpose and effect of baptism. It connected baptism so definitely with remission of sins and salvation that, in this view, it became highly questionable whether any of the unimmersed, regardless of their apparent possession of the fruits of the Spirit, could be "acknowledged as Disciples, as having made the Christian profession, as having put on Christ, as having passed from death to life." Scott was so stirred by this discovery that he closed his school and went to New York to further instruction from the church which had set forth this statement. He was frank in admitting that the visit was a disappointment, though he never said just why. Certainly he suffered no loss of conviction as to the importance of returning to simple New Testament Christianity. Baxter would give us to understand that he was disheartened to see the "sectarian" churches so indifferent to this program which seemed to him so axiomatic and imperative. One may be permitted to conjecture, in the light of his course thereafter, that Scott was discouraged by the pettiness of the program for carrying out the great principle more than by the reluctance of the whole Christian world to accept it instantly. This New York church was the one which only a little later, was having a discussion by correspondence with a similar church in Edinburgh is to whether the Scriptures commanded that the service of worship should be opened with a hymn or with a prayer. 182 THE DISCIPLES OF CHRIST While Scott was in this state of depression, there came a pressing invitation to return to Pittsburgh. It came from Mr. Nathaniel Richardson, a substantial citizen and an Episcopalian, who wanted him to be tutor to his son Robert and a few other boys. (This Robert Richardson became a professor in Bethany College and Alexander Campbell's biographer.) Scott accepted this call, but on his way he visited other congregations of restorers of primitive Christianity of the Haldanean persuasion -- at Paterson New Jersey at Baltimore, and at Washington. He was not heartened by what he found in any of them. SCOTT MEETS CAMPBELL Back in Pittsburgh, Scott resumed the care of the church while carrying on the teaching by which lie earned his livelihood. The little tutoring enterprise for fifteen boys grew, as soon as the limit was lifted, to a school with 140 enrolled. This was the golden age of private academies; there were no public high schools. Serious study of the religious questions in which Forrester had aroused his interest was also a part of Scott's daily program. Locke, Glas, Sandeman, and Haldane were still among his favorite authors, but the Bible was his basic material. Brooding upon this, he reached the clear conviction that the central and sufficient fact for Christian faith could be stated in these four words -- "Jesus is the Christ." Scott had advanced so far on the way toward a church with no other creed than this before his first meeting with Alexander Campbell in the winter of 1821-22. This was at a time midway between the Walker and Maccalla debates. The two young men -- Scott, twenty-five; Campbell. thirty-three -- were congenial from the outset. Campbell, with the start that his father had given human in the Declaration and Address, had gone farther on the road to church reformation and was more definitely committed to the goal of union. Scott, getting his impulse from the separatist groups, whose interest was solely in the exact restoration of the primitive church, had given little thought to the union of Christians; however, he was soon to make a contribution of such importance that without it there would probably never have been occasion to write a history of the Disciples.Within less than a year, after his first meeting with Scott, Alexander Campbell began to make plans for the publication of the Christian Baptist. It is said that the name was suggested SCOTT AND THE NEW EVANGELISM 183 by Scott. Campbell had proposed to call it " The Christian." But Scott, though not himself a Baptist, thought that the addition of "Baptist" to the name would increase its appeal to the denomination to which Campbell belonged and within which his ideas were beginning to gain currency. To the first volume of this magazine Scott contributed a series of four articles entitled, "A Divinely Authorized Plan of Preaching the Christian Religion." This was another step in defining the process by which one becomes a Christian. That matter had really been central in Thomas Campbell's original interest, for the conditions upon which one becomes a Christian must be identical with the terms of fellowship and constitute the basis of union. But attention had been diverted to the development of a complete plan for the restoration of the church on the primitive pattern, which, it was assumed, would be the necessary pattern of the united church; then to the distinction between the dispensations, which was useful in directing attention to the part of the Bible which gives information about Christian institutions and in putting aside misleading analogies with Old Testament practices; then to a more comprehensive study of baptism, including its design as well as its action and subjects. This was all very well, but it did not give an exact answer to the question, How do people get to be Christians? To that question Scott began to give attention in this series of articles, for, of course, a "divinely authorized plan of preaching the Christian religion" would be only a way of stating the divinely authorized plan of accepting it. The complete statement and application of Scott's "plan" had to wait until, four years later, he became evangelist for the Mahoning Association. But an important foundation was laid in these articles. The emphasis here was upon the nature of faith and the way in which it is produced. Scott wrote: Jesus having died for sin and arisen again to introduce the hope of immortality, the great fact to be believed, in order to be saved, is that he is the Son of Cvod; and this being a matter-of-fact question, the belief of it as necessarily depends upon the evidence by which it is accompanied as the belief of any other fact depends upon its particular evidence.... We shall. see