Mormon Classics | Spalding Library | Bookshelf | Newspapers | History Vault

|

Frederick A. Henry

(1867-1949) Captain Henry of Geauga (Cleveland: The Gates Press, 1942) |

|

White's thesis (1931) | McKiernan's Rigdon bio. (1971) | Van Wagoner's Rigdon bio. (1994)

Wm. H. Whitsitt's Rigdon bio. (1891) | C. M. Brewster's MS (145) | Criddle's essay (2005)

Pioneer & General History of Geauga Co. (1880) | Memorial to the Pioneer Women (1896)

Excerpt provided below, copyright 1942 by Frederick A. Henry

|

C A P T A I N H E N RY O F G E A U G A A Family Chronicle BY FREDERICK A. HENRY CLEVELAND: THE GATES PRESS MCMXLII |

|

Contents

Illustrations

|

|

[ 1 ]

The Scotch-Irish country in the province of Ulster, whence sprang the Henry line that is herein dealt with, is substantially the Northern Ireland of today. The region so peopled comprised, with some overflow, the coastal counties of Londonderry, Antrim, and Down, and southwest of them the inland counties of Tyrone, Armagh, and Fermanagh. Of these, Tyrone and Londonderry occupy the area encircled by the broadly curving valleys of the Foyle and the Bann, which flow northerly by the ports of Derry and Coleraine, thirty miles apart, through lake or estuary into the sea. In 1610, under James I, most of this territory became crown land, by confiscation from the rebellious Irish nobility -- an exercise of arbitrary power which, whether wise or unwise, has kept the Irish question white-hot in British politics for over three centuries. The famous Plantation of Ulster ensued, under royal favor, and soon repeopled the region, chiefly with thrifty and intelligent Scottish Presbyterian colonists, whose descendants became the celebrated Scotch-Irish -- a race tall, angular, and sinewy in body; in habit pious, opinionated, and untidy; but, on the whole, fitted both physically and mentally to excel. A century later, in 1718-1720, a prolonged drouth, a series of epidemics, and a depressed state of the linen export trade, together with the long endured and ever increasing oppression of extortionate rents and compulsory religious conformity, induced wholesale migrations of Ulstermen to America. 1 Though most of the Scotch-Irish landed in Boston, and settled mainly in the frontier towns of Massachusetts and New Hampshire, many were scattered through the colonies from Maine to South Carolina. Viewed by both Puritan and Cavalier with British prejudice against the "Irishmen," they nevertheless became in half a century a most important element of the population in both numbers and influence. 2 __________ 1 The romance of this movement is nowhere more vividly or truthfully portrayed than in the Reverend Elijah Kellogg's Good Old Times. It is pleasant to recall that my boyhood copy of this stirring tale, when in 1880 I lent it to "Grandma" Garfield in Mentor, gave her such delight, with its pictures of pioneer struggles very like her own, that for some time afterwards, in token of her grateful regard for the lender, she treasured in her Bible some of his youthful letters to her grandsons. 2 Says the Reverend Doctor Maclntosh in his "The Making of the Ulsterman" (The Berea Quarterly, October, 1908, at page 9): "The plantation of the Scot into Ulster kept for the world the essential and best features of the lowlander. But the vast change gave birth to and trained a somewhat new and distinct man, soon to be needed for a great task which only the Ulsterman could do; and that work -- 2 CAPTAIN HENRY OF GEAUGA The patronymic Henry appears in the early eighteenth century town or county records of every colony where the Scotch-Irish settled. The petition of March 26, 1718, signed by over two hundred "Inhabitants of the North of Ireland," to Governor Shute of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, for "suitable encouragement" of "their inclinations to transport" themselves and their families to New England, bears the signatures of Robert and James Henry, Robert Hendre, and William and Robert Hendry. From eight different towns, moreover, in Tyrone, Londonderry, Antrim, and Down, nine commissioners and ruling elders of the name Henry, though none apparently of the name Hendry, figure in the records of presbytery and synod in Ulster between 1691 and 1718. In the next twenty years there appear on this side of the ocean, in the Massachusetts Bay Colony alone, at least nine distinct, though not necessarily unrelated, Henry families, besides one or more of the name Hendry. Like-sounding when uttered with the Celtic burr, the two names are perhaps identical in origin, as indeed, by the common dropping of the "d" in Hendry, they are often indistinguishable today. Descended from one of these Scotch-Irish Henrys in Massachusetts (for I set aside as incredible, the tradition current in one of the remote female branches of this family, 1 that their progenitor was "the Regicide Whalley, who went by the name of William Henry to evade recognition by the officers of Charles II"), CHARLES EUGENE HENRY, the subject of this narrative, was of the sixth generation of his family in America; the line being: William, Robert, John, Simon, John, Charles. The earliest record bears date an even century before his birth. It discloses that on June 24th, 1735, William Henry, husbandman, of Stow, Massachusetts, purchased from Nathaniel Page, of Lunenburg, one hundred and sixteen acres of land, besides eight acres of meadow, in the northeastern part of the latter town. A few years later, his eldest son Robert Henry, also of Stow, removed with his wife Eleanor and their first-born child John to that part of the neighboring town of Groton which was later set off as Shirley. Sometime after Robert's death in 1759, John, who became by occupation a mason and builder of chimneys, removed to Columbia, then a part of Lebanon, Connecticut, and known as Lebanon Crank. There he married Mary, youngest daughter of the Reverend William Gager (Yale College, 1721) and of Mary Allen, his third wife. There, too, their first child, Simon Henry, was born on November 27, 1766. _________ 1 Genealogy of the Fuller Families Descending from Robert Fuller, by Newton Fuller, of New London, Connecticut, 1898; page 11. _________ which none save God, the Guide, foresaw -- was with Puritan to work the revolution which gave humanity this republic." Voluminous lists of persons, places, ships, etc., concerned in the movement of Ulstermen to America, appear in Charles K. Bolton's Scotch, Irish Pioneers in Ulster and America (Boston: Bacon and Brown; 1910), and in Stimner G. Wood's Ulster Scots and Blandford Scouts (published by the author, West Medway, Massachusetts: 1928). SIMON HENRY AND RHODA PARSONS 3 At that time Lebanon was distinguished as the site of the Reverend Eleazer Wheelock's Indian Charity School, which Joseph Brant, the Mohawk warrior, then a youth, had recently entered as a pupil, and which, by evolution and transfer to New Hampshire, finally became Dartmouth College. Lebanon gained further renown, a few years later, from the efficient War Office there maintained under the patriotic eye of Connecticut's bluff old Revolutionary governor, Jonathan Trumbull. From this town John Henry had a brief record of service in the Revolution. He then removed successively to Bolton, Andover, and finally to Enfield, Connecticut, where he filled divers minor town offices, and died in 1819, aged seventy-six years. His widowed mother Eleanor had died there in 1807; his wife in 1812. Simon Henry married in the same town, in 1792, Rhoda Parsons, who, born March 13, 1774, was fourth of the nine children of John and Ann (Osborn) Parsons and came of most respectable ancestry. 1 His mother and wife thus brought into the Henry line of descent two successive strains of fine old Puritan stock, which was henceforth to preponderate over his father's vigorous Scotch-Irish blood. The young couple removed shortly to Middlefield, Massachusetts, and thence to Washington, Berkshire County, where for a quarter-century they cultivated their farm and reared a family of ten children. Here Simon Henry was repeatedly chosen moderator of the town meetings and first of the three selectmen elected annually, besides discharging many other public functions down to the very date of his removal to Ohio. In 1812-1813, a war-time period of especial responsibility, he was sent to the legislature, or General Court, and soon afterwards his three oldest sons served their country in the second war with Great Britain. Notwithstanding this prosperity amidst the lovely but sterile Berkshire Hills, New Connecticut (as the Western Reserve in Ohio was then often _________ 1 She could number among her forefathers Deacon Benjamin Parsons, and Richard Vore, as well as John Keep and John Leonard, both of whom were among the six persons killed at Pecowsick Brook on March 26, 1676, when, as they and others were proceeding peacefully with their families, under a strong but craven armed escort, to church in Springfield, Massachusetts, Caused Captain Nixon and forty men to run. In her veins, moreover, coursed the mingled blood of Robert Pease, William Warriner, Richard Montague, Thomas Marshfield, and of Deacon Samuel Chapin, in whose widely copied statue, as "The Puritan," by St. Gaudens, the city of Springfield publicly and worthily commemorates New England's pioneers. She descended, too, from Robert Goodell, John Adams (not the president), William Vassall, John Osborn, Richard Oldage, Begat Eggleston, John Talcott, John Stiles, and other worthies among the first settlers of New England. 2 Among other committees to which he was assigned was one to "perambulate Peru": i. e. to join a representative of that town in walking along the boundarv line between it and Washington and in repairing or restoring the monuments or freshening the blazes on the trees which marked its course. Another was to "reseat the meeting-house," meaning thereby not the changing of the pews, but the assigning of the church sittings among the members and parishioners according to the respect due and the tribute received in each case. 4 CAPTAIN HENRY OF GEAUGA called) appealed to their imagination as a land of greater promise. In an obituary notice which Father wrote of one of the earliest pioneers of this region, Rachel McConotighey, the widow of his uncle William Henry, for the Chagrin Falls Exponent of September 13, 1888, he said: During the years... 