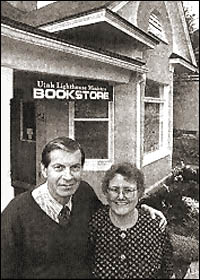

I PLACED earlier versions of this review on-line in 1999 and early 2000, but, in each case, I was dissatisfied with the content and ineffectiveness of those presentations. After mulling the idea over for several months, I became determined to speak directly with Mr. and Mrs. Tanner before I finalized the format and essential content of this review. In October 2000 I traveled to Salt Lake City and met with the Tanners at their house, hoping to discuss with them ideas and events relative to the Solomon Spalding authorship claims for the Book of Mormon. As it turned out, both my time and Mr. Tanner's stamina were too limited for me to delve very deeply into this complex subject. I did not get around to speaking with them specifically about their 1989 article on William H. Whitsitt, but I came away from that short encounter, renewed in my original resolve to rewrite my review. There is good reason for my presenting the conclusions which follow, in as clear and unambigious language as I can possibly articulate. During the decade and a half that has passed since the Tanners published their 1989 article, it has become increasingly obvious to several informed readers and critics that their article demonstrates both shoddy scholarship and an unwillingness on the part of the Tanners to set aright some unconscionable journalistic mischief -- reckless wrongdoing of their own creation. With this thought in mind, I updated the following review at the beginning of 2002, supplemented it with additional links a year later, and now place the results on-line for the consideration and use of other students of Mormonism.

A Matter of Identity

There appears to be no escaping the inherent problems of personality when a critic like myself examines and reports upon such an enigmatic and engaging subject as "Mormonism." From its inception the "restoration movement" has based itself upon subjective personal experiences and expressed itself, to a large degree, in subjective personal testimonies. The merging of all these personal feelings and realizations, into a single community, naturally creates a somewhat strange and inward-looking group of "peculiar people." A flip-side to this comfortable, latter day Laputa is found in collections of frequently harsh and hostile "anti-Mormon" testimonies -- in multitudes of voices decrying the alleged "delusions" of the Saints and their religion. Personal testimonies call for personal identification and there has been no scarcity of these self-proclaiming soliloquies throughout all the years between us and 1830. I draw some small consolation in being a member of a restorationist "faith community" that has been evolving out of (and away from) traditional "Mormonism" for many decades and which now appears ready to trade the title of "Latter Day Saint" for "Communicant of Christ." I try to find some complementary optimism in the occasional pleas voiced by LDS leaders, attempting to disassociate themselves from the old terms, "Mormon" and "Mormonism." Still, traditional Mormonism seems unlikely to disappear from our world; as quickly as one person leaves it, several others embrace it. Also, I cannot ignore the fact that this religion and its adherents have permanently shaped my personality and identity. In much the same way, the well-known "anti-Mormon" Tanners are a product of Latter Day Saintism. I am uncomfortably aware, that to many onlookers, the Tanners and I must appear to be nothing more than opposite sides of the same coin. With this humbling realization well in mind, I do not feel too culpable in offering my admittedly personal opinions regarding one specimen of their research and reporting.

When I first launched the Spalding Studies Home Page, in the spring of 1998, it was placed on-line accompanied by my express hope that it might provide an internet-based forum where interested persons might "initiate and assist studies" reviewing the career and works of the Rev. Solomon Spalding. I had hoped that the site's visitors might eventually develop enough interest in that forgotten writer and his writings to promote a scholarly interchange, more or less apart from our consideration of contemporary Mormonism. I still hold onto that hope as a sort of ideal, but I've since resigned myself to now and then stepping into the gritty arena of pro-Mormon and anti-Mormon contentions -- where subjective arguments and personalized apologetics flourish with barely a blush of shame. This particular arena encloses a playing field where contention among individual personalities appears to be unavoidable. It is also, sadly, an arena where the players and spectators have grown accustomed to attacking the announcers and referees when they do not like the outcome of the struggle. And, as in ancient times, the messenger who brings unpleasant news (no matter that it may be true and important news) risks bearing the brunt of peoples' anger and retribution.

In another web-posting I've made reference to the overheard remark, that Jerald and Sandra Tanner might well have been put on the payroll of the LDS Church, in consequence of their inadvertent (?) journalistic contributions to the cause of that organization. At one point I was considering writing them an apology for publicizing that sentiment; but then an old copy of their Salt Lake City Messenger for October of 1989 (issue no. 73) arrived in the mail from Utah Lighthouse Ministries. In that publication I read their article, "Mormon And Anti-Mormon Forgeries" and immediately felt any inclination for my apologizing evaporate. After carefully perusing this 1989 example of Tannerite "scholarship, I am more convinced than ever that its authors effectively function, in some important instances, as apologetic surrogates for the LDS Church. In saying this I am not necessarily criticizing the motivation and methods of persons in positions of trust within the LDS hierarchy, nor am I disparaging the generally valuable contributions made over the years by Jerald and Sandra Tanner. I am simply stating what appears to me to be the clear fact, that regardless of their publicized squabbles with Intellectual Reserve and similar contentions spanning many years, that the Salt Lake City couple persistently support certain tenets relating to Mormon origins and evolution, the effect of which is mutually beneficial to themselves and to the Church.

The Tanners' 1989 Conjectures

At first glance, to some readers, this couple's 1989 Messenger article might appear to be nothing more than a laudable exposition on the subject of "forgery" among the Mormons, ex-Mormons, etc. This is indeed a matter worthy of a good deal of careful investigation and elucidation, but such commendable investigative reporting is not what the Tanners have provided in their poorly titled 1989 article.

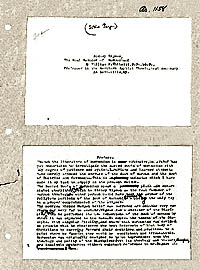

Their 1989 compilation might better be called "We Accuse the Rev. William H. Whitsitt of Forging the Spurious Cowdery Documents." In short, the researchers consider the origins of two long-disputed documents: (1. Defence in a Rehearsal of My Grounds for Separating Myself From the Latter Day Saints (a pamphlet attributed by some to Oliver Cowdery); and, (2. the so-called "Overstreet Confession" (a written document attributed by some to a writer who impersonated Oliver Cowdery). Having informed their readers how they determined that these obviously anti-Mormon concoctions "are forgeries" written during the early 1900s, the Tanners present "three theories with regard to the authorship" of the spurious documents.

The Tanners nowhere say to their readers that the speculation they propound in their article is confirmed or corroborated by even a single reputable specialist in the discipline of historic documents relating to Mormonism -- they simply say they "feel" that one of the following alternatives must be true: (1. "that the documents were forged by R. B. Neal," (2. "that they were forged by William H. Whitsitt," or, (3. "that the documents were forged by an unknown person who had access to" the Whitsitt manuscript biography of Sidney Rigdon (held by the Library of Congress since 1912), the anti-Mormon "writings of R. B. Neal" and "all of the other writings necessary to commit the forgeries."

In their 1989 article the Tanners offer this conclusion: "Now, if Cowdery's Defence had been available in 1885, Whitsitt certainly would have cited it to prove his position that Rigdon impersonated the angel. In any case, this parallel between the Whitsitt manuscript and the Defence is remarkable and certainly raises the question as to whether Whitsitt's idea was incorporated into the Defence." The Tanners have coupled their superficial, subjective examination of these matters with an over-active imagination (see their section, "New Evidence On Forgeries," and those article sections following) to deduce three inter-related possibilities, all of which depend upon someone having mischievously applied unique (?) assertions set down by the Rev. Dr. William H. Whitsitt (1841-1911), the third President of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary at Louisville, Kentucky, in an 1885 manuscript. But, as a matter of fact, the "angelic" assertions of Dr. Whitsitt are in no way unique. The Tanners suppress the fact that numerous early writers guessed that Sidney Rigdon acted as Smith's "angel." They also pick 1885 as representing the latest date when Whitsitt might have taken notice of other writers' claims linking Sidney Rigdon to Smith's "angel." Actually, William H. Whitsitt could have quoted these sources, if he had cared to, as late as 1891, when a summary of his views on the subject was published in a widely-read reference book. Whitsitt did not bother to cite contemporary sources or earlier sources on this self-evident point, but that oversight does not mean that he was the first investigator of early Mormonism to reach such conclusions. The Cowdery "Defence" surfaced in mid 1905, by which time Whitsitt was a tired old man who no longer bothered to update his writings concerning Rigdon, Mormon angels, etc. So, even if a copy of the Cowdery "Defence" had reached him, before his death in 1911, it is doubtful that he would have taken the trouble to add a notice of it to his unpublished, abandoned Rigdon biography.