by and by that to preach the gospel is just to propose this glorious truth to sinners, and support it by its proper evidence. We shall see that the heavens and the apostles proposed nothing more in order to convert men from the error of their ways 184 THE DISCIPLES OF CHRIST and to reduce them to the love and obedience of Christ.... In short, the apostles proceeded thus: they first proposed the truth to be believed, and, secondly, they produced the evidences necessary to warrant belief. This view of faith as the result of using ordinary intelligence, an act of which even sinful man is capable, and, as he calls it, a "matter-of-fact question" having to do with evidence, was far from being an original discovery with Scott. Many of the Reformers mentioned in this book had taken the same view. Thomas Campbell had hinted at it during his trial by the synod. It was fundamental in Alexander Campbell's theology. Stone had expressed it in early life, then apparently had forgotten it until he was reminded-indirectly by Scott. Back of these, John Locke had said the same thing, so clearly that perhaps all the others had learned it from him. Robert Sandeman generally (but not always) took this view, and in his Letters on Theron and Aspasio (4th edition, 1803, p. 252) he quotes from Locke's Reasonableness of Christianity: "The faith required was to believe Jesus to be the messiah, the anointed, who had been promised by God to the world." This was Scott's exact position as to both the object and the nature of faith. In his Christian Baptist articles, Scott Is specific purpose was to show that preachers should try to produce belief in the Messiahship of Jesus by presenting the evidence, instead of trying to induce a mystical state variously called an "assurance of pardon," or "assurance that Christ died for me," by emotional techniques, vivid pictures of the fate of the damned, and wrestlings to win the miraculous action of the Holy Spirit to bestow saving faith on a mourner already "convicted of sin." He was thinking his way toward an intelligent, effective, and scriptural method of presenting the gospel. During the next three years, until 1826, Scott remained in Pittsburgh, teaching and caring for the little church of "kissing Baptists" and contributing frequent articles to the Christian Baptist. Then he moved to Steubenville, Ohio, where be was a much nearer neighbor to Mr. Campbell. Describing the situation as it was in 1827, Scott wrote a little later: There were three parties struggling to restore original Christianity: the first of them calling themselves "the Churches of Christ;" the second calling themselves "Christians," and the third laying [sic] at that time chiefly in the bosom of the Regular Baptist churches and originating SCOTT AND THE NEW EVANGELISM 185 with the writings and labours of Bro. A. Campbell. To the first of these parties, up to 1826, belonged your humble servant, W. S. (Evangelist, April 1, 1832. [sic - 1833]) Scott's first group consisted of those independent churches, in Great Britain and America, which had received their impulse to restore primitive Christianity chiefly from Glas, Sandeman, and the Haldanes. The second was the "Christian" Church as he had seen it in Ohio, knew of it in Kentucky, and perhaps had heard of it in the northeastern and the southern seaboard states. The third was the Campbell movement, lying somewhat uneasily "in the bosom of the Regular Baptist churches." It may be noted that the common characteristic of these three, according to Scott, was their purpose to "restore original Christianity. "Union is not mentioned as an aim, though it may have been implied in the word "original." As a matter of fact, the stress upon union was at this time slight in any of the three. REFORM SPREADS IN OHIO Meanwhile, the spread of Campbell's views among the Baptists of eastern Ohio had made no little progress. This is indicated by some of the questions which, according to the prevalent custom, local churches sent up to the annual meetings of the Mahoning Association for authoritative answers. In 1823 came this question: "May a church which has no ordained elder observe the communion or administer baptism?" The answer was "No." Some church evidently doubted whether ordination conferred powers that a layman did not have, and perhaps resented the tendency of even Baptist ministers to form a clerical caste; but the association still stood by the clergy. In 1824 three questions were submitted which showed the ferment of new ideas: (1) "Is it apostolic practice for churches to have a confession of faith and a constitution besides the Scriptures? No answer. (2) "How were members received into churches which were set in order by the apostles?" The question was held over for a year, and then the answer was, "Those who believed and were baptized were added to the church." Nothing was said about requiring an "experience" and a favorable vote of the congregation, in the usual Baptist fashion. The rational, rather than emotional, conception of faith is certainly not excluded and seems even to be implied. (3) "Can associations in their present modifications find their model in the New186 THE DISCIPLES OF CHRIST Testament?" "The answer: "Not exactly." In 1825, the association was called upon for an answer to this crucial question: "Was the practice of the primitive church an exact pattern to succeeding ages?" The answer was, "Yes." Before this the church at Hiram had voted to discard its church covenant, constitution, and Confession of Faith and to take "the Bible alone" as its standard. Soon after Scott moved to Steubenville in 1826, he attended the annual meeting of the Mahoning Association, on August 20, as an invited guest and preached. The following year he was there again, somewhat reluctantly, because he was not a regular Baptist and did not want to impose upon the association's "hospitality." But Campbell urged him to come, and Campbell was a "messenger" to the association from the church at Wellsburg, which, though on the wrong side of the river and forty miles south of the nearest of the other churches, had its connection with the Mahoning rather than the Redstone Association.