1815, 1816, and 1817, settlers came in great numbers from the East, and the somber forest that covered a score of counties south of Lake Erie was dotted here and there with clearings. The burning brush and log heaps became a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night. In every township one or two churches and half a score of schoolhouses sprang up as if by magic, and social life, together with township and county government, became more marked. Nearly a quarter of the people of the town of Washington emigrated west-ward in the decade 1811-1820, and Simon Henry, anxious to provide for the settlement of his sons, procured from Simon Perkins, of Warren, in exchange for the Massachusetts farm, a much larger tract in Bainbridge, Geauga County, Ohio. To Ohio, therefore, with his wife and eight children (two of the older ones, Orrin and John, having been sent ahead the year before) he removed in the autumn of 1817, a year described in Villard's John Brown (at page nine) as one not only of extreme scarcity of money "but of the greatest distress for want of provisions known during the Nineteenth Century." His terse diary of their forty-five days' journey 1 into the heart of the wilderness begins: "We started from home Sept. 18th on Thursday in the afternoon and staid at Wm. Noble's." The next night, at New Lebanon, they put up at Pierce's tavern, where the charge "$1.57" seems well worth recording. With a daily progress of about fifteen miles, their only long stops en route were a three days' visit at Smyrna with Rhoda's brothers John and Elam Parsons, and four days at Madison, near their journey's end, to await word from their sons at the new location before proceeding farther on the main road west or venturing from it into any doubtful byway. Finally on November 1 the last entry reads, "Saturday night home." From the Berkshire Hills to the Western Reserve they had come nearly six hundred miles, but their pilgrimage began and ended at "home." The advent of the Henrys is thus recounted in the Pioneer and General History of Geauga County (page 137): In Washington they were neighbors of George and Robert Smith and John Fowler, who had preceded them to Ohio by a year or two. George Smith's family were their nearest neighbors, and when they parted with them it was without hope of meeting them again. Two years after the departure of the Smiths, they decided to try their fortunes in the wilds of Ohio, so, bidding good-by to their friends, they started on the wearisome forty days' journey. _________ 1 They traveled via New Lebanon, Albany, Union, Sharon, Middlefield, Cooperstown, Sherburne, Smyrna, Nelson, Tully, Skaneateles, Geneva, Canandaigua, Bloomfield, Avon, Batavia, Btiffalo, Fredonia, Northeast, Erie, Conneaut, Saybrook, Madison, Painesville, Mentor, Chester. PIONEERS IN BAINBRIDGE 5 The last night of the journey they stayed at Hudson's Corners in Chester. Between there and the center of Bainbridge there was but one house, and that without a tenant (built and afterwards occupied by Gideon Russell of Russell township). Orrin, the oldest son, met them in Chester with two fresh teams, and the Smiths and Fowlers came up soon after and kept them company through the day.... With George Smith and Simon Henry, especially, was this a glad meeting. They [had] worked together while young men, clearing their rugged mountain farms, and when, after a separation that both thought final, George Smith rode up to them, those men of fifty years could only clasp hands while the starting tears expressed what their tongues refused to tell. With the help of fresh cattle, their own jaded ones were enabled to be at nightfall within a half mile of their future home. This now smooth meadow was then a black ash swamp, and after struggling over roots and through mud till about halfway across, the wagon settled hopelessly down in the mire, and in spite of all the drivers could do, had to be abandoned for the night. The mother and smaller children were carried to dry land by the grown-up sons; the girls and Calvin (a boy of nine) had been sent off before dark on the horses of their old neighbors, and were already among friends. Packing on their backs the necessary articles for cooking, they went on foot to the cabin which the sons had built, whose ample chimney gave them a view of the tree-tops waving in the November wind. They were the ninth family in the township, and with the three young men and as many young women, made an important accession to the isolated settlement. The first settlement of Bainbridge township dates from 1811, with the coming of David McConoughey, of Blandford, Massachusetts. He was followed quickly by Jasper Lacy and Gamaliel H. Kent, of Suffield, Connecticut. In 1812 came Alexander Osborn, of Blandford, and two years later George and Robert Smith, of Washington. Enos D. Kingsley emigrated from the adjacent town of Becket, Massachusetts, in 1816, and was joined the next year by his neighbors, Joseph Ely, of Middlefield, and John Fowler and Simon Henry, of Washington. These were followed in 1818 by Deacon Jonas H. Childs, of Becket, Justus Bissell, of Middlefield, and by Daniel McFarland and Philip Haskins, of Adams, Massachusetts. Surrounded thus by old neighbors, the Henrys for many years dwelt peacefully in their new home, till Simon Henry, often chosen a justice of the peace or a township trustee, died on June 26, 1854, in his eighty-eighth year, having survived his wife by seven years. His grandchildren remembered him as a stoop-shouldered, blue-eyed old man, with horny hands forever gathering highway pebbles into capacious coat pockets and lodging the same in some rut farther along his farm front; or, dim of sight, rising from his chair by the doorstep to accost some passer-by with a commanding, "Well, who are you?" while, with foot or hand on the wheel of the traveler's vehicle, he detained him willy-nilly till the inquirer's curiosity was appeased. His wife Rhoda, black-eyed, keen-minded, and kind-hearted, added her contribution to the strain of vigorous, assertive personality which they handed on. 6 CAPTAIN HENRY OF GEAUGA Their son John Henry, father of the subject of this book, was born in 1796, and had just attained to man's estate on the family's arrival at their new home in Ohio. The lad, it is said, had been selected by Mr. John Parsons, of Enfield, Connecticut, from among his daughter Rhoda's large family, to go back home with him from Berkshire and attend school in the older community; thus lightening the mother's growing burden, while enlarging the opportunity of one by no means the least promising of her children. Afterwards, when his father in 1813 was sitting in the General Court, John, then at Latin School near Boston, witnessed with him the great reception tendered to Commodore Bainbridge, on the latter's arrival there in February, with his flagship Constitution, after capturing the British frigate, Java. Inspired no doubt by this spectacle of martial glory, and chafing withal beneath fraternal gibes The family had hardly settled in the new country, when the young scholar John Henry was finding welcome relief from the endless toilsome grappling with the forest by "keeping" school in winter. While thus engaged in the older settlement of Canfield, Ohio, some forty miles to the southeast, whither he had been called to teach in a select school for advanced pupils, including some with experience as teachers, he met and on the first of July, 1819, he married one of his teacher-pupils, Polly, the seventh child of Captain Simon and Ruth (Hanchet) Jaqua. Born in Salisbury, Litchfield County, Connecticut, on May 1, 1800, Polly Jaqua had come with her parents to Johnston, Trumbull County, Ohio, in September, 1804. Her father, said to have been a minute man in the Revolution (though I have never found any record of his service), was the first justice of the peace in that township; and his father, Aaron Jaqua, whose wife was Rebecca House, of Lebanon, had been a Connecticut soldier and "clerk" in the French Wars. The absurd tradition, often repeated by their romantic granddaughter Polly, that her "honored father was descended on JAQUA LINEAGE 7 the one side from Lord House, and on the other from Cardinal Jaques," if not always implicitly credited, stood at least unchallenged, until one of her grandnephews, who had taken orders in the Episcopal Church, became curious about his jaqua ancestry. Thereupon the scandalous cardinal's pretensions were speedily and indignantly shattered on the rock of sacerdotal celibacy. It is perhaps needless to add that neither branch of this family legend derives any support from the actual records of Simon Jaqua's honorable New England lineage. 1 To some, indeed, Polly's vitality and Gallic impulsiveness lent color to the notion (derived originally, it may be, from the peculiar surname) that she came somehow of French descent, if not from the dubious prelate, then certainly from Huguenot stock. Old Doctor David Shipherd, for example, benignant and oracular, once flattered her prankish boy Edward by descanting upon his "Huguenot birthright of industry, longevity, the moles on your back" (he had seen the boys of both households "in swimming" together in the Chagrin), "your music, persistence of accomplishment, and liberality." But though the Jaquas came to Connecticut from North Kingston, Rhode Island, where indeed the Tourgees, Ayraults, and other French Huguenots found asylum after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes on October 18, 1685, the family settlement there antedates by some years that crisis in the world's history. At least four of the name Jaques (for so it was originally spelled) fought in King Philip's War, wherein the famous capture of the Narragansetts' fort in the Great Swamp Fight of December 19, 1675, occurred at South Kingston, only a few miles south of the seventeen hundred and forty acres granted on January 1, 1672, to a quartet of coadventurers, including Polly's ancestor, Thomas Jaques, one of the four. 2 Of Polly Jaqua's grandfather, a curious relic still extant is a small leather-bound book of Gospel Sonnets or Spiritual Songs (Glasgow, 1760), much worn, and inscribed in a clerkly hand, "Aaron Jaqua's Book, a Present from his son William Tupper, in the Army of the United States, Jany 5th, 1782." First of these gospel sonnets is an old song entitled "Smoking Spiritualized," to which a second part is newly added. Each part has five pious stanzas, and each stanza ends with the admonitory refrain, "Thus think, and smoke tobacco." In The Oxford Book of English Verse, selection Number 390 (a poor variant of Part I) omits the most interesting stanza, _________ 1 The Jaqua (or Jaques) line, beginning with the immigrant to America, runs: Henry, John, Abraham, Thomas, Ebenezer, Aaron, Simon, Polly. That of Aaron Jaqua's wife: Samuel (son of the Reverend John House, of Eastwill, County Kent, England), Samuel, Jr., Nathaniel, Rebecca. That of Simon Jaqua's wife: Deacon Thomas Hanchett, Deacon John, John, Ebenezer, Amos (Hanchet), Ruth. 2 Aaron Jaques, uncle of the Aaron Jaqua who married Rebecca House, served in that war tinder Captain Jonathan Remington, of Cambridge, Massachusetts, -- a circumstance corroborative of other evidence that the Rhode Island family descended from Henry Jaques, who emigrated from Wiltshire, England, to Newbury, Massachusetts, in 1640. In Shakespeare's "As You Like It," a Jaques, it will be remembered, attended upon the exiled duke in the Forest of Arden. 8 CAPTAIN HENRY OF GEAUGA which alludes to the old time smocker's habit of burning out his clay pipe in the fire to make it draw: Think on thy soul defil'd with sin; For then the fire It does require. Thus think, and smoke tobacco. Even more strongly in another particular did Aaron jaqua influence the lives of his descendants. After the early death, in 1782, of his daughter-in-law, Charity Grinnell, he counseled his widowed son, Simon, to choose for a second wife, Ruth Hanchet, "because," as he prudently observed, "the Hanchets live forever." This young woman, the daughter of Amos and Hannah (Holly) Hanchet, of Salisbury, Connecticut, and seventh in the line of Deacon Thomas, of Wethersfield, did indeed so happily unite in her own person the qualities of piety and longevity, as amply to justify her father-in-law's observation, construed either carnally or spiritually. In the flesh Ruth Jaqua lived to be ninety-one, and her daughter Polly to be nearly eighty-one; while each, during a long widowhood and almost until death, tended her own dairy throughout the week, and on Sunday journeyed horseback some miles to church. As throwing light on the personalities of these sterling pioneer women, whose scant advantages meant for them no lack of faculty of the non-academic sort, I quote verbatim the following letter, from mother to daughter, written from Crawford County, Pennsylvania, in the former's seventieth year, after she had visited the younger woman's rapidly growing family in Geauga County, Ohio, by horseback journey past their old Trumbull County home, sixty miles each way on the forest-girt roads:

Followfield March 10 1832.

Throw the goodness of an all wise Being I am in the land of the liveing yet And enjoy my health very well Praised be The Lord for his goodness to me -- I yest Receivd your leter dated febury 5 was very Glad to here from you it being the first I have Heard from you sence i came from your house You speake of troubles trust in the Lord he will Suport you yes in six and in seven he will Not forsake you take courage then his Grace is Suficient for you -- O my Child I feel for you and Yours -- But to tel you of my journey home MOTHER AND GRANDMOTHER 9 Had to stay there 2 weeks A great meting Cauld 4 days meeting began thursday Continued Til monday morning Prayer meeting every night & every morning before sun rise -- Wensday evenig Before that meeting Mr Weeb caried me Up to here Elder Eddy preach and Carroline Bates was maried to A Dicson Next day the prispoterioti Meeting Began Mr. Johnson's Tow sons one Daughter was Converted to God Welthy hine Hirum hine Lucy ann Dickson Harret Hill and more to the amount of 40 Charyty came here the first day of February made me A short viset it was very pleaseing to me I should be very glad to have a viset from you Mr Joseph Leech has lost there oldest Boy he Died happy in the lord, there little girl exsperienced Religion & tinited with the Church Brother Hitchcock is to preach here today And I must Conclude Wishing you health and prostperity My Respects to your family and all enquierin friends

Ruth Jaqua

The following, written by her daughter seven years later, while both were visiting in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, is probably a mere memorandum rather than a letter:

Orange, May 7th 1839 --

Mother will be seventy seven next November she has rode horseback 60 miles to see myself and family -- arrived last tuesday -- wednesday T was 39 years old-thirsday we all attended the funeral of Amasa Russ -- died of inflamation in head -- yesterday Monday we started to visit a son of uncle John H[anchet] M. B. who died April 24th 1837 aged 73 -- found them well pleasant family -- call'd at good B. Fords -- had short and good visit b F prayed powerful 1 -- had a melting time -- with flowing tears. I remembered the happy times when we had met in days of other years -- feel if I could enjoy such privileges I could sincerely say fearless of Hell and gastly death I break through every foe -- The wings of love and arms of faith would bear me conquer through. My dear Father Simon Jaqua was born June llth, 1754 and died June 25th 1825 -- aged 71.

Polly Henry

Before his death, the early date of which is thus carefully minuted, Simon Jaqua had not only somewhat tinctured his son-in-law with Swedenborgianism, _________ 1 Brother Ford's supplications were indeed "powerful." He would jump as high as the table and shotit loud enough to be heard a mile away. "We children," said Aunt Eliza, "were scared when he prayed in the old log house; Father never prayed that way. 10 CAPTAIN HENRY OF GEAUGA as already intimated, but had taught him also the elements of land mensuration and the convenient use of decimals therein. Under such influences the young teacher and surveyor, John Henry, continued in Johnston for a period of nearly four years, during which his wife Polly bore him two sons, christened appropriately Simon Jaqua and John Newton. From Johnston to Bainbridge, thirty-five miles due west, they removed in March, 1823; and for the rest of their lives made their home on the north half of lot twenty-seven, tract three -- a part of Simon Henry's long strip of land, lying remote from his own residence and just west of the Aurora fork of the Chagrin River. Five years later, the father, continuing the partition of his lands among his sons, put this parcel of a hundred acres at John's disposal, conveying it on February 16, 1828, as follows: fifteen acres at the west end, by John's request, to his brother Calvin, in pursuance of some dealings between them; fifty acres at the east end to John himself, for the consideration of one hundred dollars; and the remaining thirty-five acres to the same, for the consideration of love and affection. This ancestral farm of eighty-five acres John eventually conveyed to his sons Simon and Charles. Simon sold his south half to Charles, in whose family accordingly both parcels have since remained. Besides the two sons in Johnston, seven children were born in Bainbridge in the fifteen years from 1826 to 1841: William Ray Babcock, Mary Maria, Martha Ann, Emma Eliza, Charles Eugene, Harriet Eliza, and Edward Everett. Of these, William (or Babcock, as the child's father has it) and Emma died in infancy. Nearly two years after the former's death, John Henry penned this tribute in the back of his Methodist class-meeting record book:

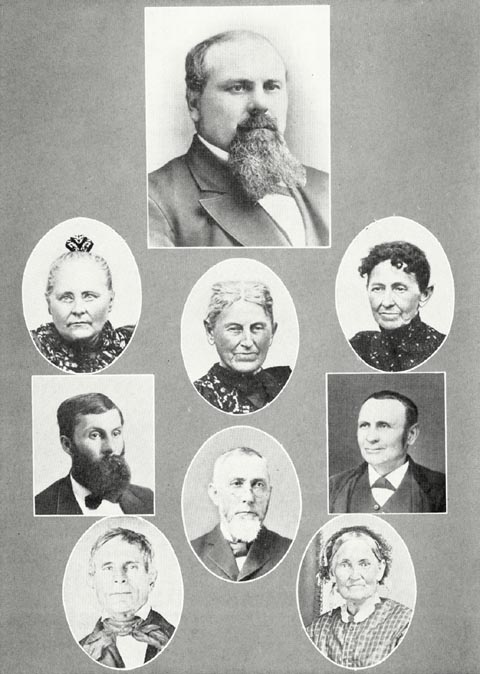

[ facing 10 ]

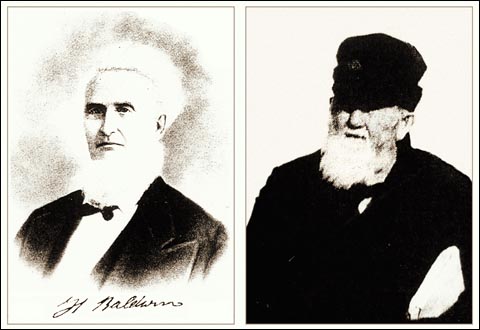

John and Polly Jaqua Henry (bottom) and children: Charles (top) Maria Goodsell and Newton (middle) Eliza Brown & Edward (left) Ann Brewster and Simon (right) STATE IN GRACE AND IN LIFE 11 The same book records the attendance at eighty class meetings from June 28, 1828, to May 1836. 1 The class comprised twenty-one members much of the time; but by deaths, removals, withdrawals, and one expulsion, it dwindled to a third of that number and finally flickered out. Some of the members came from the adjacent townships of Aurora and Solon, over the county lines. The "State in Grace" of each one is marked "B," perhaps for Baptized; the "State in Life," "M" or "S." Heading the lists of names throughout the record are John and Polly Henry. Then follows Joseph Witter (a Revolutionary soldier and one of the guards at the execution of Major Andre) with his wife Hannah. 2 John Henry's worldly condition at this epoch is indicated by a tax receipt of November 30, 1831, which discloses a charge of $1.464 for that year on his eighty-five acres of land, and $0.504 on his chattels; making a total of $1.968, which, less road tax worked, left a balance of $1.33 paid by him in money. Trivial as this exaction now seems, it was then more burdensome than the far heavier taxes of today; and with the growing public needs of the new community, the burden was bound to increase rapidly. Between 1831 and 1835 the tax valuation of this farm rose from $163 to $240, probably implying the erection meanwhile of the split-log house hereinafter described. The tax rate fluctuated from $9 per thousand in 1831, and $5.50 in 1835, to $10.48 1/3 in 1837. The civic side of John Henry's life is further illustrated by a certificate dated April 17, 1830, and signed by Aaron Squire, Simon Henry, and Enos Kingsley, of Bainbridge, as township trustees, appointing him supervisor of highways in District Number 9, a humble but exacting office to which he was probably often called. Teacher's certificates were also issued to him by George Wilber, of Auburn, and O. Henry, on January 21, 1832; by David Shipherd and M. Henry, of Bainbridge, on January 14-19, 1833; and by Nelson Eggleston and S. D. Kelley, of Aurora, on November 8, 1833. For twenty-nine terms, in all, he is said to have taught school, not _________ 1 During this period the conference and circuit were thus officered: presiding elders, William Swayze (1828) and Ira Eddy (1830); circuit preachers, Ignatius H. Sackett and Cornelius Jones (1828), John Chandler and John McLean (1829), Caleb Brown and John Ferris (1830), Thomas Carr and Lorenzo D. Prosser (1833); class leaders, John Henry (1828-1831, 1833-1836) and Jarvis McConoughey (1831-1833). John Crawford, circuit preacher, had previously certified at Bainbridge, on March 5, 1828, "that John Henry is an acceptable member of the Methodist Episcopal Church, and a Class Leader in Cleveland Circuit, Pittsburgh Conference." 2 Also Abraham and Laura Witter, Lucius and Hannah Eggleston, Harvey and Catherine Waldo, and James H. (or J. Harvey) and Cornelia Henry. The last named were neighbors of John Henry, but not akin to him. They are marked as having moved away after the meeting of June 12, 1831, but a relative, Reuben Henry, afterwards lived in the vicinity for many years. Married members, whose consorts apparently had not joined, were Jarvis McConoughey, Fanny Bull, Sally Herrington, Harriet A. Prior, and Lewis Olney. Of the single "State in Life" were William Witter and Elvira Woodward, who, however, were joined in wedlock in 1830; also Amelia M. Bull, Amelia Ann Herrington, and Maria, Sophia, Lucy J., and Eliza Ann Robbins. Abraham and Laura Witter moved 12 CAPTAIN HENRY OF GEAUGA only in his own and surrounding townships, but also, because of the higher pay in older settlements, as far away as Crawford County, Pennsylvania, near the last home of his widowed mother-in-law, Ruth jaqua, and her daughter Drusilla, of whose husband, David McGranahan, uncle of the hymnist James McGranahan, he was very fond. A rough plat, made by John Henry, on February 18, 1833, of Bainbridge School District Number 1, where he lived, locates the farms of his neighbors, Graham, Giles, William Henry, Witter, Squire, Eggleston, Mason, Russ, Waldo, Kent, Marshall, and Benjamin Rush, besides his own homestead. This corner of Bainbridge was about as populous then as it has been at any time since; but the great forest, abounding in wolves, occasional bears and deer, and other wild things, loomed omnipresent, with small, slow-spreading clearings surrounding the log houses of the settlers and connected by threading trails that but tardily attained to the dignity of roads. Said Father, in his obituary of Mrs. Rachel Henry, above cited: The woods were full of game, and the streams and lakes of fish; and when one became sick a ready and curative remedy was found in roots, herbs, or bark. With scarcely any inequality of fortune among the pioneers, envy's tooth gnawed them not. All alike were poor; all struggling towards better things for their children in the years to come. And the children, at least, found happiness in this environment. Born amidst the forest, they grew up in the glamor of it. Unconscious of the limitations to which it subjected them, they knew only the manifold riches of nature's wilds. But not a few of their elders, who had tasted of the fruit of the tree of knowledge, suffered vain regrets for what they had found and lost in the life they had left behind them. Many, never acclimatized in the new country, burned and shook their lives away with fever and ague, or sank slowly beneath subtler and yet more fatal visitations. Even the consolations of their religion of otherworldliness served often but to emphasize the gloom of their life in this world. One source of alleviation of their lot was, however, unfailing: neighborliness and hospitality abounded, and the social intercourse of log-rollings, quilting and husking bees, of spelling schools, training days, church and camp meetings, lawsuits, elections, raisings, weddings, and even of _________ away after the meeting of February 14, 1830; and Harriet A. Prior after February 21. The Waldos and Lewis Olney withdrew or removed, while Lucy Robbins and Amelia Bull were "dropped." Joseph Witter died in February, 1831, and his widow moved away, to reappear later, however, with a Joseph and Esther Witter. In the winter of 1834-1835, Jarvis McConotighey, a mighty hunter before the Lord, who brought haunches of venison from time to time as welcome gifts to the Henry household, "removed to Solon," having sold his farm to Gideon Kent; and Sophia Robbins "removed to Streetsborough class." Lucius Eggleston was "expelled for bad conduct to his wife"; and in May, 1836, Fanny Bull "joined the new divinity men." This crowning apostasy appears effectually to have closed a chapter, which is thus minutely reproduced as helping to make clear the surroundings amid which the subject hereof was born, some six months before. TRAITS OF PARENTS 13 funerals, afforded variety to toilsome lives. Every device to relieve the somberness of existence was eagerly welcomed unless forbidden by their moral code. Many of the pioneer women and most of the men sought and found solace in smoking, and to Polly and Rachel Henry, Deborah McConoughey, and many other of the neighboring housewives, when they forgathered for an afternoon visit, clay pipes and tobacco were no less important adjuncts of the occasion than their knitting. John and Polly Henry were not ill mated. Both were God-fearing and home-loving, fond of reading and of the society of good people. In most other respects their temperaments were complemental. Her democracy brooked no patronizing, and her effectual foil to such offending was either a plainlv feigned surprise at unfounded pretensions, or else a naive blundering on skeletons in the offender's closet. Her husband, no less sensitive, but more reticent on such occasions, preferred to shtin those who gave him offence. Like the rest of the Henrys he was given to nicknaming. To his children who "peeked" over his shoulder, or otherwise manifested undue interest in business not their own, he would shout, "Lyman Fowler, go and sit down." If any of them talked too much or too freely, "Joel Giles, be still." His son Simon's father-in-law, Mr. Wesley Whipple, was always "Old Crescent" after he had presumed to explain to Schoolmaster John Henry how to spell "Crescent City." Grandfather called his daughter Ann "Skit" from the agility with which in girlhood she eluded Father's playful pursuit by taking a tremendous leap through one of the open windows of the old log house. A little later, Henry Brewster, triumphing over all the rest of her many suitors, was brevetted "The Little Corporal," for his resemblance to Napoleon in frame and stature and in accomplishing whatever he undertook. The name "Captain Jaqua," which Grandfather applied to his son Newton, long remained uninterpreted, despite the other children's searching inquiries, until Uncle Edward came home on furlough from the army, when, said he, Father was so glad to see me that in the woods I cautiously asked him for the thousandth time why that nickname to Newton. "Why, I don't know, unless it was that Newton was so full of roguery." Beneath the jest lurked this hint of seriousness: Grandmother always maintained that her father was "more spiritual" than her mother; but Grandfather, having discerned some real or fancied limitations on Captain Jaqua's spirituality, preferred the sound piety of his mother-in-law. Truthful always, and plain-spoken when plain speaking was required, Grandfather Henry impressed one as habitually "Careful in speech, forbearing toward men, and faithful to God." Of this draft of his epitaph, which, after his death in 1869, his son Charles had worded, General Garfield, the friend of both, on its submission to him for criticism, exclaimed, "That is splendid, Charlie; I can suggest but one change: for 'men' read man; it is more comprehensive." 14 CAPTAIN HENRY OF GEAUGA Alike conscientious, John Henry was a moralist; his wife, a casuist. Doctor Shipherd often said, "John and Orrin Henry were the most honest men I ever knew." And Orrin, in his old age, wrote to his nephew Charles, "I always thought my brother John had a call to preach." As postmaster at Pond, for so the local railroad station and post office, now Geauga Lake, was called, John Henry, during this decade of his later years (March 11, 1857, to October 10, 1867), kind-hearted and obliging though he was, could not be induced to violate the Government's regulations by a hair's breadth for the accommodation of anyone. But his wife would take the locked mail pouch from her husband's hands, and, despite his mute protest, slip into it letters brought to the office by anxious patrons too late for regular posting. "It was a queer post office," said Mrs. Mary (Henry) Kennedy: "Have you any letters for me, Uncle John?" his niece Adelaide inquired. So, too, as wife and widow, John Henry's helpmate scrupled not, among even her adult children, to appropriate a Peter's plenty to the relief of a needy Paul. Though never extravagant -- how could she be? -- credit to her was always as good as cash, especially in aid of her children. To each of her family in turn, even when they stood at cross purposes, the sympathetic mother and loyal wife lent her whole-souled support. The one in trouble at the moment always enlisted her aid. Ever resolute and aspiring, in contrast to her husband's resigned acceptance of their lot in life, for her it was emphatically not enough that they should "barely live and be content." He, on the other hand, never robust in body nor strenuous in action, implicitly accepted, not as a mere convenient pretext, but as from the divinely inspired word, his Master's injunction: "Take no thought for your life, what ye shall eat or what ye shall drink; nor yet for your body, what ye shall put on. Is not the life more than meat, and the body than raiment?" His brother William, thrifty and blunt, complaining of breaches made by cattle and Chagrin floods in John's part of their line, was wont to denounce the latter's "shiftless Jaqua fence" -- a double thrust, aimed not only at John's ineffectual poling of the river, but also at the enervating cause thereof, "the filthy tobacco habit." This vice, originating with the Jaquas, had ensnared even his own wife Rachel, whose secret supply of the weed he once slipped angrily into her teakettle, and at another time besprinkled with gunpowder, to the acute discomfort of the smoker and her family. In the following quatrain he frequently proclaimed his antipathy to my Lady Nicotine: JOHN HENRY, SURVEYOR AND SCHOOLMASTER 15 And from the devil doth proceed; It picks your pocket, burns your clothes, And makes a chimney of your nose. Thus as time went on, the amenities of fraternal intercourse between these brothers devolved more and more upon their wives and children. John Henry's avocations, as schoolteacher, surveyor, and later as postmaster, interfered necessarily with his efficiency as a farmer. I have the field notes of over forty surveys made by him between 1833 and 1846 in Bainbridge, Russell, Auburn, Troy, Aurora, Solon, and elsewhere; and these are doubtless but a portion of all that he made. On one of them is marked, "Charge $4.00," a rate of pay that could hardly yield a competence. His son Edward wrote me that John Henry was "commissioned surveyor by the fourteenth governor of Ohio," Wilson Shannon. "This commission," he added, "I let Governor McKinley or Governor Hayes take as a curiosity, and I cannot find it." The record in the governor's office at Columbus discloses that on October 29, 1840, when the division of the county had created vacancies in some of its offices, a commission was issued to John Henry as county surveyor of Geauga County for three years, thus qualifying my father's impression that he "was elected county surveyor one or two terms, and declined to serve any longer, as he lived twenty-one miles from the county seat." But the courts sometimes appointed him to ascertain boundaries, lay out highways, or partition estates. I have also five of John Henry's neatly kept teacher's records, the earliest of which is marked in his fine hand: "School journal, Commencing Nov 24th, 1834, in the Southeast corner of Bainbridge; Enos D. Kingsley, Park Brown, Thomas Smith, Directors; Horace Crosby, Treasurer; John Henry, Teacher; compensation 12 Dollars per month." The school was in session six days each week, Christmas and New Year's included, and it closed on February 22, 1835. 