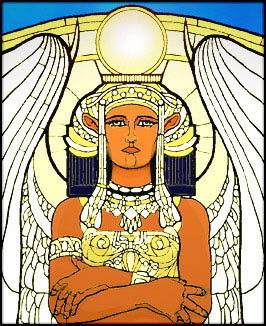

THE RETURN OF As humankind struggles into the 21st Century many of us also struggle to glimpse the face of God anew. But what will this Divine Being look like in the 2000's? The limitations inherent in trying to portray godly imagery have been known since the days of Akhenaten and Moses, but we still strive to see "the face." This adaptation of an old German picture is a rough attempt to portray a Hathor somewhat removed from her Egyptian form but still accompanied by enough original symbols to make her easily recognizable in our day and age. In this image Hathor's cow horns have been moved from their usual position and expanded to form part of her halo. The uraeus around the Aten is now a simple band. These changes reduce Hathor's theriomorphic iconography and help bring her into focus for the modern eye. The addition of wings recalls both Hathor's headdress plumes and the ancient symbol of the winged solar disk; but mainly they reduce the gap between Hathor's traditional appearance and the divine/angelic symbolism of monotheistic religions. Here the Golden One is the modern, personified "House of the Aten," manifesting the radiant glory which at once reveals and conceals Divine Nature. HATHOR AND THE HORNS OF POWER Hathor's horns in the image were intentionally retained and positioned about her entire face in order to convey visually the godly phenomenon of a "horned countenance." Such horns can be compared to the radiant outer aureole of a Buddhist or Judeo-Christian-Islamic halo. In nature comparable analogs can be found in the ring of light surrounding a total solar eclipse or the "sun dogs" which accompany the solar disk when viewed through a sky containing suspended ice crystals. Another solar "horn" is that upper curve of the disk seen on the horizon at the first moment of sunrise. The latter symbol is especially appropriate for Hathor, the goddess who gives birth to the Aten and inculcates it with its stellar power.Hathor's horns are more than a simple halo, however. They are also symbolic of the glorified countenance or illuminated face of the Golden One. This glory has resonances in the "lady clothed in sunlight" aspect of certain Mesopotamian and Canaanite goddesses (some of which are pictured as having bovine horns). Interestingly, the same phenomenon was recently pointed out by Benjamin Scolnic as an explanation for the "horned Moses" found in the book of Exodus ("Moses and the Horns of Power," Judaism, vol. 40, Sept. 1991). Scolnic traces Moses' horned face back to the same Egyptian mythology and symbolism which is invariably associated with the major Egyptian deities, like Hathor. A quote from Scolnic shows the event context for Moses' developing such horns: "...we begin to wonder if Moses is not 'horned' as a divine response to the idolatry of the golden calf incident. The golden calf is the sun-god, the child of the sky-goddess who was a cow. The golden calf had horns. Now Moses is horned as well, horned with a radiance that mocks the physical horns of animal idolatry."

Although the Egyptians did sometimes use the image of a young, spotted bull-calf to symbolize the rising sun, it is more likely that the golden calf of the Israelite exodus was the god Ihy, divine son of Hathor. There is better justification for identifying the calf fashioned by Aaron with the perpetual juvenile Ihy than there is in looking to bovine aspects of Apis, Horus, Ra, or Amun. Alison Roberts points out this fact in her 1995 book Hathor Rising (Totnes, UK: Northgate, pp. 29-32), where she demonstrates how Ihy's young bull nature was sometimes coupled with additional, jackal-like attributes. The jackal nature, in this instance, is that of the animal-god, Up-Uaut -- who led the departed souls of Egyptians through the desert of death. The godly calf, Ihy, in assuming this jackal aspect, became the proper magical guide for Egyptians trabeling in the wastes of Sinai, the eastern land where Hathor daily gave birth to the solor orb. The golden-calf worshippers depicted in the Israelite exodus story were in desperate need just such a magical guide, as they made their way through the trackless wilderness of Hathor's eastern domain, plodding along on a communal pilgrimage to the "promised land, a frightening trek which at any moment might degnerate into a death-march. Although Moses had brought the refugees as far as Mount Horeb, he was not yet prepared to lead the people on the unknown paths beyond the vicinity of the mountain -- he had yet to appear with YHWH's divine instructions that the Israelites follow a priestly Kenite guide through the wilderness. (For further discussion of these topics, see Julian Morgenstern's "The Oldest Document of the Hexateuch" in H.U.C.A. IV, 1927.) Hathor's son Ihy was both a golden calf and the "Jackal of Light" who could usher the lost pilgrim along to the proper spiritual and temporal pathways. Scolnic is on the right track when he associates the biblical golden calf with the child of Hathor. In his theriomorphic form Ihy would have shared his mother's horned countenance and would have been Hathor's special manifestation, lending a guiding hand to the Prophetess Miriam and her companions in their exodus into Sinai. In order for the "children of Israel" to have best benefitted from Ihy's magical guidance, it is more likely that they would have carried his image with them from Egypt, than to have crafted such a representation of the god in the barren wastes of Sinai. On page 32 of her book Roberts points out the tradition of a divine bull presence among this group before they began their wilderness wanderings. The Israelites' Ihy worship may have ended at the Mountain of YHWH -- as related in the biblical account -- but it certainly did not begin there. The destruction of the golden Ihy calf in the Sinai was a decisive event in the molding of the nation Israel. It may have also marked a turning point in the people's previous relationship with the goddess Hathor. Since Hathor was the mother of both Horus and Ihy, we might say the Egyptians' golden calf and their solar spotted calf were both her offspring and different aspects of the same godly child. Along with her son, Hathor too was rejected at the Mountain of YHWH. If the biblical story of the Israelites at Horeb has any historical basis, it is an account of the people abandoning visible divine images for the invisible God. Dependence upon the invisible, omnipresent divine being is a belief and a worship which reaches past even the monotheistic religion of Pharoah Akhenaten (who may well have been a contemporary of Miriam and the Israelites of the exodus). In one leap of faith the people were called upon to abandon Hathor and Ihy as well as Horus and the Aten -- all images and symbols had to left behind. Once the last image crafted by Aaron had been destroyed and its worshippers purged from their ranks, the followers of Moses could all confess that their god did not dwell in images. The time had come in their journey to leave behind the Celestial Mother and her ancient protection. After Horeb their only covenant was with the Father God. At least that is the symbolic story of the destruction of the Golden Calf at Mount Horeb. It is most unlikely that the Israelite nation abandoned its ties with the ancient gods of the Nile Valley all in a single day. Whatever it was that happened at the Mountain of God, the religion of Hathor lingered on in the Sinai and the Negev for generations thereafter. Hints of the ancient faith show up in the story of the Northern Israelites worshipping a calf image after the division of the Davidic realm back into two lands. To those northern tribes, YHWH was still the young bull-god -- or, at least the invisible YHWH made such an image his earthly foot-stool. When the story of the Golden Calf at Mount Horeb was set down in the Torah, that account borrowed its vocabulary and imagery from the cult of the Northern Kingdom. THE UNIVERSAL GODDESS As Mistress of the Stars Hathor is the nighttime sky: as Mother of the Sun she is the daytime sky. The term "sky," used in this sense, pertains not only to the Earth's atmosphere, but also to the vast reaches of the universe which holds all the heavenly bodies. In this way the Mother Goddess of ancient Egypt may be thought of as being a somewhat akin to Israel's Father God. Like YHWH she was a divininty of the sky, not an "Earth Mother." Hathor, like the demythologized "Father Aten" of Akhenaten's Amarna, was a universal divinity -- she existed and held sway over domains far beyond the Two Kingdoms of the Nile Valley. It is significant that Hathor was not the consort of a male god. She is best understood as the maternal aspect of Divine Being, the total nature of which always transcends physical sexuality. Such a spiritual truth was perhaps beyond the conception of most of those proto-Israelite refugees who so many ages ago departied out of New Kingdom Egypt to find the "promised land." No traditional Egyptian community would have taken such a one-way pilgrimage. Only the most philosophical and mystical devotees of Hathor could have experienced her as so universal a goddess that she might be found in the Palestinian "promised land," as well as in Africa and the Sinai.YHWH was the universal god in a way that Hathor could not quite manage -- he could travel with his worshippers to any place on the face of the earth. In a quaint sort of way Hathor was still bound to bring the solar orb out of Sinai each morning and to take it into the western realm of the dead each evening. Despite her universal aspects she could not abandon her heavenly task and go off wandering with her devotees, appearing as pillars of fire and smoke. The YHWH who entered into human history and accompanied his people on their journeys demanded to be worshipped as a god above all other gods. In the end that kind of exclusivity obscured the feminine nature of Israel's God. Once prophetic Yahwism had evolved into being the actual religion of the masses (and not just the religious idealism of their priests) masculine Mosaic monotheism finally came into its own. After many lapses under the Israelite patriarchs, judges, and kings, Mosiac religion took on its final ethical and devotional evolution among the post-exilic Jews. Judaism occasionally allowed a veiled sliver of God's female face to show: in his glory (shekinah) or in his wisdom (sophia), but there was no place for Hathor hymnists and Ihy followers within its religious ranks -- or in its scriptures either. Miriam the priestess of Hathor had to transform herself into the underling prophetic sister of Moses before she could find a lasting niche among the passages of the Torah. It may now that humankind has progressed far enough along its spiritual spiral to allow the faded memory of ageless Hathor to return -- as the reborn and universal goddess of an emerging communal consciousness. Such a Hathor would not be the consort of Jehovah or the mistress of Allah. And, although she gives birth to the sun and stars, she would hardly be "the Holy Mother of God." Hathor in the twenty-first centiry would be something more like the monotheistic male god, viewed from a new spiritual vantage point. Banned from the solar temples of Akhenaten's Amarna, the Golden One accompanied Miriam and her people into exile in the Sinai -- but she did not emerge with their descendants into the promised land. Her worshippers alomg the Nile called her back into the land of the Two Kingdoms -- Akhenaten's successors had sense enough to rebuild her temples and welcome her back. After more than 3000 years, perhaps the time has come for the rest of humanity to embrace her return as well.  Text by Dale R. Broadhurst. Graphics adapted to illustrate the essay |

return to top of page

The Sistrum in the Sinai | Hathor Home Page | Dale R. Broadhurst Home Page

last updated: Feb. 1, 2006