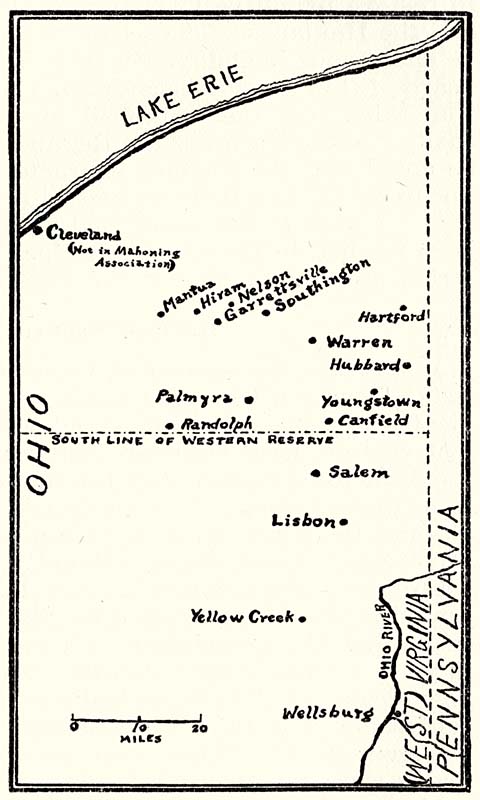

Churches of the Mahoning Association The Mahoning Association in 1827 listed seventeen churches. Fourteen of them were represented at this meeting. The reports for the year were not encouraging. There had been a total of thirty-four baptisms and thirteen additions otherwise... Thirteen had been excommunicated. The net gain was sixteen -- and this at a time when the population was SCOTT AND THE NEW EVANGELISM 187 doubling and redoubling. Wellsburg and Hiram, the two churches that had gone farthest in "reform," had done better than average; between them, they had twenty of the thirty-four baptisms and only one of the thirteen excommunications. The association decided that it needed an evangelist "to labor among the churches." It appointed a committee to find the man. The committee nominated Walter Scott, and the association elected him. He was to work for whatever the churches pleased to contribute for his support. Scott accepted the appointment. He was not a member of the association, not a Baptist, not a member of any church in the town where he lived, not a resident of the district in which the Mahoning churches were located, not an ordained minister. But it was a good appointment. SCOTT'S EVANGELISM IN THE MAHONING ASSOCIATION Scott began his work at New Lisbon, Ohio. The first convert under his new way of presenting the "ancient gospel" was William Amend, of whom Scott's early biographer, Baxter, says that he "was beyond all question, the first person in modern times who received the ordinance of baptism in perfect accordance with apostolic teaching and usage." This was on November 18, 1827. The statement does not exaggerate the conviction that Scott and his colleagues felt as to the importance of his recovery of the original process of conversion. Scott's formula for salvation rested upon the belief that religious knowledge and religious faith are within the reach of sinful man if he will apply his reason to the evidence supplied by revelation. His basic principle was that belief in the Messiahship of Jesus rests on rational proof, while everything else in the Christian system rests on his authority. That Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, is a truth that must be proved to man's reason. -- That done, "the strongest argument that can possibly be offered for the truth of the doctrine is this: Magister dixit."The formula itself was simple and clear-cut. There were three things for man to do, and they were all things that man could do and, having done them, could be sure that he had done them: he must believe, upon the evidence, that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God; he must repent of his personal sins with godly sorrow and resolve to sin no more; and he must be baptized. Then there were three things that God would do according to his promises, and man could be sure that God would 188 THE DISCIPLES OF CHRIST do them if the conditions had been fulfilled. God would: deliver man from the guilt, power, and penalty of his repented sins; bestow the gift of the Holy Spirit; and grant eternal life. Sometimes the second item of these last three was omitted in compact statements of the program, sometimes the third was omitted, sometimes these two were combined into one; so the whole usually appeared as a five-point formula. Taken by itself, the phrase, "gift of the Holy Spirit," had a rather vac, ie meaning. Taken together with "eternal life," it stood for growth in grace, Christian living, and the fulfillment of the Christian hope. Through this door Scott escaped from the seemingly legalistic rigidity of the earlier part of this formula, and the "scheme of redemption" (as Milligan later called it) opened out into a range of spiritual possibilities that were not limited by diagrammatic formulations. His preaching, at its best, had these overtones, this wider perspective. But he did not allow this to obscure the fundamental theme-"Faith, repentance and baptism for the remission of sins." Scott later called his formula "the Gospel Restored" -- a term which Campbell thought too pretentious. The force and. freshness of Scott's evangelistic appeal, the exciting sense of discovery, the thought that an ancient treasure of divine truth was just now being brought to light after having been lost for centuries, the sense of witnessing the dawn of a new epoch in the history of Christianity -- these things gave to the revival an extraordinary character. It was different from other revivals. It was -utterly unlike the Great Western Revival, which had stirred Kentucky and Tennessee a generation earlier and out of which had emerged the western branch of the "Christian" Church. Here was no frenzy of emotion, but a blending of rationality and authority, an appeal to common sense and to Scripture. It assumed the absolute authority of the Bible, which almost no one doubted; and it asserted man's rational ability to understand what he ought to do and why, and his moral ability to do it. The response was immediate and overwhelming. Other preachers in the association caught the new note and began to sound it. Hundreds were converted. New churches were organized. Within one year the total membership of the churches in the Mahoning Association was more than doubled. When the campaign had been in progress a few months, Thomas SCOTT AND THE NEW EVANGELISM 189 Campbell went over to see this wonderful thing. He saw clearly that Scott had added to the movement for reform a new element which had been lacking in his own work and in that of his brilliant son. He wrote: I perceive that theory and practice in religion, as well as in other things, are matters of distinct consideration.... We have long known the