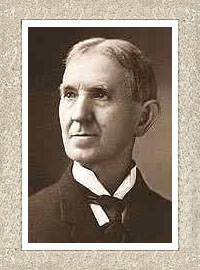

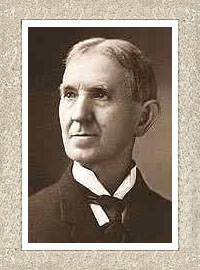

William H. Whitsitt (1841-1911)

The Tanners' Tactics

Before I take a look at some of the bits and pieces which constitute or seemingly support the Tanners' 1989 theories, I'd like to point out one very important effect of their conclusion. By painting Dr. Whitsitt as a plausible anti-Mormon forger (or as an apparently blithe accessory to the act of anti-Mormon forgery) they implicitly call into question the validity of anything this noted professor of church history ever wrote concerning Mormonism, its leaders, its scriptures, or its early history. It doesn't matter at this point that they've told their reading jury to "disregard that last remark," until the remainder evidence has been presented in their case. All of their reader-jurors, at this point, already have the notion well planted in their minds that Whitsitt was a likely liar, out to destroy Mormonism by any means available. This insidious impression is foisted upon the readers before they ever reach the meat (?) of the Tanners' 1989 article. There are various journalistic stratagems which can be used to influence readers' opinions before they ever see supportive evidence, but this Tannerite ploy is one of the shoddiest attempts at prejudicing folks' opinions I've ever seen. The partisan indoctrination the Tanners impart to their readers in this particular case would be perfectly at home among the pages of infamous 1839 issues of the Elders' Journal! What are we to make of this piece of work?

First of all, by their repeatedly calling Whitsitt's honesty into question the Tanners (unwittingly?) provide pro-Mormon polemicists with sufficient ammunition to preemptively shoot down any one of Whitsitt's various assertions regarding the 19th century origin and literary structure of the Book of Mormon. After all, if your antagonist is a suspected liar and forger, why should you even bother listen to that person and his or her assertions regarding the origin and early evolution of the Latter Day Saint movement? The troubling questions of uninformed LDS members, who may have heard something about Dr. Whitsitt's assertions, can be immediately put to rest, simply asking some

qualified Church employee to compile a reassuring, Nibleyesque article for The Ensign. Somewhere in that article, the writer can insert a citation or an allusion to the Tanners' calling Whitsitt's veracity into question. That reference alone (made even in a fine-print footnote) will be enough to put to rest the embarrassing questions of practically any Mormon, as to the veracity of Dr. Whitsitt. After all, if "even the Tanners" say he was of questionable character, then the issue is already settled, to his eternal discredit.

"Shooting the Messenger"

Throughout human experience it has always been easier for us to shoot the messenger than it has been for us to hear, consider, and respond to a troubling message. When we are in denial of our problems, somebody must be to blame, other than ourselves, right? And, as the Tanners astutely point out, "it would probably be very difficult for anyone to disprove the accusation" against Whitsitt's honesty. If we do not like his message -- saying who the "angel" was, etc. -- then we can simply dispose of this disturbing messenger. As I read and re-read the second half of the Tanners' article, I cannot help but recall the many examples of journalistic character assassination I've seen in early Mormon publications. Have these modern writers knowingly carried on the disreputable traditions of their forefathers? When we cannot score valid points against an opponent in a debate, by presenting solid, counter-arguments, practically the only way left for us to win the debate is to trick that opponent into attempting to disprove the negative. And, as we all know, when a person tries to refute negative accusations about his or her honesty, the task is a daunting one -- simply standing up and saying "I am not a crook!" works no better for common beings than it has in the past for U. S, Presidents. So, it is obviously not too difficult for any of us to end a debate, before it ever begins, simply by questioning the integrity of our opponent.

Accomplishing even this little, we may walk away as the seeming winner of any dispute. That appears to have been the Tanners' first tactic in dealing with Whitsitt.

Using Spalding as the "Straw Man"

Secondly, the Tanners shore up their own rejection of an ill-defined straw-man they call "the Spalding theory" by painting Whitsitt as "a very strong believer in the Spalding theory concerning the origin of the Book of Mormon." In their minds the primary purpose behind the early 20th century forgery of the two spurious anti-Mormon documents was to seemingly reinforce this so-called "Spalding theory," and thus to vilify and perhaps even overthrow the Latter Day Saint religion.

If the Tanners prejudiced opinion of Whitsitt's primary motivation were correct, and if he promoted the Spalding theory "tenaciously," then Dr. Whitsitt must have obviously followed a misguided and self-serving agenda from the very beginning -- or so it might seem to the Tanners' readers. The Tanners imply, that if such a "tenacious" zealot in the cause of the "Spalding theory" wrote anything disputing their own views regarding Mormon origins, that his obvious prejudice must disqualify his accusations from any reader's serious attention. Also, the Tanners' marking Whitsitt as "tenaciously" fighting for the "Spalding theory," automatically discredits the man's scholarship in the eyes of practically all traditionally "faithful" Latter Day Saints. It hardly needs to be pointed out that in their writing and publishing all of this, the Tanners clearly display their concurrence with the LDS "party line" on the inadmissibility of any historical evidence supporting the Spalding authorship claims.

Ignoring the Problematic Sidney Rigdon

Thirdly, by focusing their readers' attention primarily upon the matter of forgeries relating to one of the Three Witnesses to the allegedly divine origin of the Book of Mormon, the Tanners avoid engaging the weightier implications of Rigdon possibly having actually been "the Messenger" to Joseph Smith, Jr., the "Restorer" of the Aaronic priesthood to him and Cowdery, the "Angel of the Prairies" to Parley P. Pratt, and the "Shining Seraph" to Eliza Snow. While they selectively acknowledge these kinds of allegations concerning Rigdon's role in the earliest stages of Mormonism, the Tanners also carefully avoid making any useful inquiry into the possible veracity of such old assertions. The grounds and parameters they have established for admitting evidence into the bounds of their 1989 article disallow their readers viewing the content of those old assertions from any perspective other than the Tanners' own viewpoint. This sort of ploy is not unusual on either side of the Mormon/anti-Mormon fence, but it hardly allows for objective scholarship. Rather, the Tanners marshal Whitsitt's adverse opinions on tangential matters, in order to further their own, highly subjective, prejudices concerning the anti-Mormon forgeries of 100 years ago.

The Tanners' intentional rejection of any possible pre-baptismal role for Rigdon in the unfolding of Mormon origins (prior to October 1830) is a matter seemingly separate from their equally studied inattention to any substantial Spalding authorship claims. However, in this case, they have subtly interwoven their two negative viewpoints on these historical questions into a single key presupposition -- a prejudicial assumption that serves only to help pull the questioning reader and hopeful investigator into an unproductive, closed-minded "Tannerism," thus thwarting our proactive inquiry into the most important questions relating to Mormon origins. The Tanners apparently expect their readers to generally ignore the problematic Rigdon, along with his personal brand of radicalized, pre-millennial Campbellite doctrines and practices (mostly unique doctrines and practices, I might add), many of which are also neatly spread throughout a certain book first published in Palmyra in 1830. For more elucidation on this topic, see the excusus contained in my review of Dr. Terryl L. Givens' 2002 book, By the Hand of Mormon.

Dale R. Broadhurst

Where This Reviewer is Coming From

Having already taken the trouble to address the Tanners' article within the context of personal experience impacted generally by Mormonism and anti-Mormonism, I'll next extend the scope of my review to include a few disclosures of my personal views. In other words, for a few paragraphs I'll allow myself the same subjectivity the Tanners apparently methodically allow themselves in carrying out their peculiar work. Following that, I'll attempt to muster enough objectivity to critically address a few specific points raised by the Tanners in their 1989 article.

For most of my past twenty-five years' research and reporting in Mormon studies, I have not typically tried to inject my personality and personal agenda into my labors. Indeed, the practicalities of my generally anonymous research and unrestrained sharing of information have always taken precedence over any vagaries expressed in my infrequent and intentionally unpublished reporting. This way of doing things no doubt evolved on my part as a prudent consequence of the influence of my role models and mentors within the RLDS Church. I have viewed my most productive contributions to scholarship and friendship as falling within the limits of information-provider and enabler for other researchers and writers. With the advent of web-based self-publishing, however, I find myself in the unaccustomed and uncomfortable role of being an on-line journalist and digital media innovator -- and this after having long since discarded the bulk and accessibility of my favorite research resources and relocating to the far off Pacific, where Mormonism and Latter Day Saintism are but minor accessories of the relentless expansion westward of things American.