1 During the next winter he taught in Solon, beginning on December 10, 1835, eleven days after the birth of his son Charles, and continuing, Saturdays and holidays included, and with only an occasional day missed to attend to surveys or other urgent business, until March 8, 1836. 2 The other three records in my possession cover terms which he taught in Pennsylvania during the winters of 1839-1840, 1840-1841, and 1842-1843. Many other such journals of his have disappeared. Trusting in Providence no less implicitly than her husband, Polly Henry's optimism was commonly translated into action. Hers was decidedly the more _________ 1 The pupils were E. D. Kingsley; George, Robert, and Thomas Smith; G. Smith, Jr. Also, William Russell, Horace Crosby, Park Brown, Samuel Creager, William Burgess, Seymour Dodge, Abner Bingham, David Baird, John Scouten, Alexander, Jr., and Russel Osborn, Cornelius Bowerman, and Susan Barber, the only girl! 2 His pupils here were E. and John Trowbridge, W. Stannard, G. Mason, A., H., and W. Dunwell, Wid and J. Baldwin, A. and William Witter, Moses Shaw, Festus Merry, Warren Howell, Charles Warren, H. Phelps, J. Bartlett, and Jarvis McConoughey. 16 CAPTAIN HENRY OF GEAUGA intrepid spirit; her temperament more buoyant and volatile. If the tea was out, or they lacked money to pay taxes, his reply to her inquiry as to what they were going to do was apt to be "I don't know any more than the dead." But she would turn to her loom, finish a bolt of rag carpet and, throwing it on the old mare's back, ride with it to Solon, Aurora, or even to distant Warren, returning triumphant in due time, the crisis met. When the wolves followed her through the forest, she would sing in clear, ringing tones a Wesleyan hymn, and the wolves would stop howling and listen, but keep on following more distantly to the clearing in the woods. Doctor John Hatch, of Aurora, always maintained that his Aunt Polly -- he was her nephew by marriage -- had a "voice like an angel's, the sweetest he ever heard;" and I myself have heard her sing, when she was over seventy years old, in tones even then so melodious as to confirm the verity of his testimony. In all the Methodist meetings great and small which she attended in the early days, she was commonly the one to be called on or to volunteer to lead the singing. At church, people who did not know she was present would recognize her voice in the congregational chorus of Rock of Ages, Happy Day, the Missionary Hymn, or any of the grand old numbers, -- Nettleton, Amsterdam, Ardon, Bethany, and scores of others. "The Aurora folks," said my Aunt Ann Brewster, "often used to get her to sing there." Her appearance, too, was captivating. Mr. Austin Beecher, a competent if somewhat carnal-minded judge of female beauty, often asserted that in her youth she was one of the handsomest women be ever saw. I can answer for the regularity of her features and the brightness of her black eyes down to the time of her death. Added to these charms was her lively imagination, which lifted her constantly above the hardships of pioneer life. Though intensely practical in every-day affairs, she was no stranger to the world of dreams and romance. She had the full measure of superstition of those early days. To spill the salt was an omen of misadventure; to drop her dishcloth a sure sign of visitors. Of similar import was the crowing of a rooster on the doorstep or the floating of tea grounds in the cup. During the malaria epidemic of 1846 she, the mainstay of her stricken family, feeling that she at all hazards must be rid of the disease, resorted at last to mild diablerie: Now I'll tie you up to this old beech tree. The Bible was to her a book not only of divine revelation but of pious divination as well. Special providences were the constant attendants of family and neighborhood life. Dreams were as plainly significant to her as to Joseph of old. Her vision tales of "The Ox with Great Horns," and "The Two POLLY HENRY'S THRILLING TALES 17 Balls of Fire," held her children and grandchildren spellbound. Deaths especially were foretokened by dreams of the grim horseman and his pale steed. Thus she suffered double agonies when, as she averred, the dread visitor, so heralded, actually crossed her threshold. Conversely, "Dream of the dead and you'll hear from the living," was a favorite aphorism, its prediction seldom or never failing. The characters of fiction, moreover, in her vivid rehearsal of Scott's and Cooper's tales, donned robes of flesh so real that in after years, as the children came to read the books for themselves, the stories of "Di Vernon," "Harvey the Spy," "Leatherstocking," and all the rest, seemed like biographies of veritable persons. Her husband, John Henry, often reproving her for minor inaccuracies, could not only repeat from memory every word in Webster's Spelling Book when he presided at spelling schools, but he could recite the whole of Scott's "Lady of the Lake," much of Goldsmith's "Deserted Village," and all or large parts of divers other poems. She, however, could lift clear of the printed page and marshal in living pageantry "Fitz-James" and "Roderick Dhu" with all their border hosts. "Her account of the great meteoric shower in 1833," declared her son Edward, "was thrilling." It seemed as though the stars of heaven were all falling, and everyone but her husband, John Henry, thought the world was coming to an end. The effect on some of the neighbors was for good. Two or three wicked swearing fellows became almost converted to God, and behaved themselves for a long time. More meteors would have made them go to the mourners' bench. 1 In conversation her vivacity was such that her words and thoughts sometimes tripped over one another. On the road to "the Center," according to a story which has certainly not deteriorated in the telling, she one day late in life reined in her pony at Charley Chase's blacksmith shop and, hailing the horseshoer, said, "I want you to set Dolly's shoe. Have you heard that George Shipherd's baby is dead? It has gone clickety-clack, clickety-clack, all the way up." Calling upon Mrs. Amanda Briggs, who had just finished baking a pound-cake, and whose child stood clinging to her skirts, Grandmother exclaimed, "Oh, what a beautiful cake! And what a beautiful child!" Then inquiringly. "Raised with empt'in's?" At another time, when one of her granddaughters, Cora or Florence Brown, made a new kind of cake at her house, Grandmother extolled it as being "so moist and so dry," meaning doubtless that it was neither crumbly nor heavy. An inveterate matchmaker and gossip, she was by no means a trouble- breeder; for she said to people's faces, frankly and with impunity, what others would only whisper behind their backs. When one of the same neighbors took his mother's hired girl to the county fair and stayed two or three _________ 1 One of the neighboring Henrys, a very intelligent man, unrelated to Father's family, is said to have even got his suit or robe ready to go up in the general ascension. 18 CAPTAIN HENRY OF GEAUGA days, the girl petulantly denied Mistress Polly's suggestion of a runaway marriage; whereat her interlocutor replied spiritedly, "It looks like the game without the name." The young man's mother, at another time, came weeping and wringing her hands to tell Grandmother that her son was drafted, and cried, "What shall I do?" Grandmother had three sons at the front already. But the oldest, residing nearby with his family, still remained. So she exclaimed cheerily, "Why, maybe Simon can go in his place!" Those who were in sickness or trouble knew well her neighborly kindness and tender ministrations. It became such a religious habit with her to go to funerals, that in later years she was wont to attend them even when her acquaintance with the households which death had invaded was but slight. Her own death from pneumonia on January 21, 1881, was due to imprudent exposure to inclement weather on such an occasion. She was a persistent letter-writer, and all of the Henry kindred who had moved farther west before the Civil War, including one who sided with the South in that conflict, were long kept in touch with their relatives in Ohio through her unfailing diligence as a correspondent. Her sympathies were so keen as often to engross her mind to the exclusion of all other considerations, however important. This is illustrated by Father's account to his grandchildren of "a little incident of childhood days." If anything got into the eye and gave great pain, it was believed that a louse put under the eyelid would relieve the intense suffering. Cousin Jehu Brainard and his wife Maria lived in the old round-log house adjacent to ours. Cousin Maria one day began to scream with pain in her eye. Your great-grandmother, full of sympathy, got a little tin box ["her round black snuffbox, " said Aunt Ann, "with flowers on the cover"] and sent me up the hill as fast as my young legs could carry me. Brother [a grandchild] could not run faster or talk faster. Almost out of breath, I said to Mrs. G--, "Cousin Maria is in awful pain in her eye. Mamma wants a louse to get it out." With a look of haughty scorn I never forgot, she replied, "Go home and tell your mother to comb her own darn young 'uns heads." I returned with empty tin box, wondering why she had treated me so scornfully, as we had always been the best of neighbors. Long years afterwards, when "Aunt Polly," as the neighbors called her, lived all alone in her widowhood, declining the invitations of her children to live with them, I recall her smiling face at the door and her cheery greeting, "Oh you deary!" when the clicking gate announced a grandchild's coming. I remember the old-fashioned flowers in her dooryard, with its bachelor's buttons and marigolds, its meetin' seed, its yellow dahlias, larkspurs, and roses, its "pinies," poppies, and pansies, and its wonderful perennial shrubs, the "tree of heaven" and the "tree of life." I can still taste the mellow russets and pippins in her orchard below the house, and the pies and the peppermint drops from her cupboards. I fancy myself again driving IN HEAVEN'S ENVIRONS 19 up her cows, Old Star, Little Star, Beauty, Spot, 1 and the rest; or bringing her mail from the post office-letters from children or from cousins in the West, the Guide to Holiness which she read alone, and Robert Bonner's New York Ledger which, as she sat knitting, sewing carpet rags, or paring apples, I was always glad to read to her, with its thrilling tales by Sylvanus Cobb, Jr., or Mrs. E. D. E. N. Southworth. I see her now sitting by her fireside beneath the festoons of boneset and lobelia, wild berries and dried apples, that adorned her ceiling, and reading her worn and dog-eared "Testament and Psalms," all stained with tears and candle grease. I scent the pungent wholesome savor of her sage, catnip, and pennyroyal. I hear the clang of her loom at the head of the stairs, and see the swift-darting shuttles, as with aged but still deft hands and feet she wove into handsome carpet the rags she had patiently cut and dyed and sewn. My dear grandmother! She surely trod the road to heaven, for it was in heaven's environs that her children and their children always found her. _________ 1 One cow was curiously yclept "Stonewall Jackson," doubtless by Grandfather. |

|

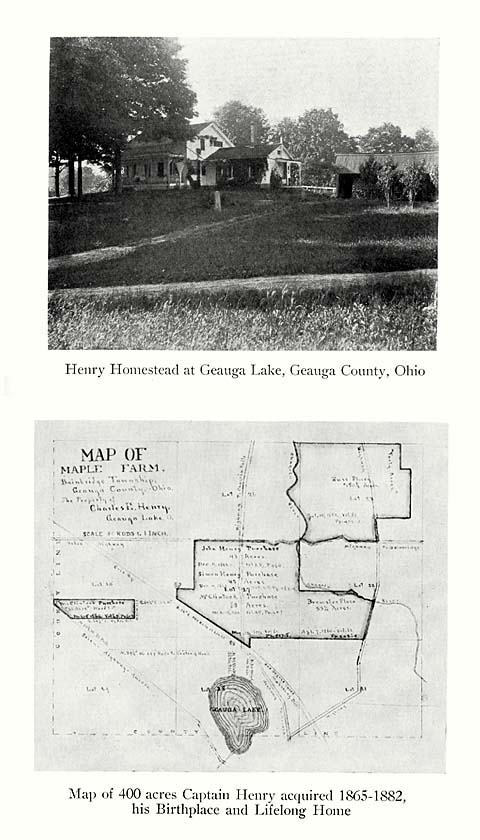

[ 50 ]

Allusions already made herein, to the pioneers' habit of religious discussion, to the "Holmes fog," to the "Campbellite" reformation, to the "New Divinity" men, and finally to the Mormons, suggest certainly the existence of an unusual religious ferment. Among the many Disciples of Christ, or "Campbellites," on the Western Reserve, who were attracted for a season into the Mormon fold, Sidney Rigdon stood easily first. Ambitious, erratic, and eloquent, but not over-scrupulous, he became at once the brains of Mormondom. Grandfather John Henry maintained that he probably compiled the Book of Mormon while sojourning one winter (1825-1826) 1 in Bainbridge. In his quarters south of the Center, he seemed always to be writing, sometimes far into the night; and though he received courteously all who called, he would first lift the lid of his desk and lock his mysterious manuscript away therein before admitting them. Some years of foreknowledge of the appearance of the Book of Mormon in April, 1830 (it was ready for the press in June, 1829), is, moreover, expressly ascribed to Rigdon by various contemporaries and particularly in a letter from Darwin Atwater, of Mantua, to the author of Hayden's Early History of the Disciples in the Western Reserve, quoted at pages 239 and 240 of that work. In a communication to the Cleveland Leader, which appeared in its issue of Sunday, March 14, 1886, Father wrote from Geauga Lake, under date of March 9, the following account of Rigdon's connection with "The Spaulding Manuscript and Book of Mormon." Other engagements prevented my hearing President Fairchild's lecture last evening upon the Book of Mormon and its relation to the Spaulding__________ 1. Linn's The History of the Mormons, p. 60; Hayden's Early History of the Disciples in the Western Reserve, p. 191. SIDNEY RIGDON'S BOOK OF MORMON 51 manuscript. It has been the popular belief among older citizens of the Reserve, and especially among those who had personal contact with early Mormonism, that the Book of Mormon was made up in part from the Spaulding document, and yet there was no direct or positive evidence to prove it. From some facts and incidents connected with the career of Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon when they were in Geauga and Portage counties preaching their alleged new gospel I came to the conclusion some years ago that the Book of Mormon was the work of Sidney Rigdon, with perhaps some changes and additions by Smith or others. So far as I know, these facts and circumstances have never been published. The truth or falsity of the Spaulding matter in no manner affects them, and they came to me in a way that leaves no doubt in my mind that the Book of Mormon, or a large part thereof, was written by Rigdon within two miles of the spot where I am now writing. 52 CAPTAIN HENRY OF GEAUGA silence and professions as a prophet. Those who were not awed by the glamour of mystery became convinced of one thing, that he was a man of little or no education, while Rigdon was a fine orator, a fair writer, and among the men of that day a good scholar. Edward H. Anderson, the authorized compiler of A Brief History of the Church of Christ of Latter Day Saints, declared that Rigdon embraced their faith about November, 1830, in or near Kirtland, Ohio; and going straightway to New York "to inquire of the Prophet what was the will of the Lord concerning" him, he "was retained to assist Joseph as scribe in the inspired revision of the Holy Bible, which work was begun just before the close of the year 1830." With Smith, Rigdon returned to Ohio about February 1, 1831, and that summer they made a short trip to Missouri. Coming back to Ohio, they lived in Hiram, Portage County, until the following April, when they again visited Missouri, both having been tarred and feathered in Hiram, during the night of March 24-25, 1832. 1 They returned to Kirtland in June __________ 1. See the Geauga Gazette for April 17, 1832, in the Western Reserve Historical Society. (Misc. No. 21.) WHIG CAMPAIGN SONGS 53 of that year, and according to Anderson completed their "revision" of the New Testament on February 2, 1833. In view of these dates there seems to be no warrant for the conjecture that this revision, rather than the Book of Mornton, was the work on which Rigdon labored in Bainbridge in 1825-1826. The impress of Mormon proselyting during the next few years, though visible in Bainbridge, was less apparent there than in some of the surrounding towns. None of the Henrys was inveigled into the movement, although in 1837 [sic - 1838?], when the Mormons'cavalcade passed through Bainbridge on their journey to Nauvoo, Illinois [sic - Missouri], and camped on the Case farm in Aurora, Carlos Henry as a boy came near going with them, and John and Harriet Squire, near neighbors, did go -- the latter marrying the Mormon Elder Snow. The Abolition movement struck yet closer home. The Henrys, for generations opposed to slavery, aligned themselves with the Federalists first, and then with the Whigs, while those parties lasted. "They were all," said Father in a letter from "Home, October 21, 1904," "disciples of Washington, Hamilton, Webster, Clay, and Corwin." Though too young to remember much about the "Log Cabin Campaign" of 1840, Father must often have sung in boyish play, as he sometimes did in after years, the stirring campaign songs of the Whigs: All the country through? It is the ball a-rolling on For Tippecanoe and Tyler, too, And with 'em we'll beat little Van, Van, Van is a used up man; And with 'em we'll beat little Van. Oh, where, tell me where, was your Buckeye Cabin made? 'Twas built among the merry boys who wield the plow and spade Where the Log Cabins stand in the bonnie Buckeye shade. __________ 1. Both are quoted in full in Howe's Historical Collections of Ohio, Vol. 2, pp. 707-9. Each had many stanzas. 54 CAPTAIN HENRY OF GEAUGA

(view enlargement of Henry home photo) (view enlargement of map image) Pages 432-735 not transcribed. |

|

Frederick A. Henry

(1867-1949) Centerville Mills... (Mayfield, Ohio: 1962 -- from 1946 MS) |

|

Frederick A. Henry's 1942 book Captain Henry of Geauga

|

C E N T E R V I L L E M I L L S AND THE O L D C H I L L I C O T H E R O A D BY FREDERICK A. HENRY

October 1, 1946

Reproduced for Mayfield City Schools Camping Program -- April 1962 |

Frederick Augustus Henry (1867-1949) Frederick A. Henry's Biography of his Father In his 1946 historical sketch of Aurora and Bainbridge townships, Frederick A. Henry records these interesting conclusions: "[speaking of the Aurora Baptist Church, 1834-1869] ...It seemed as if every new or competing religious movement in the vicinity gained one or more recruits from among these Baptist brethren. In 1837 when the Mormons' cavalcade started from Kirtland along the Chillicothe Road for Nauvoo, Illinois, they camped the first night on the Case farm a half mile south of Centerville. The church record shortly afterwards notes: 'February 3, 1838. Albert Smith excluded for joining the Mormons.'" In an earlier version of this account, published on page 53 of his 1942 biography of his father, Captain Henry of Geauga, Frederick A. Henry provides the same information that he gives in the first paragraph above: "when the Mormons'cavalcade passed through Bainbridge on their journey to Nauvoo, Illinois [sic - Missouri], and camped on the Case farm in Aurora, Carlos Henry as a boy came near going with them, and John and Harriet Squire, near neighbors, did go -- the latter marrying the Mormon Elder Snow." For some reason Mr. Henry did not mention Albert Smith having joined the Mormons' passing "Kirtland Camp" when he wrote his 1942 published account. The Otis P. Case farm, where the 1838 "Kirtland Camp" Mormons paused in their southward journey, was located just south of the Bainbridge-Aurora township line, north of Aurora Center, on Chillicothe Road (Ohio State Highway 306). Frederick A. Henry's information regarding Sidney's Rigdon's 1826-27 "sojourning in Bainbridge" evidently came from the recollections of his father, Charles Eugene Henry (1835-1906), who wrote about the same subject in 1886. Frederick's father (who had not yet been born during's Rigdon's residence at Bainbridge) in turn, derived the information from conversations with his own father, John Henry (1796-1869) and more particularly George Wilber, a life-long resident of adjoining Auburn township.  Frederick A. Henry's Grandfather John Henry Had Frederick A. Henry's grandfather left behind any written or published account of Sidney Rigdon's life in Bainbridge, such an historical momento would indeed be a valuable one. As it now stands, there is no known account of Methodist Class Leader John Henry's interaction with the recently defrocked Baptist parson, Sidney Rigdon, lately relocated to Bainbridge from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It is not likely that relations between the two men were particularly cordial. Rigdon himself supplies a small glimpse into this obscure portion of his early religious career: [In 1826 Rev. Rigdon]... removed to Ohio as an Independent Baptist, preaching what he pleased and contradicting whomsoever he pleased. He himself stated that not unfrequently he would attend a service and take his seat among the congregation, and after the sermon arise and ask the liberty of adding a few remarks, and then quote passages of Scripture to show the erronous doctrines which the preacher had just uttered, and close by inviting the congregation to come and hear him at his next appointment. This kept the community in a ferment and secured for him crowded houses. He seemed just on the point of forming a new sect which should overthrow by learning, logic and eloquence all the creeds and religious systems of the world!! Dr. Carl N. Brewster's Theory: No doubt Rev. Rigdon's actions did keep "the community in ferment," all through the southwest corner of Geauga and northern section of Portage counties. In an 1945 manuscript entitled, "Did Sidney Rigdon write the Book of Mormon?" Professor Carl M. Brewster (a relative of Frederick A. Henry quotes from page 143 of the 1880 Pioneer and General History of Geauga County, as follows: "Joel S. Giles came from Warsaw, New York, to Bainbridge... [his] farm [was] situated near the southwest corner of the township... [on the edge of] Geauga lake... Joel Giles, sr., and wife, were members of the Baptist church, which was organized at an early day in that part of the township. Services were held first in private houses, and later in a school-house. The church propsered for a few years, but was eventually broken up by a wolf in sheep's clothing (Sidney Rigdon, of Mormon notoriety), who entered the fold, and the sheep were scattered abroad." If Sidney Rigdon's unorthodox preaching of 1826-27 alienated many of his fellow Baptists, the modern reader can only wonder what sort of effect the man must have had upon the local Methodists and Presbyterians. No doubt Reverend Rigdon found more sympathetic audiences a few miles further east, in Auburn and Mantua. He was respected enough in the former township to be called upon to preach a funeral sermon there in May of 1822, when he was residing in Pittsburgh, but perhaps happened to then be visiting his wife's relatives in neighboring Trumbull Co., Ohio (see the 1885 Isaac Butts statement in Deming's Naked Truths newspaper). Or, perhaps Issac Butts' memory of his brother's death was off by a year, and Rigdon was called over from Trumbull Co. to preach the funeral sermon before he moved to Pittsburgh. At any rate, Sidney Rigdon appears to have been a well-known religious figure in Auburn during the 1820s. His close interactions with Auburn settlers who had come there from Palmyra and Manchester must be accepted as a solid fact -- and a fact that dates to several years prior to the publication of the Book of Mormon in the former New York town. As already stated, John Henry left behind no written nor published recollections of Sidney Rigdon, so his memories of the defrocked Baptist preacher evidently came down to cousins Frederick A. Henry and Carl M. Brewster only as oral family traditions. Frederick's father, Charles E. Henry, passed along what appears to be more substantial oral history, in his 1886 letter to the Cleveland Leader. Both Frederick and Carl make this letter the certerpiece of their respective claims for Rigdon's involvement in the creation of the Book of Mormon. Charles E. Henry's re-telling of George Wilber's 1826 experiences with Sidney Rigdon are made doubly interesting by the fact that Mr. Wilber was a long-time resident of Auburn. Wilber undoubtedly lived among and personally knew most of the Auburn settlers whose families came from the Palmyra area. For example, Frederick A. Henry lists George's name as being recorded in the same Henry Brewster account book that held the names of Christopher M. Stafford and "Grandfather" John Henry, (see Captain Henry of Geauga, p. 73). The reported recollections of George Wilber, giving an account of the Rev. Sidney Rigdon and Joseph Smith. Jr. interacting together in Bainbridge township, in what must have been either 1826 or early 1827, are probably authentic. Whether or not they are reliable is another matter, however: it is unfortunate that they only come down to the modern reader, as Henry family tradition, via "Captain" Charles E. Henry. The same might be said of the reported recollections of Dencey Thompson Henry (who was the 1827 bride of "Grandfather" John Henry's nephew, Orrin P. Henry, Sr., as well as a nursemaid in the Rigdon home at Bainbridge). Dencey's potentially invaluable reminiscences of life in the Rigdon home come to the modern reader as hearsay, via her son, Orrin P. Henry, Jr. Carl M. Brewster, when he was writing his 1945 manuscript concerning Sidney Rigdon, evidently never had Dencey's recollections to use in "triangulating" the suspected presence of Joseph Smith, Jr. in Geauga Co., Ohio during 1826-27. Dr. Brewster did have the first of two reminiscences left by the neice of Sidney Rigdon's wife available for his consultation, however. In the 1879 publication of her Rigdon recollections, Amarilla Brooks Dunlap stated: "When I was quite a child I visited Mr. Rigdon's family. He married my aunt. They at that time lived in Bainbridge, Ohio. During my visit Mr. Rigdon went to his bedroom and took from a trunk which he kept locked a certain manuscript. He came out into the other room and seated himself by the fireplace and commenced reading it. His wife at that moment came into the room and exclaimed, 'What! you're studying that thing again?' or something to that effect. She then added, 'I mean to burn that paper.' He said, 'No, indeed, you will not. This will be a great thing some day!' Whenever he was reading this he was so completely occupied that he seemed entirely unconscious of anything passing around him." In a c. 1881 recollection (of which Brewster was evidently unaware and does not cite) Amarilla Brooks Dunlap communicated that she "lived under the Rigdon roof at that time" (while the Rigdons were at Bainbridge) and that the situation in the family was "greatly to the concern of Mrs. R. for her husband's health," because "Mr. Rigdon was for some months secretly and sedulously engaged over a mysteriously and carefully guarded manuscript of a very questionable character."

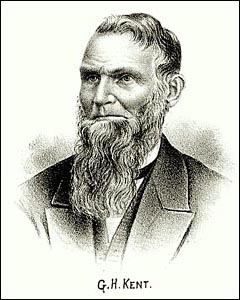

Rigdon's 1826 neighbor George Wilber Possibly the future Mormon prophet did come to Auburn during 1826 and/or 1827. It was a place far removed from his Pennsylvania legal troubles and from disgruntled money-diggers, such as Samuel Lawrence, in the Pamyra area. If Smith did visit Auburn during the mid-1820s he would have found the families of former neighbors and friends living there. And five miles to the west lived the highly controversial Rev. Sidney Rigdon, of course. Carl M. Brewster's reliance upon old family traditions may not have been a total mistake -- but his conclusion that Smith accompanied Orrin Porter Rockwell to that region, to visit with Rockwell's relatives, must be a "red herring" on an otherwise profitable trail for historical inquiry. Information from Local Residents: One of the earliest families to settle in Bainbridge township was that of Gamaliel Kent, Sr. (1768-1831) who arrived in Bainbridge in 1811. The 1880 Pioneer and General History of Geauga County provides the following information on this family's early mercantile venture, at the corner of Chillicothe Road and Taylor-May Road: "Mr. Kent and son, Elihu, purchased the first dry goods and groceries offered for sale in the township. The stock of good was very limited in quantity and variety, consisting of such articles as were considered indispensible. Some were sold on credit, and the accounts were written with chalk upon the side of the house. Paper was not easily obtained at that period. The business was very soon abandoned."

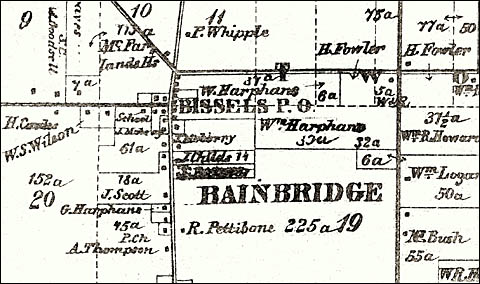

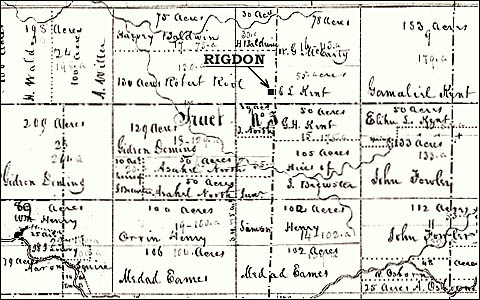

Sidney Rigdon Cabin Site, with Kent Store across the Road, to the East The Kent family's first dry goods store was located across Chillicothe Road, either immediately east of Sidney Rigdon's Cabin, on the property of Elihu L. Kent, or perhaps at the southeast intersection of Taylor-May Road and Chillicothe Road, on property owned by his brother, Gamaliel H. Kent. Elihu L. Kent died in 1827 and his death may have led to the closure of the Kent store on Chillicothe Road. One of Gamaliel Kent, Sr.'s surviving sons, Alexander Edson Kent (1802-1882), was evidently also employed in the family's short-lived dry goods and grocery store. His recollections of Sidney Rigdon's 1826-27 residence in Bainbridge were relayed to James T. Cobb, in a Dec. 17, 1878 letter written by his son Alexander Gamaliel Kent (1845-c.1900): I have just returned from my father [A. E. Kent] where I have endeavored to find out dates as far as feasable in regard to matters of which you ask. When I first wrote you I think I told you that father thought that Rigdon was a regular preacher here for more than one year. I find on looking over his old books more thoroughly that there was an account[,] the first date [of which] was April 4th 1826. Also found accounts in nearly every month, the last one being March 17th 1827. The artickles were butter, sugar, beef, pork, candles, wheat, oats and such artickles as would be needed for the support of family. Father done considerable tanning for him in May 1826. He says that Rigdon use[d] to preach occasionally in town before he became a regular preacher but could not say when he lived there, but is quite sure he did not live in Pittsburgh, and did not come direct from Pittsburgh here. And is quite sure that he did not leave town before the spring of 1827. Father says that he knows that he [Rigdon] lived here while he was making this account. And I think there is no doubt that he came to Bainbridge to reside in the spring of 1826 and went away in the spring of 1827. He live[d] in a little house built for him about a mile south of the center of the town, and the mound still shows where it was... " (original document in the Theodore Schroeder Collection, University of Wisconsin -- Madison Library),