former (the theory), and have spoken and published many things correctly concerning the ancient gospel, its simplicity and perfect adaptation to the present state of mankind, for the benign and gracious purposes of his immediate relief and complete salvation; but I must confess that, in respect to the direct exhibition and application of it for that blessed purpose, I am at present for the first time upon the ground where the thing has appeared to be practically exhibited to the proper purpose. Thomas Campbell here says in substance: We have had the right plans for restoring the church as it ought to be and uniting it on the true and primitive basis, but we have had no effective way of getting anybody to join it; we have known everything about the gospel and its saving power except how to present it so that people would be saved by it. When the Mahoning Association held its next annual meeting, in August, 1828, the churches reported a net increase of 512 for the year. (The previous figure was 492.) The moderator, Stephen Wood, added that "these, however, are but the half of the actual number which have been by our means immersed into the Lord Jesus during the last year." Scott's report, as preserved in the minutes of the Mahoning Association for 1828, deserves to be presented here in full: Brethren, In conformity with your Minutes of 1827, 1 beg leave to report as follows: -- The results of your appointment have been important and peculiar. God has greatly blessed your good work. Many of the saints of the Mahoning churches have been strengthened during last year. Much error has been corrected; backsliders have been reclaimed, and many hundreds of all ranks have actually been converted and baptized into the name of Jesus Christ, our Lord. While these blessed results are connected with immense personal labors, by night and by day, in every minister concerned; yet we cannot, and would not avoid attributing them ultimately to the grace of God our Father, in turning our attention to the gospel in its original terms. 190 THE DISCIPLES OF CHRIST The publication of the gospel in the express form given it by the Apostles on Pentecost, and the public ministration of its spirit on their inspired plan, viz. in immersion, are facts which in the developement of reforming principles, are perhaps more intimately connected with the unity of the body of Christ, and the abolition of sects; the destruction of systematic divinity and the conversion of the world, than any other piece of solid knowledge which had been recovered to the church during the progress of three hundred years' reformation. To persuade men to act upon the divine testimony, rather than to wait upon uncertain and remote influences; to accept disciples on a simple confession of repentance toward God and faith in our Lord Jesus Christ, and to baptize them for in immediately personal acquittal from their sins through the blood of Christ, and for the Holy Spirit, are matters which have caused great public excitement. This excitement, however, his only turned out to the furtherance. of the gospel; and we bless God, who has taught us by his Apostles, that, as the divine testimony may be received when understood, and understood when honestly listened to: so it may be acted upon the very moment it is received. Therefore the enjoyment of remission and of the Holy Spirit, is not a thing of tomorrow, but of to-day -- "to-day," says God, "if you will hear my voice" -- "And there were added to them that very day three thousand souls." Beloved brethren, the bustle of conversion has precluded the possibility of holding more than two quarterly meetings, and all the monies which I have received have been expended in the payment of a horse, saddle, bridle, portmanteau, rent, and a balance of 25 dollars on a waggon; and even of the amount of these nearly 30 dollars have been borrowed, which I beg the Association may be careful at this time to refund. While I conceive the pecuniary part of this business not to have received that attention from. some, which was reasonably anticipated. T have nevertheless to acknowledge the kindness of many individuals, also, of some of the churches, particularly that of Wellsburgh, of Warren, of Canfield, Mantua, Salem, and New Lisbon, who will report more especially of what tliey have contributed. The families of Dr. Wright, brother Harsh, and brother Brookes, of Warren; brother Gaskill, of Salem; and brother Jacob Campbell, of New Lisbon, are of acknowledged hospitality, and have entertained not only me, but the whole church in their respective towns during these revivals; and with them those whose names follow, viz. -- The Rudolphs, the Deans, the Sacketts, the Drakes, the Hay's, the Haydens, the Austins, the Smyths, the Turners, &c. I may say of them what Paul said of such men formerly -- "They are the messengers of the churches, and the boast of christianity" SCOTT AND THE NEW EVANGELISM 191 The signal success which has attended the labors of brothers Bentley, Rigdon, and Gaston, is known to you all. Father Thomas Campbell has been about five months on the field, both increasing the number of disciples, and building them up in all the wisdom of the Just One. Brother Osborne abandoned all to come to the help of the Lord; but his first efforts disabled him. Ministers from several sects have embraced the ancient gospel, and preached it with great success. No fewer than six new churches have been formed, one of them with more than a hundred members; and the following brethren are now your preachers: -- Bosworth, who has already baptized many; Finch, Ferguson, Hayden, Wright, McLeery, Osborne, Jackson, Rudolph, Scott, Campbell., Rigdon and Bentley. The grace of God be with the brethren. Amen.