Nevertheless, with my 1998 resumption of work on the Spalding Research Project and my subsequent launching of The Spalding Studies Home Page and other web-sites devoted to the study of early Mormonism, I have slowly and reluctantly adopted the medium of web-casting to better share my work and discoveries. Self-publication in this medium regularly entails the discarding of traditional scholarly journalism's various restraints and helps. The rapidity of a two-way flow of electronic communication brings in its wake a potential flood of personalized feed-back. In my case, this is something I experience as a mixed blessing at best. It has become a daily experience for me to receive and read numerous e-mail messages informing me that my on-line presentations are in opposition to the "truth," because I have provided information and analysis on Solomon Spalding, Sidney Rigdon, etc. which does not conform to traditional, "faith-promoting" convictions typical to the Latter Day Saints. At the same time, I also find myself informed by other unsolicited messages that I must be deluded cultist for retaining my membership in restorationist faith community, the press of which continues to churn out copies of the Book of Mormon. Finally, several of those students of religion and history with whom I share a good deal of common intellectual ground continue to tell me that Fawn M. Brodie, the Tanners, and other "experts" on Mormonism have long since exploded the Spalding authorship claims, along with the possibility of Rigdon's having been at all involved in the origin of that religion.

It is from this less than popular starting point that I've begun to address issues relative to the Latter Day Saint experience, such as Tannerism. "Tannerism" I define as: the process whereby one presents the appearance of offering substantial explanations for Mormon beginnings and problematic actions, while at the same time consciously avoiding useful new inquiry into the most relevant aspects of those origins and actions. Such pseudo-responsiveness to such important matters, of course cannot prevail forever. When unavoidably faced with the difficulties intrinsic to responding in a material manner to the explicit assertions of a William H. Whitsitt, or the insightful web-casting of a Ted Chandler, the more intelligent and responsible proponents of Tannerism will eventually find themselves significantly changed by that encounter, no matter whether they manage to prevail in a few of the inevitable contests or not. This change need not necessarily involve the personalities of Jerald and Sandra Tanner, as they will disappear from the scene sooner or later, leaving Tannerism entrusted to the care and continuation of other anti-Mormons. But be that as it may, change in this mirror-image manifestation of Mormonism will almost certainly be healthy in the long run and I have no apologies to offer in working as an agent to help spark its further and better evolution. For without such timely and vigorous evolution, Tannerism will sooner or later be co-opted and put to use in the self-interest of the larger, more flexible, less "Mormon" LDS Church of the near future. The voices of warning against incipient theocracy have grown faint in these days of accommodation of and disinterest in established hierarchical religion. As for myself, it does not really matter whether my personal hobbies in history and religion turn out to be of much value or not. What will matter is the coming evolution in the process by which understandings such as my own are communicated and considered by those who are in positions to change things for the better. So, here I stand, armed with little else than a engaging web persona and a passion for productive inquiry -- I can do naught else.

The Rev. Sidney Rigdon

(computerized enhancement)

Sidney Rigdon as John the Baptist

and Smith's Angelic Messenger

It must be admitted, purely as an academic possibility) that the Tanners may be correct in theorizing that Dr. Whitsitt stooped to the deceitful act of forging anti-Mormon documents. It is equally correct to say that, given the current dearth of useful information in this case, it would be difficult to prove that he did not. To tell the truth, I am not particularly fond of finding myself defending the distinction of this particular southern gentlemen. He was, to a certain extent, a prejudiced opponent of my chosen faith and of my ancestors in that faith. Dr. Whitsitt placed both Campbellism and Mormonism within the outer bounds of variant Christianity, but he could find nothing redeeming about the Mormon experience. Whitsitt obviously detested both Alexander Campbell and Sidney Rigdon to the point of utter contempt. However, that being admitted, there is no known reason for anyone to accuse Dr. Whitsitt of being anything other than an honest and honorable man, noted for gaining one personally costly scholarly victory in his courageously defending the more tenable side in a doctrinal dispute of great importance among Southern Baptists. The truth of his side in that seminal religious struggle was not positively affirmed until years after his death, however. In the midst of that divisive debate Whitsitt summoned the personal courage and wisdom to enable him to step down from a position of power and prestige among the Southern Baptists. He made this injurious personal sacrifice in order to help calm the stormy ecclesiastical waters which were then swirling around him and his seminary. His actions in that struggle speak volumes about his integrity and devotion to the Christian cause.

William H. Whitsitt, the fiercely independent thinker and pious former Confederate chaplain did not consider any heavy-handed attempt at converting people to his own views justifiable, even when he knew he was right and his opponents were wrong. It is almost impossible for me to picture this kind of a man resorting to nefarious forgery in a Quixotic contest with the Mormons, so late in life, when his thoughts were more likely centered on meeting his Maker than on struggling to win denominational causes.

The Tanners are blatantly in error in their charging that Whitsitt was a "tenacious" supporter of the Spalding "theory" (whatever that theory might consist of in their own minds). Whitsitt, in his manuscript biography of Sidney Rigdon, several times makes it quite clear that he had no passion for all the seedy twists and turns this authorship explanation had taken by the time it came under his scrutiny during the early 1880s. Whitsitt also made it clear that he harbored even less regard for the broken down, former Congregational evangelist from Connecticut who allegedly wrote the original of the Book of Mormon. As Whitsitt says, if he could have avoided reporting the Spalding portion of the Spalding-Rigdon authorship explanation, he certainly would have. Dr. Whitsitt points out in the pages of his Rigdon biography. that he could have built just as strong a case for his primary thesis -- that the Rev. Sidney Rigdon originated Mormonism from his own radical, millenarian Campbellism -- without resorting to any use of the Spalding authorship claims whatever. He included reference to those claims, first of all, because no biographer of Rigdon can honestly exclude some mention of them from his biography. Dr. Whitsitt took the trouble to develop certain aspects of the Spalding authorship rationale because he realized that a person like Rigdon would have more likely edited an existing preudo-historical narrative than he would have concocted such a document from scratch.

Whatever the Tanners might have to say about Spalding, Rigdon, etc., it seems to me to be a foregone conclusion that a "printer's manuscript" of one of Solomon Spalding's works of fiction was retained in a Pittsburgh print shop until the early 1820s and that, through his association with printers like Silas Engles and Jonathan Harrison Lambdin, the young "journey man tanner," Sidney Rigdon eventually acquired access to that pseudo-historical oddity. Whether this segment of the historical reconstruction is fully true, only partly true, or a total mistake, matters little to Whitsitt's expression of his central thesis in Rigdon's biography. The Tanners do not see things this way, however. By concentrating only upon Whitsitt's critical use of certain Spalding authorship elements in his writing the Rigdon biography, the Tanners manage to both ignore the professor's core message and simultaneously to consign him to the ranks of unenlightened dupes accepting the Spalding "theory."

A Search for Some Important Answers

The Tanners pretend to a great discovery, in their assigning to Dr. William H. Whitsitt the genesis of the idea that Sidney Rigdon could have been the alleged angelic messenger and heavenly baptismal restorer spoken of so reverently by Joseph Smith, Jr. Whether the Tanners are correct in assigning to Whitsitt the origin of the Rigdon as the angel-baptizer idea is an interesting question. But it is a question best answered through diligent research among primary historical sources rather than by a Tannerite epiphany, striking the untutored mental wanderings of Jerald and Sandra Tanner as they ponder the Whitsitt transcripts Byron Marchant and I have assmebled for their inspection.

The place to start looking for an answer is in the 1833 Book of Commandments. There, in the opening verses (1-7) of Chapter XXXVII: "A Revelation to Joseph, and Sidney, given in Fayette, New York, December, 1830," we read:

Listen to the voice of the Lord your God, even Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end, whose course is one eternal round, the same today as yesterday and forever. I am Jesus Christ, the, Son of God, who was crucified for the sins of the world, even as many as will believe on my name, that they may become the sons of God, even one in me as I am in the Father, as the Father is one in me, that we may be one:

Behold, verily, verily I say unto you my servant Sidney, I have looked upon thee and thy works. I have heard thy prayers and have prepared thee for a greater work. Thou art blessed for thou shalt do great things. Behold thou wast sent forth, even as John, to prepare the way before me, and before Elijah which should come, and thou knew it not.

Thou didst baptize by water unto repentance, but they received not the Holy Ghost; but now I give unto thee a commandment, that thou shalt baptize by water, and they shall receive the Holy Ghost by the laying on of hands, even as the apostles of old... [emphasis added]

Mormon scriptural commentators, apologists, and historians alike have generally spoken of this revelation being a divine identification of the radical Campbellite, Sidney Rigdon, with John the Baptist. F. Mark McKiernan went so far as to entitle his slender 1971

Sidney Rigdon biography, The Voice of One Crying in the Wilderness... While it is marginally possible that some of the post-1905 writers on Rigdon have derived some of their Rigdon=John the Baptist imagery from the bogus Cowdery Defence (and thus, according to the Tanners, from Whitsitt), this would not be the case for earlier publications wherein Sidney Rigdon is compared or connected with John the Baptist. Rigdon's identification as being a great proselytizer and baptizer for the Campbellites goes back at least to 1827, if not before. It was a distinguishing mark of the Campbellite ministers of those times that they were willing baptize a new convert almost immediately following his or her expression of belief in the "primitive gospel." Rigdon's reputation as a great baptizer naturally carried over into early Mormonism, where baptism was also performed immediately after a profession of belief and repentance on the part of new converts. Already raised to the dignity of the preeminent divine ordinance by the Campbellites, baptism among the Mormons became the only ordinance worthy of being called "sacrament." Clearly the identification of Rigdon as a great baptizer -- like John in the Bible -- and the coupling Rigdon's name with John's name, was a notion firmly implanted in Mormon minds as early as the end of 1830.

1867 Depiction of Smith & Angel

Smith's Angels - Divine or Human?

When the first Mormon missionaries went out from Palmyra to peddle the newly published Book of Mormon and beat the bushes for converts, they took with them the story of Joseph Smith's angelic visitations. But the earliest public reaction to "Joe Smith's Angel" was not always very sympathetic and incredulous writers often demoted the Mormon "angels" to a lesser and very human status.

The June 12, 1830 issue of the Palmyra Reflector told how the local boy-seer's stories of a treasure-guarding ghost had evolved into angelic visitations:

"Now the rest of the acts of the magician, how his mantle fell upon the prophet Jo. Smith Jun. and how Jo. made a league with the spirit, who afterwards turned out to be an angel, and how he obtained the "Gold Bible." Spectacles, and breast plate..." The issue of Feb. 28, 1831 adds: "It is well known that Jo Smith never pretended to have any communion with angels, until a long period after the pretended finding of his book..."

A few months later the first Mormon missionaries had reached northern Ohio, where some people greeted them as heaven-sent messengers of a new revelation. This identification of Mormon elders Cowdery, Pratt, etc., was perhaps easiest for the local Campbellites, who had accepted Alexander Campbell's redefinition of "angel" as "messenger" in his translating passages of the Bible's Greek into colloquial English. Just as celestial angels were "messengers" and "fellow servants" with Cowdery and Pratt, so also were they and other LDS missionaries "messengers" and "fellow servants" with the angels of the new dispensation. According to Ezra Booth's 1831 account, having himself just converted to Mormonism, the Rev. Sidney Rigdon observed of Oliver Cowdery, that "his heart open, and it was as pure as an angel," and that the messenger from Palmyra had brought "a testimony from God."

The editor of a local paper, the Hudson Observer, was less credulous concerning Cowdery's role as a messenger of divine tidings: In his issue of Nov. 18, 1830 he wrote: "For several days past, four individuals, said to have formerly resided in the State of New-York, have appeared in the northern part of Geauga County, assuming the appellation of Disciples, Prophets, and Angels. Some among us, however, are led to believe that they are nothing more than men, and impostors..."

Compare those reports to the following account from the Mar. 1, 1831 issue of the Cleveland Advertiser: "Some months since, a young lawyer living in the western part of the state of New York... wrote the wonderful Mormon bible... he marvellously appeared in disguise, in the form of an angel, to a man named Smith, and revealed to him where he would find the sacred treasure..." The same newspaper, only a few days earlier had announced Sidney Rigdon was the person who concocted Smith's wonderful Mormon bible: "Rigdon was formerly a disciple of Campbell's... but... to operate on his own capital... wrote, as it is believed the Book of Mormon."

So, as early as the first weeks of 1831, accounts in the popular press provided sufficient information for people to demote the Mormon "angels" to human status; to identify the "angel" who provided Smith with his "wonderful Mormon bible" as being a mere man; and to identify the writer of the book as none other than Sidney Rigdon. As the Mormons settled in at Kirtland and began baptizing new converts in that region, the same popular press published accounts of angelic visitors attending those night-time baptisms, walking silently near the awe-struck converts and strengthening their faith in the new revelation. In some accounts the silent reputed angel was said to be none other than Smith himself, operating surreptitiously and in disguise. Certainly the judicious application of a little phosphorus to the person of a Mormon leader like Smith or Rigdon could have easily produced such faith-promoting results. Elder James J. Strang demonstrated a rather similar heavenly "miracle" to his followers during the late 1840s. Back in 1831 all the necessary elements were in place for anybody with a little common sense to have identified Sidney Rigdon as one of the Mormon "angels" and, more specifically, as the very messenger who supposedly brought Smith his "wonderful Mormon bible." This logical identification of Sidney Rigdon with Smith's "angel," in the minds of incredulous non-Mormons, did not have to wait sixty years, until William H. Whitsitt saw a summary of his Rigdon studies published in 1891 -- this was an incipient impression in some peoples' minds, beginning in the earliest days of Mormonism.

Rigdon as a Fake Divine Mesenger

Eber D. Howe printed the 1830 Mormon "revelation" to Rigdon on pages 107-109 of his 1834 Mormonism Unvailed. The editor of that book follows his quotation of the 1830 "revelation" to Rigdon, by saying: "We before, had Moses and Aaron in the persons of Smith and Cowdery, and we now have John the Baptist, in the person of Sidney Rigdon." According to the Rev. Clark Braden, a good deal of the information in Howe's book was supplied by the Disciples of Christ leader in Mentor, Matthew S. Clapp. The account of Rigdon in Howe's book is largely taken from Clapp's earlier article, published in Howe's newspaper on Feb. 15, 1831. In Clapp's earlier report he says that the Mormon missionaries to the Lamanites who converted Rigdon in 1830, "applied to O. Cowdery prophetical declarations which are directly and particularly applied to John the Baptist, harbinger of the Messiah." But by 1834 (when Clapp's report was rewritten for Howe's book) it was obvious to most observers that Cowdery's star had set, while Sidney Rigdon's "John the Baptist" role had made him the second most important leader in the Mormon movement.

Previous to his associating Sidney Rigdon with John the Baptist, the editor of Howe's book had already said: "We may here stop to remark that an opinion has prevailed, to a considerable extent, that Rigdon has been the Iago, the prime mover, of the whole conspiracy" (page 101). So, in the very first anti-Mormon book, the reader finds Rigdon identified as the Mormons' "John the Baptist" and also named as the originator "of the whole conspiracy." It takes only a small step in logic for any reader of these lines to accept the logical deduction that Sidney Rigdon played the part of John the Baptist in the purported May 15, 1829 "restoration" of the Aaronic priesthood to Joseph and Oliver. Documentation of a month and a half gap at this point in Rigdon's Ohio chronology was given by RLDS Elder Edmund L. Kelley in 1891 and reprinted in the widely-read Saints' Herald in 1894. Not only could Rigdon have been with Joseph and Oliver at the time of the priesthood "restoration," any reader of the Saints' Herald or Zion's Ensign (which reprinted the chronology) could have come to the very same conclusion as early as 1894. The logical identification of Sidney Rigdon as Smith's divine messenger, in the minds of incredulous non-Mormons, was not a conclusion that could have only been made by William H. Whitsitt. And, for the same reasons, it was not a conclusion that could have only been made by somebody of had read Whitsitt's unpublished biography of Elder Sidney Rigdon.

By 1830 Sidney Rigdon had long thought of himself as being, as much as was then possible, a doctrinally pure Baptist -- one of three Campbellite reformers (the others were Rev. Walter Scott and Rev. Adamson Bentley) who stood ready to baptize repenting new believers at a moment's notice and who was yearning to "restore" the laying on of hands for the reception of the Holy Ghost as the culminating ordinance in baptizing adult converts by immersion for the remission of sins. Of course Sidney could not claim the divinely authorized power to administer this pure and complete baptism until he himself had received baptism and ordination at the hands of a fully authorized latter day elder. This was a key point in Rigdon's religious evolution and it should not be lost sight of. Rev. Sidney Rigdon, as he ministered among the Campbellites at the close of the 1820s, could not claim the culminating heavenly authority he desired, until he was baptized, confirmed and ordained by a divinely authorized person, and no such person was to be found among the Campbellites. Rigdon could either receive his desired authority from the hands of an angel (he and Smith later inserted such angelic ordinations into their improvement of the Bible) or from the hands of a divinely appointed fellow human being.