WALTER SCOTT

Joseph Gaston, mentioned by Scott in the last paragraph of his report as one of his valued colleagues, was a "Christian" preachers of whom Scott wrote, after Gaston's early death, that be was "the very first Christian minister who received the gospel after its restoration, and who argued for the remission of sins by baptism." It was clearly Scott's idea that the position of the Christians was so different from his own that it was a decisive step for a Christian minister to "receive the gospel." Gaston seems to have thought so, too, for (still quoting Scott) "he was immersed for remission at a general. meeting held at Austintown two years later." But even before that he had been a valued assistant in some of Scott's meetings, adding his "tender and pathetic exhortations" to the other's vigorous argument. Between them, they won to the new position many of the "Christians" in Ohio. Scott's biographer says: "Great numbers of them, sometimes nearly entire congregations, at once accepted his views, for which they were already prepared by an abandonment of creeds, the rejection of' all party names, and the adoption of the name Christian as expressive of their allegiance to Christ." (Baxter, op. cit., p. 150.) DISSOLUTION OF THE MAHONING ASSOCIATION At the annual meeting of the association in 1828, when the report of Scott's first year's work was received, William Hayden was added to the evangelistic staff, and the next year Bentley and Bosworth. Within three years after Scott's192 THE DISCIPLES OF CHRIST appointment, the Mahoning Baptist Association had been radically changed. There remained only one more thing that could be done to remove the last trace of its distinctively Baptist character; that was for the association itself to dissolve. It had come to be generally agreed that the churches should follow the New Testament pattern of government, and that there was no primitive precedent for anything quite like a Baptist association, which, while disclaiming de jure authority, nevertheless exercised a good deal of de facto control over the churches. Moreover, some other associations, notably Redstone and Beaver, were taking stern measures against churches and members that, influenced by Campbell's teaching in the two published debates and in the Christian Baptist, were shaking off their allegiance to the Philadelphia Confession of Faith and otherwise departing from Baptistic practice. It seemed to many that associations were unscriptural and might be dangerous. It was perhaps at Scott's instigation, certainly with his support, that John Henry introduced a resolution "that the Mahoning Association, as an advisory council, or an ecclesiastical tribunal, should cease to exist." Alexander Campbell, who was rising to oppose the motion was dissuaded by Scott. It was adopted unanimously. At that time and place, at Austintown, Ohio, in August, 1830, there came into being a company of Reformers who were not Baptists. "Those Baptists who had embraced the new views," says Baxter, "together with the new converts made, were called Campbellites, and by many Scottites; but after the dissolution of the Association which was really brought about by the efforts of Scott, they were called Disciples." But the actual beginning of the Disciples cannot be dated so precisely, because it consisted, not in the formation of some new organization, but in the separation of various groups of Reformers from their previous denominational connections and the merging of these into a people with some sense of common cause and mutual fellowship. Both the separations and the mergings were gradual processes. The dissolution of the Mahoning Association, with the substitution of an annual meeting of its constituent churches "for praise and worship, and to hear reports from laborers in the field," was only a single event among many, though perhaps the most decisive. SCOTT AND THE NEW EVANGELISM 193 THE PROCESS OF SEPARATION The separation from the Baptists had begun before 1830, and it was not completed until at least three years later. A few episodes in other places will illustrate the process. The thirteen churches which were excluded by the Redstone Association in 1825 because of their reforming views and which formed the Washington Association were thereafter Baptist in name only. Campbell's views gained wide currency in Kentucky after the Maccalla debate in 1823 and his extensive tour of the state in 1824. "Raccoon" John Smith, a somewhat eccentric but very powerful Baptist preacher, met Campbell in the latter year, read the Christian Baptist, soon learned Scott's method of presenting the gospel, and put it into practice. It was the evangelistic activity of the Reformers that so quickly gave them a preponderance in some associations and a large minority in others. The Baptist churches and associations in regions where the Reformers were active were virtually swamped with new converts, almost all of whom had come into the church on the new presentation of the "ancient gospel." Smith's three churches (Mount Sterling, Spencer's Creek, and Grassy Lick) in the North District Association of Kentucky, had 392 baptisms during the year 1827-28, and he had also evangelized in other communities. The twenty-four churches of the association reported 900 baptisms for that year, mostly by Smith "after the ancient practice. "Besides, he had organized five new churches "on the Bible alone" which had joined the association. No wonder the orthodox Baptists who had filed charges against him the year before did not now care to bring them to a vote. It was for this same year that the Christian Baptist (Vol. V, p. 263) reported: "Bishop (i.e., Elder) Vardeman, of