So, from whom did he receive these enabling ordinances in 1830? Rigdon's "restored" priestly powers came under the hands of Elder Oliver Cowdery, who, in turn, reportedly received his priesthood authority directly from the divine messenger, John the Baptist -- who was a celestialized being, like Moroni the son of Mormon; or, in other words, an "angel." Here is just one of the many intriguing connections between Sidney Rigdon and the famous baptizing prophet of the former day saints. Whether the celestialized John came to empower Smith and Cowdery, carrying his head under his arm, like a bloody Cumorah treasure-spirit, history does not recall. But, if some early writers are correct, the latter day John spelled his name S-i-d-n-e-y, and acted out a part rather like the fellow in the old song, who was his "own grandpa." If "Rigdon the Baptist" imparted priestly authority to Oliver, and Oliver then imparted that same authority to Rev. Rigdon of Mentor, Ohio, then the latter must have received his baptism and priesthood, "by hook or by crook." This is exactly the sort of historical irony that captured the attention of Dr. Whitsitt, and it is exactly the sort of historical discovery the Tanners seek to conceal, by their dragging Whitsitt's good name and reputation through the mud.

Sidney no doubt delighted in his identification with John the Baptist, either as the unknowing fore-runner and eventual herald of Joseph Smith, or (more likely) as the Mormon herald of the coming millennial reign of Christ. Smith's revelation to Sidney allowed for either outcome -- just so long as Sidney "knew it not." Stepping deftly into the sandals of this ancient "voice of one crying" repentance "in the wilderness," Sidney was not above invoking his first century alter-ego in rebuking the editor of the Millennial Harbinger, his former Campbellite mentor, Alexander Campbell: "When John the Baptist came as the harbinger of the Savior, in six months after, he could say, (John 1:29) Behold the Lamb of God who taketh away the sin of the world. But the poor [Millennial] Harbinger, like a widowed dove, can find no mate. It has been five years abroad on the earth, and going up and down on it, but no Millennium yet; not able to point to the place where it, or any part of it is to be found. Let the Editor of the Harbinger be silent about impositions till he corrects his own, and ceases to practice fraud himself." (Sidney Rigdon, "The Millennium II," Evening and Morning Star, Jan. 1834 pp. 126-27.)

Pomeroy Tucker Tells His "Messenger" Story

Skipping over three decades (in which there are very likely numerous published identifications of Rigdon as John the Baptist, and/or Smith's angelic messenger) we come to the writings of Pomeroy Tucker. Mr. Tucker was once the editor of the Wayne Sentinel in Palmyra and he had more than a passing acquaintance with Joseph Smith, Jr. As early as the year 1858 Tucker published an account crediting the writing of the Book of Mormon to Sidney Rigdon, who he said "furnished the literary contributions" to for Smith's 1830 book, and who "was the first 'messenger appointed of God.'" As I've already said, the technical term "messenger," as Tucker uses it herem is an important one. Rigdon matured his religious thought under the tutelage of Alexander Campbell, who insisted on exact translations of scriptural terms from the Greek: for Campbellites "baptism" was "immersion" and "angels" were "messengers". For Sidney Rigdon, speaking during the winter of 1830-31, the terms "preacher," "fellow servant," "messenger," and "divine messenger" would have been closely interrelated, and perhaps (in the case of his own role among the Mormons) one in the same. According to Orson Pratt, the young Joseph Smith was "filled with the most ernest desire, 'to commune with some kind of messenger who could communicate to him the desired information of his acceptance with God.'" Elder Pratt does not say whether a "messenger" sent in the form of an ex-Baptist preacher from Mentor, Ohio would have filled this bill, but an 1831 newspaper report on the Mormons says: "Ringdon [sic] partly uniting with them [Smith and associates]... by the suggestions of the Ex-Preacher from Ohio, [Smith and associates] thought of turning their digging concern into a religious plot... They began also to talk very seriously, to quote scripture, to read the bible, to be contemplative, and to assume that grave studied character, which so easily imposes on ignorant and superstitious people... At last a printer in Palmyra undertook to print the manuscript of Joe Smith... They were called translaters, but in fact and in truth they are believed to be the work of the Ex-Preacher from Ohio, who stood in the background and put forward Joe to father the new bible and the new faith."

In his recollections of the Palmyra of forty years past, Pomery Tucker gives much the same report as was published in the 1831 article, just quoted. Tucker fills in details only broadly sketched out in that article, however; most importantly he speaks of a "mysterious stranger" who twice met with Joseph Smith between 1827 and 1830 (Origin and Progress of Mormonism, NY, D. Appleton & Co. 1867, pp. 28, 46, 75-76, & 121.)

Perhaps Tucker's reminiscence at this point relies upon the same wellspring of testimony from which Palmyra residents drew to provide information for the 1831 account of early New York Mormonism, the Joseph Smith, Sr. family, and the mysterious ex-preacher from Ohio who brought them the text for the Book of Mormon. Then again, Tucker may have had access to old Palmyra information as obscure as that which gave rise to Lucy Mack Smith's tale of a mysterious "stranger" miraculously assisting her son at the time he was doing his "translating" (Biographical Sketches of Joseph Smith the Prophet... Liverpool, 1853, p. 119) or to the much later statements of alleged eye-witnesses like Abel Chase and Lorenzo Saunders, telling how they had encountered Sidney Rigdon near Palmyra months before his baptism as a Mormon. At any rate, we read in Tucker's comments one of the earliest published reports, placing a very secretive Sidney Rigdon in the neighborhood of the Manchester Smiths prior to his first public visit with that same family at the end of 1830. If the "stranger" was Rigdon, it requires no great leap in logic to assume he also did some more "mysterious" visiting -- at Harmony in his home state of Pennslyvania, on May 15, 1829.

Tucker does not stop at recording vague memories of this "mysterious stranger," however: he speaks directly of Joseph Smith, Jr.'s 1829 baptism at Harmony and says that Joseph "went to Northern Pennsylvania, as previously appointed... and was baptized after the Mormon ritual -- Rigdon being the... officiating "clergyman" (Origin, p. 56). A few pages later, still speaking of Smith's baptism, Tucker says that Joseph "had previously received the ordinance in Pennsylvania by the ministration of 'Brother Rigdon,' and was the first Mormon baptized since the times of the primitive Nephites," (Origin, p. 60). So, in Tucker's 1867 work, we already have all the elements present for the identification of Sidney Rigdon as the "John the Baptist" who restored the Aaronic priesthood to Joseph and Oliver in 1829.

The continual popularization of Eber D. Howe's saucy comments and Tucker's alleged memorial musings is well illustrated in Hubert Howe Bancroft's History of Utah, 1540-1886, (San Francisco, 1889). On page 79), Bancroft quotes Howe in saying: "...we now have John the Baptist, in the person of Sidney Rigdon. Their plans of deception appear to have been more fully matured and developed after the meeting of Smith and Rigdon..." Bancroft directly follows this quotation with a mention of Tucker's comments concerning Sidney Rigdon's "messenger of God" activities in New York. These kinds of accusative references may be found scattered throughout the anti-Mormon literature of the 1880s and 1890s.

William A. Stanton and Smith's "Angel"

One notable proponent of the Rigdon=Angel claims from that period was the Rev. William A. Stanton, a writer

and a Baptist minister who lived in Pittsburgh. In an undated newspaper clipping, from an

June, 1899 Pittsburgh paper,

is found one of Rev. Stanton's sermons, entitled: "Rigdon as the Angel."

In this article Stanton says: "Smith claimed to have been directed by an angel to the burial place of a stone box in which was a volume

six inches thick and composed of thin gold leaves... My father-in-law, then 19 years old, lived near there, and is still living. He knew

Smith... just the man for Rigdon's use, although he proved in the long run too much for his master. It will probably never be known why

Rigdon had to take second place in Mormonism... In 1830 the book was printed, and with it a sworn statement by Cowdery, Harris and a

David Whitmer that an 'angel of God' had shown them the plates from which the book purported to be a translation. In after years these

three men renounced Mormonism and said that their sworn statement was false." Stanton is technically incorrect in saying that all three

of the Book of Mormon witnesses renounced their sworn statement, but he does assert that Rigdon was "the Angel" with a degree of

believability -- and shows absolutely no reliance upon Dr. Whitsitt's anti-Mormon writings. It is not difficult to imagine an anti-Mormon reader of Stanton's

sort of article, at the end of the 19th century, looking about for Cowdery's renuniation -- not finding it -- and then being tempted to fabricate that document himself.