Kentucky, has immersed about 550 persons from Nov. 1 to May 1. Bishop John Smith from Feb. 1 to April 20 immersed 330. Bishops Scott, Rigdon and Bentley in Ohio within the last six months have immersed about 800." To get away from the flood of John Smith's "Campbellite" converts, ten churches of the North District Association withdrew and formed a new purely Baptist association. The remaining majority, now composed wholly of Reformers, met once more and then dissolved, as the Mahoning Association had done.Tate's Creek Association, in Kentucky, followed the example of Redstone, in that an orthodox minority excommunicated a 194 THE DISCIPLES OF CHRIST reforming majority, when ten churches that remained soundly Baptist excluded sixteen that followed Campbell. The Beaver Association, in western Pennsylvania, adopted a resolution in 1829 disfellowshipping Mahoning and giving a syllabus of the errors charged against the Reformers who dominated it. This statement, which was more accurate than one side usually gives of the other's views when controversy is hot, is sometimes called the "Beaver anathema." According to it, the Reformers teach (and the Baptists, by implication, deny): "that there is no promise of salvation without baptism; that baptism should be administered on belief that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, without examination on any other point; that there is no direct operation of the Holy Spirit on the mind before baptism; that baptism procures the remission of sins and the gift of the Holy Spirit; that man's obedience places it in God's power to elect to salvation; that no creed is necessary for the church; that all baptized persons have a right to administer the ordinance of baptism." To these items, Tate's Creek Association added four more "Campbellite errors": "that there is no special call to the ministry; that the law given to Moses is abolished; that experimental religion is enthusiasm; that there is no mystery in the Scriptures." Since there was no criticism of the Reformers for practicing open communion, they evidently did not practice it at that time. Some other Baptist associations in Kentucky condemned Campbell's doctrines without taking specific action to exclude those who held them. An association in Anderson County (just west of Lexington) adopted the Beaver anathema, after which several churches voluntarily withdrew, and the record shows a sudden drop in the membership both of the association as whole and of every church remaining in it except one very small one. Sulphur Fork Association, in 1829, recorded its approval of the Beaver action and advised its churches to "discountenance the several errors and corruptions for which Mahoning has suffered excision from the fellowship of the neighboring associations." Goshen Association, a hundred miles west of the Bluegrass, resolved, in October, 1830, "that the doctrines of A. Campbell are anti-Christian, and that the churches and members of this association are requested not to countenance or give encouragement to any person or persons holding the opinions of the said A. Campbell by inviting SCOTT AND THE NEW EVANGELISM 195 them into their pulpits or private houses for the purpose of disseminating their anti-Christian doctrines or opinions." In 1830 Long Run Association, including Louisville, passed firm but courteous resolutions condemning Campbell's position; but it was already permeated with reforming sentiment, and the Louisville Baptist church had peaceably divided, even sharing the property on fair and friendly terms. P. S. Fall, as pastor of that church, had started it on the way to reform before he removed to Nashville in 1825. The work was carried on by his successor, Benjamin Allen, of whom J. H. Spencer's History of the Kentucky Baptists says: "He brought many into the Baptist church, but he took many more out of it. The Campbellites owe him more, and the Baptists less, than any other man in Long Run Association." Allen was to Long Run Association what John Smith was to North District, Jacob Creath to Elkhorn, and Walter Scott to Mahoning. By the end of 1830 there were in Kentucky several thousand persons committed to the program of reform. This following had been won, partly by the direct influence of Campbell's visits and writings, but largely by the evangelistic work of men like John Smith, Jacob Creath, Sr., and Jacob Creath, Jr., from the previously unconverted, as well as from the Baptist churches. These were ready to recognize their common fellowship in a new and separate body when Mr. Campbell himself ceased to classify himself as a Baptist. This he did when the Mahoning Association dissolved and when be brought his Christian Baptist to an end and began the publication of his new magazine, the Millennial Harbinger. These thousands who entered the reformation through what had been Baptist churches were in addition to the other thousands of members of the "Christian" churches who cherished many of the same ideas of reform. In Virginia, the action of the orthodox Baptists against the Reformers was led by Robert Semple and Andrew Broaddus, men of a high type whose personal relations with Mr. Camp bell were those of mutual esteem. This, however, did not prevent decisive action. The Appomattox Association in 1830 adopted the Beaver syllabus and added three resolutions: to discountenance the writings of Alexander Campbell; to discourage the use of his new translation of the new Testament; and not to invite into its pulpits any minister who holds 196 THE DISCIPLES OF CHRIST Campbell's views. The Dover Association, which included Richmond, condemned a long list of errors (the "Dover anathema") in December, 