Rev. Stanton wrote a similar article, entitled "The Relation of Sidney Rigdon to the Book of Mormon," which was published in the

July 22, 1899 issue of the Chicago Standard. There he says

much the same thing all over again, and adds these assertions: "during the summer of 1827 (the "Leaves of Gold" were found in September, 1827) a

stranger made several visits at Smith's home. He was afterward recognized as Rigdon, who afterward preached the first Mormon sermon at Palmyra....

In light of this evidence, whence think ye came the Book of Mormon, and what is its claim to divine authority? Was not Rigdon

Joseph Smith's angel?" Stanton's views on this subject were reprinted in Edgar E. Folk's 1900 book, The Mormon Monster, and

as the section headed: "Sidney Rigdon was Joseph Smith's 'Angel'" in Stanton's own 1907 book, Three

Important Movements, (Philadelphia: Am. Bap. Pub. Soc., pp. 36-41). Although

Stanton cites Whitsitt's book on the origin of the Campbellites, he is obviously unaware of the larger work from which that thin volume was excerpted

for publication -- Whitsitt's unpublished biography of Sidney Rigdon. Also, there is nothing in

any of Stanton's known writings to indicate that he picked up the Rigdon=Angel claim (or anything else regarding Rigdon) from Whitsitt's

1891 "Mormonism" essay -- most of Stanton's citations and ideas come out of Robert

Patterson, Jr.'s 1882 historical sketch on the origin of the Book of Mormon.

Mahaffey and Schroeder Add Their Views

The turn of the century seems to have been a particularly popular time for anti-Mormon writers to come out and say that Sidney Rigdon was Joseph Smith's angel. S. J. S. Davis, in his 1899 book, Origin of Book of Mormon implies a connection between Rigdon and Smith's angel; he says: "Rigdon... [obtained] Spalding's manuscript, and by some means placed it in the hands of Smith and Cowdery... how easy it was for Smith, who was already in communication with the celestial world, to have an angel direct him to the hill Cumorah." Rev James Ervin Mahaffey expanded upon this connection in writing his 1902 booklet, Found at Last: Positive Proof that Mormonism is a Fraud. On page 33 of this work Mahaffey says: "Now, according to Mormon theology, an angel is but an exalted man. They say, "God may use any beings he has made or that he pleases, and call them his angels or messengers." "God's angels and men are all one species, one race, one great family." "God is a man like unto yourselves; that is the great secret." YES, INDEED, THAT IS THE GREAT SECRET! Sidney Rigdon is an exalted man; therefore, Mormons may call him "God's angel or messenger."

Rev. Mahaffey derived some of this thinking on this point from the commendable work of A. Theodore Schroeder. In his 1901 book, The Origin of the Book of Mormon, Schroeder says: "I conclude... that the "Angel of the Prairies" who outlined to Pratt his then contemplated and now executed religious fraud, was none other than Sidney Rigdon himself, and that this fact accounts for Pratt's failure to give the name of his host or the date of his first meeting with Rigdon." Schroeder then goes on to give his opinion that Parley P. Pratt also carried out some equally deceptive angelic work in Rigdon's behalf, resulting eventually in the origin of Mormonism.

Schroeder's reporting was twice reprinted, many times cited, and eventually responded to in detail by the Mormon historian B. H. Roberts in 1908. All of this publicizing of the Rigdon=Angel explanation was going on during the opening years of the 20th century, at the very time when the spurious Cowdery Defence first surfaced. The RLDS Saints' Herald reprinted the document in its issue of Mar. 20, 1907, saying that it had "recently" come to the editor's attention. In fact, as the Tanners point out, the Rev. Robert B. Neal first published the pamphlet months earlier -- in about the middle of 1906. The fact that Rev. Neal mentioned the forged Cowdery text as early as "June 3, 1905," (as the Tanners also document) does not necessarily mean that Neal had any such publication in his hands at that time. In fact, in mentioning the alleged Cowdery "Defence" in the June-July, 1905 issue of The Helper, Rev. Neal clearly states that he only has an "excerpt" from the pamphlet -- implying that he was working from a handwritten transcription.

The Tanners infer that William H. Whitsitt probably wrote and/or published the spurious Cowdery pamphlet some time before June 3, 1905, and that Neal re-published Whitsitt's forgery the following year. Neal's publication was headed with the title: "Anti-Mormon Tracts, No. 9." If there was really a Whitsitt forgery, published prior to June 3, 1905, no known copies survive. Perhaps this fact convinced the Tanners that they had to include R. B. Neal as a knowing or unknowing participant in the forgery. Probably they were right in implicating Rev. Neal (the first known publisher of the bogus Cowdery text) in this sordid affair -- but not for the reason they imagined when they wrote their 1989 article.

R. B. Neal, Professional Anti-Mormon

Disciples of Christ minister, the Rev. Robert B. Neal (1847-1925) was a well-known anti-Mormon tract-writer and journalist. By 1897 (perhaps earlier) Neal was "holding forth" from Grayson, Kentucky, where he contributed an occasional journalistic attack upon the Mormons to local newspapers like the Carter County Bugle.

Not long after Rev. Neal began to attack the Mormons in the public press, a number of militants within the "Campbellite" movement came together to form the "National anti-Mormon Missionary Association of the Disciples of Christ." This group was formally organized at Omaha on Oct. 21, 1902 and its leadership included the notable former Latter Day Saint, Elder Davis H. Bays. Serving with Elder Bays on the new Association's Board of Directors was the Rev. Robert B. Neal. The cooperation between the ex-RLDS Bays and the zealous R. B. Neal reached back several years before the founding of this group, however. Rev. Neal took notice of Bays' "exposure" of the Saints as published in his 1897 book, The Doctrines and Dogmas of Mormonism. Encouraged by Bays' success in getting such a book into print, R. B. Neal set about researching and publishing his own anti-Mormon writings, beginning with his 1898 pamphlet, Was Joe Smith a Prophet? As may be seen in his earliest writings, Neal accepted the ex-RLDS missionary's views on most topics, but he did not go along with Bays' notion that Joseph Smith, Jr. wrote the Book of Mormon practically unassisted (Bays admitted some probable imput from Oliver Cowdery). The Mormons delighted in pointing to Rev. Bays' maverick opinions, as indicating doctrinal confusion among himself and his Campbellite brethren (see, for example, "Williams-Bays Debate" in the Aug. 18, 1898 issue of Zion's Ensign).

At the end of 1902 Rev. Neal became the editor of the official organ of the National anti-Mormon Missionary Association, the Helper, which he issued at Olive Hill (and later at Moorhead), just west of Grayson, in Carter Co., Kentucky. R. B. Neal's editorial article, "The Book of Mormon," published in the Aug. 1903 issue of the Helper, provides some insight into Neal's obsession with the idea that ex-Mormons like Oliver Cowdery must have denounced the religion and its "Bible of the Western Continent," (as Neal labels the 1830 book). His obsession with this probability took Neal on a quest to find the holy grail of anti-Mormonism, a denunciation of the religion as a fraud, from the lips of primary witnesses Martin Harris, David Wjitmer, or Oliver Cowdery. And, it is likely that it was Rev. Neal's publicized quest for such damning documentation that resulted in somebody writing the spurious Cowdery "Defence" early in 1905.

By Dec. 1904 the National anti-Mormon Missionary Association had added to its ranks the famous Mormon-eater, Clark Braden; he became a member of its Board of Management and R. B. Neal was made its General Secretary. The Helper for that month solicited financial contributions to further the group's "tract plans... to battle Mormonism." Rev. Neal switched into "high gear" and began to issue his anti-Mormon leaflets at about this same time (see various issues of the Disciples' Christian Standard from this period to view Neal's articles and some relevant reports on his activities). Neal merged his Helper periodical into the Disciples' Christian Weekly, but that paper soon folded. Around the beginning of 1907, the Disciples of Christ denomination apparently quit sponsoring the National anti-Mormon Missionary Association. Before long, that original organization deteriorated into what was pratically R. B. Neal's one man show, "The American Anti Mormon Association," of which Neal was the self-styled head.

Operating as the "American Anti-Mormon Association," out of Grayson, R. B. Neal published and distributed copies of his early "Anti-Mormon Tracts" and his new "Sword of Laban" leaflet series between 1905 and 1908. The last of his "Anti-Mormon Tracts" was his "No. 9," Oliver Cowdery's Defence and Renunciation, which he published in mid 1906.

It is perhaps important to note here that Rev. Neal published this particular tract right at the time when the Disciples of Christ were beginning to distance themselves from his anti-Mormon operations and right at the time he was seeking publicity and financial support to continue his endangered publishing efforts. As I mentioned already, his "official organ" of the National anti-Mormon Missionary Association, the Cincinnati Christian Weekly, ceased publication shortly after Neal issued his Cowdery "Defence" tract, and the "Association" went out of business not long thereafter. Although conclusive evidence is not yet available, I am tempted to think that Rev. Neal printed up his "Tract No. 9" as part of his last ditch effort to salvage and reinvigorate the dying National anti-Mormon Missionary Association.

R. B. Neal's "Cowdery" Tract #9

This was also about the first time that the spurious Oliver Overstreet "Confession" was first placed in circulation. On page 11 of their 1989 article, Jerald and Sandra Tanner say: "It is our belief that one of the major reasons that the Overstreet "Confession" was written was to destroy a statement concerning the Spalding-Rigdon theory of the origin of the Book of Mormon which was attributed to Oliver Cowdery when he returned to the church in 1848. According to the report in 'The Myth of the Manuscript Found,' p. 80, Oliver Cowdery proclaimed that the Book of Mormon 'is true. Sidney Rigdon did not write it. Mr. Spaulding did not write it.'"

The Tanners may be correct in their "belief" that the fabricated Cowdery Defence and the forged Overstreet Confession are in some way connected, but are they also correct in their saying "A number of things could make one suspicious that William Whitsitt had something to do with the Cowdery Defence and the Overstreet Confession?" It seems that the "one" who is dealing out these kinds of suspicions is actually the Tanner twosome. And, having painted Dr. Whitsitt as the probable secret author of the bogus Cowdery Defence, they also try to frame him as the counterfeiter of the spurious Overstreet document. What next? perhaps accuse him also of writing the "Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion?"

My own conclusion is that there is far more evidence linking the Rev. Robert B. Neal to these kinds of early 20th century forgeries than there is for pointing to Dr. Whitsitt's fancied participation in such nefarious schemes. But, having said that much, I might as well also reveal at this point that I do not believe that Rev. Neal personally wrote either the Cowdery Defence or the so-called Overstreet Confession. I will explain my thoughts on this important point by and by.

Untangling the "Neal Connection"

With the demise of the Disciples' National anti-Mormon Missionary Association, at the end of 1906, the Rev. Robert B. Neal put together a loose, inter-denominational coalition of anti-Mormons, under the banner of the American Anti-Mormon Association. Among the contributors to R. B. Neal's new anti-Mormon publishing efforts was the ex-RLDS writer, Charles A. Shook. Shook left the Reorganized Mormons in 1895 and became an ordained minister with the Advent Christian Church. In 1911 he became a member of the Disciples of Christ. After gaining some experience in the anti-Mormon business by writing for Rev. Neal, Shook undertook the writing of his own books: The True Origin of Mormon Polygamy and Cumorah Revisited, both printed near the end of 1910 and made available for sale at the beginning of 1911. The latter book was published by the Disciples of Christ's Standard Publishing Co., as was a 1914 reprint of the former volume. In 1914 Shook also induced the Standard Publishing Co., to print his third book, The True Origin of the Book of Mormon. This last volume was the first known work on Mormonism (other than R. B. Neal's publications) which reproduced (on pp. 50-54) Rev. Neal's 1906 Cowdery "Defence." The Rev. Neal must have been excited by the appearance of Shook's 1914 True Origin, for the Mar. 10, 1915 issue of the Saints Herald speaks of "Mr. Shook, whose work R. B. Neal says will 'shake the foundation' of Latter Day Saintism."

In the course of his anti-Mormon research and reporting, R. B. Neal gained access to some of the papers of Thomas Gregg (1808-1892), author of the 1890 book, The Prophet of Palmyra. Among that unpublished trove was a letter addressed to Gregg, written by Judge William Lang, and dated "Tiffin, O., Nov. 5, 1881." This document Neal first published (on pp. 12-14 of Tract #9) then made available to Shook, who reproduced it in his 1914 book, on the pages directly following his reprint of the spurious Cowdery "Defence." In his note on page 58, Shook says: "The letters of Lang, Gibson and Mrs. Bernard have been turned over to the American Anti-Mormon Association by the family of Th. Gregg, to whom they are addressed." Although Shook goes on to say that he took his text for the 1881 Lang letter "directly from the original," and although Judge Lang's son authenticated his father's handwriting in 1907, there is no way of knowing for certain that all of the pages of the 1881 letter in R. B. Neal's keeping, which Shook inspected, were truly Judge Lang's holographs. In fact, I think we must hold open the possibility that extraneous material may have been interpolated into Judge Lang's letter, by a later, anti-Mormon hand. The "suspect" text in this 1881 letter (as published) includes the following startling disclosure:

"What is claimed to be a translation is the 'Manuscript Found' worked over by C[owdery]. He was the best scholar amongst them. Rigdon got the original at the job printing office in Pittsburgh as I have stated. I often expressed my objection to the frequent repetition of 'And it came to pass' to Mr. Cowdery and said that a true scholar ought to have avoided that, which only provoked a gentle smile from C[owdery]. Without going into detail or disclosing a confided word, I say to you that I do know, as well as can now be known, that C[owdery]. revised the 'Manuscript' and Smith and Rigdon approved of it before it became the Book of Mormon."

Judge Lang wrote elsewhere about his close personal relationship with Oliver Cowdery (see, for example, his 1880 History of Seneca County, Ohio, p. 364), but he is not known to have anywhere else made a claim that Cowdery told him that the Book of Mormon was based upon Spalding's "Manuscript Found." What is the explanation for Lang's singular admission?

In their 2000 CD-ROM book, the authors of the Spalding Enigma call this same missive the "controversial letter written by Lang about Cowdery." On page 741 the Enigma authors reproduce (from James D. Bales' expanded reprint of Richard C. Evans' 1920 book), the same authentication from Judge Lang's son (dated May 30, 1907) that I previously mentioned. The contents of the son's letter appear to confirm that Judge Lang's testimony of 1881 was correctly published after his death -- but those same Enigma authors strongly suspect that somebody (R. B. Neal?) tampered with Judge Lang's holograph, inserting the damning confession of Oliver Cowdery into an original which never mentioned the incident. In private conversations with these authors they related to me their reasons for suspecting that R. B. Neal only sent Judge Lang's son a photograph of a portion of the 1881 letter, when he solicited the son's confirmation of the handwriting. They surmise the "original" held by R. B. Neal was a doctored document and the section relating Cowdery's confession, a spurious insertion. Unfortunately the original of Judge Lang's letter has long since disappeared from public view and is nolonger available for inspection and analysis.

While it is possible that the 1881 Lang letter did read as the Rev. R. B. Neal published the text, it also seems possible that the original may have been tampered with and that Rev. R. B. Neal may have known of this forgery, and yet chose to get the doctored document authenticted and published. At the very least, this possible fabrication of source material useful to the anti-Mormons should induce us to exercise some caution in accepting at face value the unique documents reproduced in Neal's and Shook's writings. Also, we should recall that it was R. B. Neal who first printed the fake Cowdery "Defence" and that the Tanners (whether right or wrong) feel that the unpublished Overstreet Confession is somehow linked to Neal's publication of that "Defence." All of this, I think, compels us examine critically any "lost" historical documents whose texts were first published by Rev. Neal.

Charles A. Shook's 1914 book contains yet another unusual item that the author apparently obtained from R. B. Neal. On page 120 Shook reprints a purported note penned by Dr. Cephas Dodd, on June 6, 1831, onto the fly-leaf of his personal copy of the 1830 Book of Mormon. Yet, on pages 1087-88 of their CD-ROM, the Enigma authors effectively demonstrate that the purported 1831 Dodd note is a forgery. After covering this matter they say: "Because the appearance of this supposed inscription roughly coincides with that of two other equally suspicious items, a document relating to Oliver Cowdery known as the "Overstreet Confession," and a pamphlet allegedly by Cowdery entitled "Defence in a Rehearsal of my Grounds for Separating Myself from the LDS," it does not seem unreasonable to speculate that this may have derived from the same source." In other words, the Enigma authors believe that the Rev. Robert B. Neal either forged or abetted the forgery of all of these "lost" documents and eventually provided them (along with a Lorenzo Saunders letter and other American Anti-Mormon Association "documents") to the unwary Charles A. Shook, as damning anti-Mormon "evidence" for his 1914 book. This being accepted as probable truth, the question remains unanswered: Did Rev. Neal perform the forgery, or did he simply pass along highly questionable documents to his readers without taking the trouble to verify their purported origins?