1830, and two years later withdrew fellowship from six ministers who called themselves Reformers. Alexander Campbell had preached in Richmond and gained a following while he was in that city as a member of the Virginia Constitutional Convention in 1829. Thomas Campbell went there in 1832 and helped in organizing what became Sycamore Church, "the first full-fledged Church of Christ in Virginia" (Thos. Clemmitt, Jr.: Old Sycamore Church, 1932). From Tennessee came this lament from a Mr. McConnico who wrote (1830): "O Lord, hear the cries and see the tears of the Baptists, for Alexander hath done them much harm. The Lord reward him according to his works!" The process of separation was well advanced by the end of 1830, but it was not complete. Individuals with Disciple sympathies lingered in some Baptist churches, but they were being put out as fast as they were discovered. In 1833 one E. A. Mills was expelled from the Baptist church at Eagleville, Ohio, because, as the clerk's record says, he "will not consent to abandon the reading of Mr. Campbell's 'Millennial Harbinger.'" Eighteen other members who remonstrated were also excommunicated. (A. S. Hayden: Early History of the Disciples in the Western Reserve, pp. 352f.) By 1833 the separation was virtually complete. During these stormy years there were three events which extended the reputation and enhanced the prestige of Alexander Campbell, and thus indirectly affected the history of the Disciples. These were: his publication of a new translation of the New Testament; his debate with Robert Owen; and his service in the Virginia Constitutional Convention. CAMPBELL'S NEW TESTAMENT Mr. Campbell had unbounded reverence for the Bible but no special reverence for the King James Version. He was too familiar with the first century Greek of the New Testament to feel that the English of 1611 was sacrosanct. He may have appreciated the excellence of its literary style -- though he does not speak too respectfully of it -- but the important thing was the meaning of the sacred text, and he was sure that this could be rendered more accurately than it was rendered in the "authorized" version. Borrowing a translation that hadSCOTT AND THE NEW EVANGELISM 197 been made half a century earlier by three Scottish divines -- George Campbell, James MacKnight, and Philip Doddridge -- and published in Great Britain, he made "various emendations," added a preface and 100 pages of critical notes and appendices, and published the whole from his own printing office in 1828. In the preface he defends the making of new translations with much the same arguments that are used more than a century later by the makers and promoters of new versions of the Bible. The chief reasons are that modern scholarship has produced a better text and more thorough knowledge of the ancient languages than the seventeenth century possessed, and that "a living language is continually changing." Further, he was resolved that every word of the Greek should be translated into clear English, and that none should be merely transliterated. There had never yet been a complete English translation. Baptizein was, of course, the word he had in mind. So he wrote "immerse" wherever the older versions had "baptize." John the Baptist is "John the Immerser." This naturally gave great offense to all non-immersionists and, strangely enough, to most of the Baptists, too. The substitution of modern diction for the Jacobean, which is still so commonly mistaken for distinctively biblical language -- "you know" for "thou knowest... "goes" for "goeth" -- seemed sacrilege to many. Nevertheless, the new translation had a circulation. Its third edition, revised and enlarged, was published in 1832 at "Bethany, Brooke County, Va.," the name which had taken the place of "Buffaloe" to designate the post office of which Mr. Campbell was the postmaster as well as the principal patron. Other editions followed. THE CAMPBELL-OWEN DEBATE The debate with Robert Owen gave Alexander Campbell an opportunity to exercise his talents in a wide field and perhaps brought him the greatest publicity he bad as yet received. It was held in Cincinnati, April 13-23, 1829. Mr. Owen, known throughout Europe and America as a philanthropist and humanitarian, a radical social reformer, and a militant atheist, had bought the property of the Rappite colony at New Harmony, Indiana, five years before and was engaged in constructing there a Utopia on communistic lines and without religion. The social experiment was interesting, and198 THE DISCIPLES OF CHRIST ultimately disastrous; but the debate touched it only incidentally. Early in 1828 Mr. Owen, then in New Orleans, had issued a general challenge for any reputable minister to meet him in public debate. Campbell responded. Soon afterward Mr. Owen visited Mr. Campbell at Bethany, and they arranged the time and terms of the debate. Both were busily occupied during the year that was to elapse before they met on the platform -- Campbell with the Christian Baptist, the affairs of the churches which were in the act of separating from the Baptists, and his second marriage; Owen with a trip to Europe, which was followed by an expedition to Mexico, where he became so busy getting a grant of land and planning a new social experiment that he almost forgot about the debate, the Mexican government having to send him across the Gulf in a gunboat so that he could keep his engagement in Cincinnati. Mr. Owen undertook to prove that all religions are founded upon ignorance and fear; that they are in conflict with certain unchanging natural laws, twelve laws which he had worked out with great exactness; that they are the source of vice, strife, and misery for man and are a hindrance to the formation of a society embodying virtue, intelligence, and good will; and that they are maintained only by the tyranny of the unscrupulous few over the ignorant many. It thus became Mr. Campbell's role to stand forth as the champion not only of Christianity but of the basic concepts of a religious view of the world as well. He had already dealt extensively with this topic in his "Six Letters to a Skeptic," in early issues of the Christian Baptist. There, his main argument was that the Bible must be a revelation from God because, according to the accepted principles of Locke's philosophy of sensation and reflection, man cannot even form an idea of God by his own powers. In his famous "twelve-hour speech" against Owen, he dealt with the historical evidence for Christianity, the evidence from prophecy, and the genius and tendency of Christianity, ending with a critical examination of Owen's godless social system. The systems of thought which the two men defended were direct opposites, but their minds never met, much less clashed, on the issues involved because they moved on different tracks. Owen paid no attention either to Campbell's positive arguments or to his rebuttals but devoted SCOTT AND THE NEW EVANGELISM 199 himself persistently to the exposition of his "twelve laws of nature." Campbell, recognizing the futility of arguing from history or philosophy with an opponent who would not listen, addressed the audience with the affirmations that Christianity "changes, regenerates and reforms wicked men;" that, whereas materialists admit that their system cannot make bad men good, Christianity can and does, not by law but by love; and that "the character of Jesus Christ weighs more in the eyes of cultivated reason than all the miracles he ever wrought." Much later, after the last of his debates, Mr. Campbell said that, of all his opponents in debate, "the infidel Robert Owen was the most candid, fair and gentlemanly. "The English author Mrs. Trollope, then living in Cincinnati, described the debate at some length in her Domestic Manners of the Americans. She was impressed by Mr. Owen's suavity, by Mr. Campbell's forensic ability and power over his hearers -- "the universal admiration of his audience" -- and by the fact that the two debaters never seemed to lose their tempers but usually went off to dinner together like cronies when they had finished denouncing each other's doctrines on the platform. Mr. Campbell's brilliant defense against the common foe of all religions enhanced his reputation and brought both publicity and prestige to the movement which, under his leadership, was just emerging into a visible existence. VIRGINIA CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION When Mr. Campbell announced his candidacy for election as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1829, which was to rewrite the constitution of Virginia, he was criticized for turning from heavenly things to follow the path of worldly ambition in politics. His defense was that be wanted to do something toward ending slavery in Virginia. He was elected, served in the convention, and took a prominent part in debate. Yet he never raised his voice about slavery. Any who would take this as proof that the reason was not sincere will find, by studying the history of that convention, that this apparent contradiction is easily explained, and to Mr. Campbell's credit. He found that the constitution of Virginia placed all political power in the bands of the slave-owning aristocracy. Representation in the legislature was heavily weighted in favor of the eastern counties, where the great plantations were, as200 THE DISCIPLES OF CHRIST against the western part of the state, where there were few slaves and where there was much sentiment in favor of emancipation. The political leaders were determined to freeze that arrangement in the new constitution, together with the property qualification for voting, which served as a further bulwark for slavery. There was no use in trying to write into the new constitution a clause empowering the legislature to do anything about slavery if the legislature itself was left in the hands of the slave-owning class. Mr. Campbell led the fight to democratize the government of Virginia. Against him he had the greatest array of political talent and reputation that had been assembled since the Federal Constitutional Convention of 1787. James Madison and James Monroe, both former presidents of the United States, were there. John Marshall, chief justice of the United States, took time off from that high office to sit in the Virginia convention. John Randolph of Roanoke was president of the convention. All were on the side of the oligarchy. Mr. Campbell crossed swords with them all. Reading those speeches today in the printed minutes of the convention and ignoring, if one can, the names and reputations of the speakers, one would say that, for argument and eloquence and for understanding of the principles of a democratic society, the victory lay clearly with the young preacher from the far northwestern corner of the state. But the others had the votes. While he was in Richmond in attendance at the convention, Mr. Campbell did not fail to let his light shine in the religious field. He preached every Sunday in one of the churches of the city. Many of his fellow delegates went to hear him. Former President Madison is quoted as saying that he had heard him very often as a preacher and regarded him as "the ablest and most original expounder of the Scriptures" he had ever heard. Others also were impressed, and the seeds of future churches in Richmond were sown.

[201]