Dr. Daniel Braxton Turney

In order to begin to answer the question just posed, I will elucidate what appears to be a pattern of "lost" document publication activities by the Rev. Robert B. Neal, in which the name of one particular discoverer of "lost" documents recurs: that of Dr. Daniel B. Turney. The first implicit mention that Rev. Neal makes, concerning the discovery of the alleged 1839 Cowdery pamphlet, came in the comments he appended to an article titled, "Oliver Cowdery's Recantation," in the April-May 1905 issue of The Helper, where he says: "We have confirmatory evidence to hand out." His readers would have to wait for the next issue of The Helper, in July, 1905, to see exactly what the "confirmatory evidence" was that Neal here so cryptically refers to. The modern reader, skipping ahead to the June-July issue can there read the article "Oliver Cowdery and the Canada Revelation." containing an alleged excerpt from the words of Oliver Cowdery, as reportedly first published in his 1839 pamphlet.

In introducing the very first publication of alleged Cowdery excerpt, Rev. Neal says: "We are indebted to Bro. D. B. Turney, Goreville, Ill., for the following extract from 'Cowdery's Defence' made in 1839." The impression conveyed by this sentence is that Daniel B. Turney first sent Rev. Neal a handwritten "extract" of a single paragraph, which Turney purported to have copied from the only surviving copy of the 1839 pamphlet. Presumably Turney first informed Rev. Neal of this "rare find" during the spring of 1905; next sent him the handwritten excerpt; and finally provided Neal with the entire text -- but whether as a publication or a written transcript remains unknown.

Daniel B. Turney and Robert B. Neal

Dr. Daniel Braxton Turney (1848-1926) was a well educated Illinois politician and a clergyman-turned-polemicist in the Methodist Protestant Church. He was ordained in 1873 and in later years sometimes served as President of annual conferences of that church. Turney was a U. S. Presidential candidate for the "United Christians" in the campaigns of 1908 and 1912. He authored numerous articles and tracts on his own, and evidently supplied Rev. Neal with several unique and highly suspicious documents supposedly related to early Mormonism.

Rev. Neal first mentions Dr. Turney's name in the April-May 1905 issue of The Helper, the same number in which Neal alludes to having "confirmatory evidence to hand out" about Oliver Cowdery's abandonment of Mormonism. Actually, Turney bursts onto the anti-Mormon scene with a flourish, being described by Neal as a "prince among polemics," who is "anxious to enter the lists" in fighting the Latter Day Saint elders.

Dr. Turney's name again appears in the following issue of The Helper, where Rev. Neal credits him as being the supplier of the Cowdery "Defence" text.

However, when Neal reports and reproduces part of this same "document that is as rare as oranges in Greenland" in the July 8, 1905 issue of the Cincinnati Christian Standard, he neglects to specify exactly where and how he acquired the marvelous text. Also, in writing to Elder Wingfield Watson, on June 5, 1903, Rev. Neal says nothing about his source for the "Oliver Cowdery's Defence" which he had "just got" the previous day. Since Rev. Neal obviously wished to use the contents of this "Defence" to argue against Watson's affirmation of Mormonism, it seems strange that Neal did not better document the authenticity of the wondrous new discovery. I can only wonder if Turney requested Neal not to publicize his role in coming up with the Cowdery "Defence." Did D. B. Turney shy away from accepting the kind of national publicity by which he might have been called upon to display his alleged specimen of that otherwise unattested document?

Dr. Turney's next prominent mention in a R. B. Neal publication occurs in the Aug. 1908 issue of The Sword of Laban, where "D. B. Turney" of "Effingham, Ill." is listed as one of the Vice Presidents of Neal's new American Anti-Mormon Association. Two years later, in the Aug.-Sept. 1910 number, Turney supplies an article for The Sword of Laban, in which he says, "The testimony of the three witnesses may be studied in the light of hypnotism, or deliberate deception, or of collusion and fraud, or in the light of really not being their testimony." Turney does not indicate whether his transcript of the Cowdery "Defence" might be "studied" in the same "light." He does, however, say that "later testimony of the three witnesses, such as that issued by Oliver Cowdery in his "Defence," and by David Whitmer in his "Address," and by Martin Harris in his "Prophetic Letters," nullifies those witnesses' testimony to the divinity of the Book of Mormon. Whitmer's statements modify but do not invalidate his early testimony; Cowdery's "Defence" is a forgery; so, what about Harris' "Prophetic Letters?"

Here is what Dr. Turney says in that same article: "As these letters have not all seen the daylight of publicity, I take great pleasure in subjoining one of them which Mr. Harris sent to a friend of his..." At which point Turney inserts a Martin Harris letter, originally published by Eber D. Howe, in 1834. But there is an evident problem here: Turney quotes substantially more of the Harris letter than Howe printed, all of which is added in at the beginning of the text. Turney's addition to the Harris letter reads more like a modern writer's expansion of Howe's text than it does like the full, original document, from which Howe might have abridged his quotation. The part not in Howe's book appears to have some thematic affinities with those portions of the spurious "Cowdery Defence" in which Oliver is made to inadvertently reveal Mormon secrets in his faux, seemingly innocuous eye-witness reporting of the LDS past. Although there is no direct proof available to demonstrate that D. B. Turney doctored the old Harris letter, there appears to be literary evidence indicating that sort of textual tampering by somebody.

In 1910 R. B. Neal began publication of a short-lived paper called The Highlander. In the initial number of that periodical D. B. Turney has a short article, titled "A Stanza From a Nauvoo Hymn." Turney's quotation of the last four lines of the 1843 LDS "hymn" are highly suspect. They do not appear in the poem's original publication in the Times and Seasons, nor are they so quoted by any known source, other than Turney's undocumented assertion. It may not be coincidental that Dr. Turney supplied the only known text for the spurious 1839 "Cowdery Defence" -- another "lost" document available only from Turney and one in which the writer accuses Joseph Smith, Jr. of frequently predicting "that he himself shall tarry on the earth till Christ shall come in glory." This echoes the final, otherwise unattested, lines to Turney's version of the hymn: "And he [Smith] shall live to see Christ come... tarry in his fleshly home E'en till the judgment day."

Although Joseph Smith, Jr. apparently did state that Mormon Elders in the Kirtland School of the Prophets, would see Christ face to face, Smith is not known to have predicted his own "tarrying on the earth till Christ shall come." This 1839 (?) assertion from the Cowdery "Defence" is as suspect as is Turney's 1910 quotation of the Nauvoo hymn. Again, the method used in attacking the Mormons' faith in their old leaders is a laconic one -- Turney produces a hitherto unknown text, attributed to an early Mormon leader, which, when read at a much later date makes that leader sound like a liar, a dupe, or both. This is the effect of the otherwise unattested additional lines in the Harris letter; this is the effect of the otherwise unattested additional lines in Nauvoo hymn; and this is the effect of the otherwise unattested Cowdery confession -- all of which came through Dr. Turney and none of which has ever been produced as an original source document.

The 1831 Dodd Document and Related Matters

Two items remain to be examined by the cautious student of R. B. Neal publications: the bogus 1831 Cephas Dodd statement and the undated "Overstreet Confession." In the case of the first, otherwise unattested text (also never produced as an original source document), Rev. Neal does not attach Turney's name to its first publication in the Sept. 1908 issue of his Sword of Laban. In fact, Neal gives no source and no supporting evidence for the existence of the Dodd statement. Neal reproduces the dubious statement in the 12th issue of his Sword of Laban, but offers no explanation as to where it came from. The same text was reprinted by Charles A. Shook, in 1914, but Shook, too, fails to tell where, when and how this alleged fly-leaf testimony was obtained. On pages 1086-88 of their Spalding Enigma CD-ROM, the authors effectively demonstrate that the purported 1831 Dodd note is a forgery, probably made during the first years of the 20th century. In support of this conclusion they cite a letter written by Dr. Dodd to Col. Thomas Ringland, Mar. 2, 1857, in which Dodd says he has "no knowledge" on the assertion of Solomon Spalding having written the Book of Mormon, "which would be of any avail."

As I've already mentioned, the Enigma authors recently asserted: