RESEARCH AND INTERESTS OF THE LATE VERNAL HOLLEY

About Mr. Holley | Holley Library | "Josephus... BoM" (1981) | "BoM Authorship" (1992)

"Christianity... Pagan World" (1994) | "Christian Scripture" (1996) | "Zoroastrianism " (1997)

"Mormonism & Masonry" (1998) | "Swedenborg & BoM" (1999) | "The Great Secret" (2000)

Christ & Caesars (1879) (Eng) | Sayings of Jesus (1908) | True Authorship of N. T. (1979)

"Gospel of Thomas Pericopes" (1997) | Who Wrote NT? (1995) | Caesar's Messiah (2005)

|

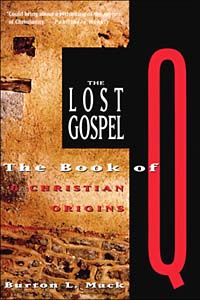

Burton L. Mack

The Lost Gospel (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1993) |

|

Copyright © 1993 by HarperCollins -- All rights reserved.

Only limited, "fair use" excerpts reproduced here.

|

[vii]

1 PROLOGUE: The Challenge 15 1. Finding the Shards 29 2. An Uncommon Wisdom 41 3. Removing the Patina 51 4. Galilee Before the War PART 2: The Text of the Lost Gospel 71 5. The Book of Q PART 3: The Recovery of a Social Experiment 105 6. Dancing to the Pipes 131 7. Singing a Dirge 149 8. Claiming a Place 171 9. Coming to Terms PART 4: The Reconception of Christian Origins 191 10. Jesus and Authority 207 11. Mythmaking and the Christ 227 12. Bishops and the Bible 237 13. Christians and Their Myth 259 Appendix A: Early Christian Literature 260 Appendix B: Q Segments 263 Select Bibliography 269 Index

[viii]

|

Copyright © 1993 by HarperCollins -- All rights reserved.

Only limited, "fair use" excerpts reproduced here.

Copyright © 1993 by HarperCollins -- All rights reserved.

Only limited, "fair use" excerpts reproduced here.

Copyright © 1993 by HarperCollins -- All rights reserved.

Only limited, "fair use" excerpts reproduced here.

Copyright © 1993 by HarperCollins -- All rights reserved.

Only limited, "fair use" excerpts reproduced here.

Copyright © 1993 by HarperCollins -- All rights reserved.

Only limited, "fair use" excerpts reproduced here.

Copyright © 1993 by HarperCollins -- All rights reserved.

Only limited, "fair use" excerpts reproduced here.

Copyright © 1993 by HarperCollins -- All rights reserved.

Only limited, "fair use" excerpts reproduced here.

Copyright © 1993 by HarperCollins -- All rights reserved.

Only limited, "fair use" excerpts reproduced here.

|

[ 103 ] P A R T I I I THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT

[ 104 ]

[ 105 ]

6 Dancing to the Pipes Q is packed with bright, memorable sayings. Some are pithy aphorisms, such as "Don't judge and you won't be judged." Others ride on picturesque images like gathering figs from a thornbush or what happens to tasteless salt. Exhortations that recommend striking behavior abound, as in the injunction to offer the other cheek when slapped. Succinctly phrased observations on the everyday world collide with clever conclusions about the wily ways of human pursuits. Anecdotes, parables, colorful condensations of epic lore, and pointed apocalyptic pronouncements fill the horizon of an imaginative world that stands to challenge the status quo. Q bristles with critical judgments on truths held to be self-evident and social conventions that most people would have taken for granted. Q1's challenge to its readers was to have another look at their world and dare to dance to a different tune. However, sorting through these sayings to find the reasons for such talk is a difficult exercise. At first one has the impression of a motley collection of ad hoc material put together in a helter-skelter fashion. One hardly knows what to make of it as a whole. The older theory about Q1's composition was based on this impression. It held that these sayings traveled separately in oral tradition, that each saying was considered an important pronouncement in its own right, and that each was added to various collections made at different times for the purpose of convenience and the preservation of sayings held to be 106 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT sacred because Jesus had said them. Compositional design was therefore not to be expected. This theory still has some value, for it recognizes that Q was re-worked at several stages in a community that collected and cultivated these sayings over a long period. Many of the sayings seem out of place, appearing to reflect different periods in the life of the community. Some sayings suggest a very early period in the community's life ("Don't worry, you are worth more than the birds"), while others deal with issues and questions that could only have arisen later ("Rejoice when they reproach you; that is exactly how they treated the prophets"). And some sayings appear to have been added to the collection in order to address the situation of the community in the period after the Jewish war ("Jerusalem, Jerusalem, your house is left desolate"). But as soon as one sees that the sayings cluster and that clustering shows signs of purpose, a closer analysis is necessary. Recent studies have shown that it is possible to be quite precise about the reasons for the clusters and their arrangement in the larger collection. One can see blocks of material organized by theme, sayings that illustrate or comment upon others, and small units of what the Greeks would have called a complete argumentation. Frequently, the way sayings are grouped or ordered makes a point. Sometimes a saying offers a specific interpretation of a preceding unit of material, or draws a conclusion that redirects the significance of a theme and points to the next cluster. If one pays careful attention to shifts in features such as grammar, tenor, formal characteristics, and implied audience, strategies can be discerned that indicate compositional design rather than simple aggregation. Discrete stages in the literary history of such a collection are much more difficult to identify. That is because, in the nature of the case, rearrangements in the order of proverbial material frequently raise the design of previous collections. And, since it is always the arrangement of proverbial material that provides the literary context for interpreting a particular figure of speech, earlier connotations are easily lost. A breakthrough occurred when it was seen that seven clusters of sayings in Q share distinctive features that are missing in the rest of the material. Some of these clusters are carefully composed rhetorical units, and all of them address a coherent set of issues with the same

DANCING TO THE PIPES 107

audience in view and the same concerns in mind. When analyzed, these compositions do not need the rest of Q in order to make sense as a set of instructions. Further study established that the scribes responsible for Q as a whole had reason not to entirely erase the design of this earlier collection. That fortuitous accident of scribal history, retaining earlier instructional material that happened to be in the form of small compositions, makes it possible to isolate an earlier layer of tradition in Q and thus an earlier stage in the history of the Q community. These seven clusters are now recognized as the remains of the earliest collection of sayings in the Q tradition, the layer of Q material called Q1. They are precious nuggets indeed. A thorough account of the scholarly excavation of these foundation stones is hardly possible, for the labor has been painstaking and the arguments intricate. But we need to understand the reasons scholars have marshalled for being so sure about the assignment of these clusters to the early layer of the Q tradition. Some of these reasoris have to do with the identification of "seams," places where it is obvious that sayings were added or joined to others when elaborating or expanding upon themes. In order to be certain about seams, a mastery of Greek syntax is required, but even in English translation thematic shifts are easily seen, and careful attention to the sequence of material will often reveal the logic of primary and secondary considerations in the development of themes and the conjunction of blocks or units of speech. An example is the reference to Sodom in QS 21, a saying that picks up on the immediately preceding Q1 saying about an unreceptive town and shifts to the Q2 theme of judgment on Galilean towns elaborated in the sayings that follow. Identifying seams where material was added to prior material is a standard procedure in the study of sayings collections and instructional handbooks of antiquity. Seams tell us that collections were frequently changed in the process of transmission by means of notations, additions, deletions, and the reorganization of material. Sayings collections, called gnomologia (from gnome, meaning "maxim"), were not considered sacred literature that should be left intact and passed on just as it had been received. A second set of reasons has to do with the coherence of a given layer of material in the development of a tradition. Reading through the document as a whole, different types of material that share similar 108 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT (this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions)

DANCING TO THE PIPES 109

reconstruct the earliest period of the Q movement. The seven clusters assigned to Q1 are the following: QS 08 ON THOSE WHO ARE FORTUNATE QS 09 ON RESPONDING TO REPROACH QS 10 ON MAKING JUDGMENTS QS 11 ON TEACHERS AND STUDENTS QS 12 ON HYPOCRISY QS 13 ON INTEGRITY QS 14 ON PRACTICAL OBEDIENCE 2. Instructions for the Jesus Movement QS 19 ON BECOMING A FOLLOWER OF JESUS QS 20 ON WORKING FOR THE KINGDOM OF GOD 3. Confidence in the Father's Care QS 26 HOW TO PRAY QS 27 CONFIDENCE IN ASKING 4. On Anxiety and Speaking Out QS 35 ON SPEAKING OUT QS 36 ON FEAR 5. On Personal Goods QS 38 FOOLISH POSSESSIONS QS 39 ON FOOD AND CLOTHING QS 40 ON HEAVENLY TREASURE 6. Parables of the Kingdom QS 46 THE MUSTARD AND THE YEAST 7. The True Followers of Jesus QS 50 ON HUMILITY QS 51 THE GREAT SUPPER QS 52 ON THE COST OF BEING A DISCIPLE QS 53 SAVORLESS SALT Embedded in these blocks of Q1 material are a number of terse sayings that give the collection its distinctive tone. An example is the saying in QS 39 that "life is more than food." Every smaller unit of composition has at least one terse saying. Some are formulated as maxims, others as imperatives, but all have the quality of aphoristic 110 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT speech. Most of these aphorisms function within their units as core sayings around which the unit clusters, or on which supporting considerations build. When viewed together, moreover, these sayings make a comprehensive set of sage observations and unorthodox instructions. They delight in critical comment upon the everyday world and they recommend unconventional behavior. These sayings put us in touch with the earliest stage of the Jesus movement when aphoristic discourse was the norm. I shall refer to this period in the social history of the movement as stage 1. The blocks of material in Q1 build upon this aphoristic core by adding arguments to confirm its insights and by developing rules for living creatively in the light of its critical assessment of the everyday world. I shall refer to the social experience reflected in the blocks of Q1 material as stage 2. To catch the flavor of discourse from the pre-Q1 period of the Jesus movement (stage 1), it will help to list the following aphorisms (paraphrased in some cases in order to highlight the point and encourage a fresh look): Everybody embraces their kin. (QS 09) The standard you use will be the standard used against you. (QS 10) Can the blind lead the blind? (QS 11) A student is not better than his teacher. (QS 11) A good tree does not bear rotten fruit. (QS 13) Foxes have dens, birds have nests, but humans have no home. (QS 19) The harvest is abundant, the workers few. (QS 20) Everyone who asks receives. (QS 27) Nothing is secret that will not be revealed. (QS 35) People are worth much more than the birds. (QS 36) Life is more than food. (QS 39) The body is more than clothing. (QS 39) Where your treasure, there your heart. (QS 40) Everyone who glorifies himself will be humbled. (QS 50) Whoever tries to protect his life will lose it. (QS 52) If salt is saltless, it is good for nothing. (QS 53)

DANCING TO THE PIPES 111

(this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions) 112 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT assessment is a better guide than status, and that life would be more rewarding if lived another way. In general it is clear that sympathies lie with the poor, the least, the humble, the servant, and those consigned to positions without privilege, more than with their social opposites. But more than this cannot be said without additional information. The aphoristic sayings just cited are phrased as maxims, which means they counted as statements that were considered generally true of the social world in view. If one now looks for aphoristic sayings that are phrased as imperatives, not maxims, a somewhat clearer picture of the better way to live begins to emerge. Instructions actually predominate in Q1, and most of the blocks of Q1 material are composed in support of instructions set forth as imperatives. Many of these imperatives are succinctly phrased and are aphoristic in character. Some of them appear to turn the observations in the maxims around and recommend a mode of behavior appropriate to the critical stance. This means that the better way of life was actually enjoined as livable. If we look for aphoristic imperatives that function as core pronouncements or clearly illustrate the theme in a cluster of Q1 sayings, the following sayings emerge (using paraphrase again to make the point): Love your enemies. (QS 09) Bless those who curse you. (QS 09) If struck on one cheek, offer the other. (QS 09) Give to everyone who begs. (QS 09) Judge not and you won't be judged. (QS 10) First remove the stick from your eye. (QS 12) Leave the dead to bury their dead. (QS 19) Go out as lambs among wolves. (QS 20) Carry no money, bag, or sandals. (QS 20) Greet no one on the road. (QS 20) Eat what is set before you. (QS 20)

DANCING TO THE PIPES 113

Don't be afraid. (QS 36) Don't worry about your life. (QS 39) Make sure of God's rule over you. (QS 39) Sell your possessions and give to charity. (QS 40) One wonders at the crisp formulations of such a curious challenge. The forthright imperatives evince a sense of seriousness, but why one should take them seriously is not expressly stated. In order to understand their attraction and significance we need a fuller picture of the way of life that is being recommended. If we expand the data base somewhat, by noting the way in which these core aphorisms are elaborated in the larger blocks of Q1, a number of themes surface for repeated emphasis. The list includes such items as the following: Lending without expectation of return (QS 9) Critique of riches (QS 8, QS 38, QS 40) Etiquette for begging (QS 9, QS 27) Etiquette for troublesome encounters in public (QS 20) Nonretaliation (QS 9, QS 10, QS 20) 114 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT Severance of family ties (QS 19, QS 52) Renunciation of needs (QS 8, QS 19, QS 39, QS 40) Call for authenticity (QS 13, QS 35, QS 53) Critique of hypocrisy (QS 12) Fearless and carefree attitude (QS 36, QS 39) Confidence in God's care (QS 26, QS 27) Sense of vocation (QS 19, QS 20) Discipleship without pretension (QS 11, QS 14, QS 38, QS 50, QS 52) Singlemindedness in the pursuit of God's kingdom (QS 19, QS 39, QS 40, QS 52, QS 53) New Testament scholars have often remarked on the Cynic parallels to much of the material in Q1. Since such similarity often comes as a surprise to Christian readers of the gospels, accustomed as they are to hearing the words of Jesus against the background of the prophetic speech of the Hebrew scriptures, few have concluded that the Cynic analogy should be taken seriously. A Cynic look-alike Jesus would, in any case, present something of an embarrassment due to the fact that the Cynics are remembered mostly for their unlovable ways. The modern caricature of the ancient Cynics usually calls to mind the unsavory figure of Diogenes of Sinope and dwells upon his habits of biting sarcasm and public obscenities. To be cynical in modern parlance is also fraught with negative connotation. Cynicism is equated with disengaged negativity, giving up rather than confronting the challenges of life. To be cynical is never thought to be helpful when questions about the meaning of life are seriously under review. The modern caricature of the ancient Cynics is inaccurate and the modern use of the word cynic to describe the ancient Cynics is unfair. A more,balanced view would see the Cynics as the Greek analogue to the Hebrew prophets. Cynics played a very important social

DANCING TO THE PIPES 115

role as critics of conventional values and oppressive forms of governance for approximately one thousand years, from the fifth century, B.C.E. to the sixth century C.E. Their popular philosophy produced such figures as Antisthenes, Diogenes, Crates, Bion, Teles, Meleager, Musonius Rufus, Dio Chrysostomos, Demonax, Peregrinus Proteus, Sostratus, and Theagenes -- all important figures in the history of Greek thought. Their gifts and graces ranged from the endurance of a life of renunciation in full public view, through the courage to offer social critique in high places (called parresia, or "boldness of speech") to the learning and sophistication required for the espousal of Cynic views at the highest level of literary composition. Justly famous as irritants to those who lived by the system and enjoyed the blessings of privilege, prosperity, and power, the Cynics were highly regarded for their achievement in honing the virtue of self-sufficiency (autarcheia in the midst of uncertain times. Epictetus' third discourse is a remark able revelation of a Stoic's high esteem for the Cynic's calling as an important social role even during the imagined halcyon age of the Roman imperium. The crisp sayings of Jesus in Q1 show that his followers thought of him as a Cynic-like sage. Cynics were known for begging, voluntary poverty, renunciation of needs, severance of family ties, fearless and carefree attitudes, and troublesome public behavior. Standard themes in Cynic discourse included a critique of riches, pretension, and hypocrisy, just as in Q1. The Cynic style of speech was distinctly aphoristic, as is that in Q1. And Cynics were schooled in such topics as handling reproach, nonretaliation, and authenticity in following their vocation, matters at the forefront of Jesus' instructions in Q1. If Jest was remembered as a Cynic-like sage, we need to make sure we understand why the Cynics behaved as they did. The public image was that of the lone beggar who had renounced the comforts of life to pit himself against the elements and practice the virtues of living with little. The Cynic wore a telltale cloak and carried a pouch for the day's morsels and the morrow's coins. A stick and sandals were also allowed, but that was all. A favorite form of anecdote called chreia, used these props to characterize the Cynic's resolve, depict him in the most destitute of straits, and explore the wit required to live with hunger, cold, and public reproach. Thus, when one of his students complained of the cold, Antisthenes told him to fold his cloak 116 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT double. When a child used his hands to get a drink of water, Diogenes threw his cup away and said that a child had bested him in the contest for living simply. When someone slapped him in reproach, Diogenes asked himself out loud why he had forgotten to wear his helmet that day. We have hundreds of anecdotes that follow this form. The ancient Greeks got their point and delighted in their cleverness. These popular philosophers of a natural way of life did not wander off to suffer in silence. Their props were a setup for a little game of gotcha with the citizens of the town. Those who dared to give the Cynic any attention at all usually found themselves in contradiction. It mattered little whether a bystander or a passerby was generous or abusive. A scurrilous remark could be turned to advantage by exposing the underlying cultural taboo as ridiculous. An offer to help would also receive a put-down by triggering some remark about those who have and those who do not. Either way, the Cynic's purpose was to point out the disparities sustained by the social system and refuse to let the system put him in his place. According to one story, bystanders had commended a person for giving Diogenes a handout, whereupon he said, "Have you no praise for the one who was worthy to receive such a gift?" Thus the marketplace was the Cynic's platform, the place to display a living example of freedom from social and cultural constraints, and a place from which to address townspeople about the current state of affairs. As might be expected, the Cynic was a favorite target for ridicule. That, of course, was just what the Cynic wanted. Public performance and close encounter with the barefaced straights was exactly what the Cynic vocation called for. The Cynic response often seemed harsh and aggressive, but to make his point there was always a touch of humor as well. The challenge for a Cynic was to see the humor in a situation and quickly turn it to advantage. A large number of Cynic anecdotes feature this ability. Some examples are the following stories about Diogenes of Sinope recorded by Diogenes Laertius in his Lives of Eminent Philosophers. When told that people were laughing at him, Diogenes said, "But I am not laughed down." When asked why he was begging from a statue, he said, "To get practice in being refused."

DANCING TO THE PIPES 117

When asked what kind of wine he preferred, he replied, "The kind another pays for." When someone said that life was bad, he replied, "Not life itself, but living as you do." In our time there is no single social role with which to compare the ancient Cynics. But we do recognize the social critic and take for granted a number of ways in which social and cultural critique are expressed. These compare nicely with various aspects of the Cynic's profession. For example, we are accustomed to the social critique of political cartoonists, stand-up comedians, and especially of satire in the genre of the cabaret. All of these use humor to make their point. We are also accustomed to social critique in a more serious and philosophical vein, such as that represented by political commentary. And there is precedent for taking up an alternative life-style as social protest, from the utopian movement of the nineteenth century, to the counterculture movement of the 1960s, to the environmentalist protest of the 1980s and 1990s. The list could be greatly expanded, for much modern entertainment also sets its scenes against the backdrop of the unexamined taboos and prejudices prevailing in our time. Each of these approaches to a critical assessment of our society (satire, commentary, and alternative life-style), bears some resemblance to the profession of the Cynic sage in late antiquity. Those who study the Cynic's wit soon discover that humor was more than an adornment to their game. Gotcha had rules, and the rules demanded that the Cynic see and take advantage of the humor in a situation. To play the game and win, the Cynic would have to accept a reproach by letting it stand as a statement that was true, a description of his behavior with which he would have to agree. "Well, you are right. I did do that. I did say that." But then, by a series of rapid mental gymnastics, the Cynic would (1) seize on some feature of his opponent's statement that revealed an assumption with which the Cynic did not agree, (2) shift to another way of looking at the situation (or to a different set of circumstances in which the statement would not apply), and (3) come up with a retort that exposed the challenger's statement as a naive cliche. A fine example of this strategy is found in the story about Diogenes who, when reproached for entering unclean places (probably 118 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT a euphemism for a house of prostitution), said, "But the sun enters the privies without being defiled." The retort lets the statement of his challenger stand but shifts attention to a case in which "entrance" into an "unclean" place does not result in becoming unclean. For a moment the confusion of categories strikes one as funny. It also creates a sense of uncertainty about the assumptions underlying the challenger's reproach. In the anecdotes cited earlier, the critical twists from challenge to response shift in idiom (laughing at/laughing down), purpose (begging to get/begging as an exercise), classification (kinds of things/ kinds of human exchange), and quality (life in general/a certain lifestyle). The lack of fit when applying a common taboo to an inappropriate situation, or the gap between a challenge and the Cynic's response, creates humor. But the humor covers a devastating, if momentary, insight into the partiality of conventional perceptions and thereby offers a critical perspective on their underlying logic. Noting the Cynic's wit should not divert our attention from their sense of vocation and purpose. Epictetus wrote that the Cynic could be likened to a spy or scout from another world or kingdom, whose assignment was to observe human behavior and render a judgment upon it. The Cynic could also be likened to a physician sent to diagnose and heal a society's ills. If asked for his credentials, the Cynic might well claim to be a messenger sent by the gods. Epictetus, at least, had no hesitation in finding such language fully appropriate, although for a Greek such a reference to divine vocation could easily be made without creating mystique or claiming supernatural status. Thus there was method in the Cynics' madness. In fact, leading Cynics were often regarded as philosophers, and Cynicism was frequently accorded rank among the schools of Greek philosophy. The Stoics sometimes claimed the Cynics as their precursors in order to trace their own school of thought back to Socrates. But everyone knew that Cynic intellectuals did not organize schools in the grand tradition and were not impressed with abstract conceptual systems put forth to explain an ordered universe. They were much more interested in the question of virtue (arete), or how an individual should live given the failure of social and political systems to support what they called a natural way of life. They borrowed freely from any and every popular ethical philosophy, such as that of the Stoics, to get a

DANCING TO THE PIPES 119

certain point across. That point was the cost to one's intelligence and integrity if one blindly followed social convention and accepted its customary rationalizations. Cynics had no trouble appealing to the intelligence of the people. They trusted the capacity of the average person to see through the rhetoric of common discourse and assess a human situation at its grubby level of personal desire and manipulation. Their task was not to pose as teachers of truths people did not know, but to challenge people to live in accordance with what they did know. They constantly called attention to the accidental nature of social status and the ephemeral rewards of material success. They criticized social structures of hierarchy, domination, and inequity by poking fun at the superficial codes of honor and shame that supported them. They took every opportunity to deflate the egos of the privileged. And they delighted in exposing the ulterior motive of calculated action. What counted most, they said, was a sense of personal worth and integrity. One should not allow others to determine one's worth on the scale of social position. One already possessed all the resources one needed to live sanely and well by virtue of being a human being. Why not be true to the way in which the world actually impinges upon you? Say what you want and what you mean. Respond to a situation as you see it in truth, not as the usual proprieties dictate. Do not let the world squeeze you into its mold. Speak up and act out. Verve was therefore the Cynic virtue. It was generated by a sense of self-reliance, but involved the capacity for taking a lively interest in any and every encounter with another human being. Verve could also be used as a standard to diagnose human well-being, rank human achievement, and assess the merits of social systems and their cultural symbols. Nevertheless, the Cynic critique of cultural conventions finally came to rest, not on society as a system, but on the shoulders of the individual who was willing to live "according to nature." The invitation was to take courage and swim against the social currents that threatened to overwhelm and silence a person's sense of verve. Such a philosophy was custom-made for Galilean circumstance during the late hellenistic period. The age-old Galilean strategies for accommodating foreign rulers would have been hard pressed under the accelerated shifts in governance that were taking place. Shrugs with respect to the loyalties demanded by foreign kings, priests, and 120 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT (this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions)

DANCING TO THE PIPES 121

(this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions) 122 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT considered a complete argumentation. Analogies were usually taken from the natural order, while examples were taken from life. If a complete argumentation was well done, it was thought to be persuasive. QS 39 is a complete argument on the thesis that one should not worry: Reason: Life is more than food and the body is more than clothing. Analogy: Ravens do not work for food; God provides for them. You are worth more than birds. Example: No one can add a day to life by worrying. Analogy: Lilies do not work, yet are clothed. Example: Solomon in all his splendor was not as magnificent as the lilies. Analogy: Notice the grass. If God puts beautiful clothes on the grass, won't he put clothes on you? Conclusion: One should not worry about food and drink. Example: All the nations worry about such things. Exhortation: Instead, make sure of God's rule over you, and all these things will be yours as well. Every block of Q1 material exhibits the same strategy: QS 8 moves from the aphoristic "How fortunate the poor" to a tripartite characterization of the Jesus people (the poor, the hungry, and those with reason to mourn), and finally to a blessing on those who suffer

DANCING TO THE PIPES 123

(this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions) 124 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT How fortunate the poor; theirs is God's kingdom. (QS 8) No one who puts his hand to the plow and then looks back is fit for God's kingdom. (QS 19) If you enter a town and they welcome you, eat what is set before you, attend to the sick, and say that "God's kingdom has come near to you." (QS 20) But if you enter a town and they do not welcome you... say, "Nevertheless, be sure of this, that God's rule has come to you." (QS 20) When you pray, say, "Father.... may your kingdom take place, give us each day our daily bread." (QS 26) Make sure of his rule over you, and these things will be yours as well. (QS 39) What is God's kingdom like? It is like a grain of mustard.... It is like yeast which a woman hid in three measures of flour. (QS 46)

DANCING TO THE PIPES 125

(this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions) 126 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT (part of this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions) Stoics internalized the image of the king and idealized the individual who ruled his passions and controlled his attitudes even in circumstances where others governed his existence. Their strategy was to be hopeful about the constructive influence of such individuals on society. A popular Stoic maxim was "The only true king is the wise man." Cynics were not as sanguine about the philosopher's chance of influencing social reform, but they also used the royal metaphor to advantage. In their case, taking control of one's life required extrication from the social scene. They lived "according to nature," they said, and the natural order was imagined as a realm of divine rule in opposition to the prevailing social order. As Epictetus put it, the Cynic's staff was his "scepter," his mission was to represent the great king Zeus, and the Cynic's "sovereignty" was the imperious bearing with which he "ruled" in the public arena by telling and showing others how they should live. The use of the term kingdom of God in Q1 matches its use in the traditions of popular philosophy, especially in the Cynic tradition of

DANCING TO THE PIPES 127

performing social diagnostics in public by means of countercultural behavior. The aphoristic imperatives recommended a stance toward life in the world that could become the basis for an alternative community ethos and ethic among those willing to consider an alternative social vision. Thus the spread of connotation must be kept in mind when encountering the term God's kingdom in Q. The language of the kingdom of God in Q captures precisely the ambiguities involved in the range of connotation from ruling as behavior to rule as domain: from individual to group, behavior to ethos, practice to conceptual order, human society to divine order. The thought had not yet occurred at the Q1 level, as it did later at the Q2 stage, that the location of God's kingdom was to be found precisely in the social formation of the movement. But it is clear that an overlap had already occurred between the concept of the rule of God as an alternative realm or way of life everywhere available to daring individuals, on the one hand, and the ethos of the movement as the particular manifestation of God's kingdom on the other. That is why the language of the rule of God in Q1 refers not only to the challenge of risky living without expectation that the social world will change but also to the exemplification of a way of life that like-minded persons might want to share. The God in question is not identified in terms of any ethnic or cultural tradition. This fits nicely with Galilean provenance, and since the metaphors of God's rule are largely taken from the realm of nature, the conception of God in Q1 is also compatible with the Cynic tone of the teachings. The match between the Cynics and the Q people is not exact, however, mainly because the Cynics had no interest in emphasizing the divine aspect of either the natural order or the rule they represented. The people of Q, on the other hand, did emphasize that the rule they represented was the rule of God. There is little more to be learned about the nature of this God from the sayings about his kingdom, but other sayings about God in Q1 (paraphrased below) represent him as a father: 128 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT Father... give us... pardon us... do not bring us to trial. (QS 26) If you who are not good know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will the father in heaven give good things to those who ask him. (QS 27) If God puts beautiful clothes on the grass... won't he put clothes on you...? Your father knows that you need these things. (QS 39) In Q1 the embryonic social formation of the movement has to be inferred from the nature of the discourse. In Q2, on the other hand, a vivid picture of the Jesus movement comes into view as a fully self-conscious movement. Before we move to that stage of the group's history, however, there is one more important window into the early period of socialization that Q1 provides, and this is the instruction about working for God's kingdom in QS 20. This instruction contains the saying about being sent out as lambs among wolves, a formulation that retains its Cynic flavor and is best understood as an address to individuals. However, it also contains a saying about a large harvest with few workers, a saying that implies some kind of program. And appended to the harvest saying is the injunction to beg the master of the harvest to send out laborers. Recent studies of this instruction have argued convincingly that of these two sayings, the one about the lambs and wolves is the earlier. This means that the developmental sequence discernible in Q1 as a whole is also true of this instructional

DANCING TO THE PIPES 129

(this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions) 130 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT (part of this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions) It is clear that these instructions were formulated as guidance for a movement that had spread throughout Galilee, and that Jesus people who were not personal acquaintances might be found in other towns. Spreading would have taken place in the normal course of contact and travel wherever talk about God's rule caught the attention of persons willing to listen. Apparently, many were quite attracted to the Jesus people and their talk about the rule of God. Their diagnosis of the social situation must have made sense and their challenge to risk reproach by taking in hand what one could of one's own life must have sounded right. But as groups formed in different places and the teachings of Jesus became the topic of conversation, recognition of kindred spirits became an issue, and the arena of activity shifted from the public sphere to the house group. The earlier Cynic-like life-style, geared as it was for a critical encounter with the world, would have become inappropriate. What it meant to live in accordance with the rule of God would now have to be worked out in relation to persons and problems within the group. Thus the codification of Cynic-like injunctions as community rules in Q1 can be understood as a response to the problems of social formation. As we shall see, these problems surface in Q2 as the primary cause for a marked shift in both the discourse and the life-style of the Jesus movement. |

Copyright © 1993 by HarperCollins -- All rights reserved.

Only limited, "fair use" excerpts reproduced here.

|

[ 131 ]

7 Singing a Dirge A sudden shift in tone awaits the reader of Q2. The new temperament is so strongly profiled that a comparison with the sayings in Q1 is unavoidable and the contrast in mood overwhelming. It is a shift for which one has not been prepared, and the effect is stunning. The aphoristic style of Q1 falls away almost to the point of disappearing. Aphoristic imperatives are gone, as is the sense of confidence in God's care derived from the way in which nature provides for basic needs. In its place one hears the voice of a prophet pronouncing judgment on a recalcitrant world, a prophet who does not refrain from castigation and the sledge of apocalyptic threat. The shift in tone is matched by a panoply of new forms of speech. In contrast to Q1 the reader now encounters narratives, dialogue, controversy stories, examples taken from epic tradition, descriptive parables, warnings, and apocalyptic announcements. If one looks for corresponding changes in the rhetoric and style of discourse one is not disappointed. Instead of exhortation ("Don't worry"), there is pronouncement ("The last will be first, and the first will be last"). Instead of imperatives ("Love your enemies"), there is direct statement ("I came to strike fire on the earth"). Indirect address ("Who then is the faithful servant") is interspersed with direct address ("You must be ready"). Formulas of reciprocity, such as "The standard you use is the standard used against you," are tightened and shift their setting of consequence from what happens in the public sphere to what 132 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT will happen in the kingdom of God. And all of these judgments and verdicts are rendered with an authority that does not brook appeal. New ideas also are encountered. The expanded horizon introduces figures from the epic tradition. A man named John enters the picture. There is reference to the wisdom of God and the holy spirit. There are two miracle stories and warnings about what to say when put on trial. The rule of God is now spoken of as a kingdom to be fully revealed at some other place and time, presumably at the end of time. And a final judgment is described replete with thrones, court scenes, banishments, and a threatening figure called the son of man. A listing of the major blocks of material in Q2 illustrates the shift that took place and the constant presence of the theme of judgment. QS 03 THE APPEARANCE OF JOHN QS 04 JOHN'S ADDRESS TO THE PEOPLE QS 05 JOHN'S PREDICTION OF SOMEONE TO COME 2. What John and Jesus Thought About Each Other QS 15 THE OCCASION QS 16 JOHN'S INQUIRY QS 17 WHAT JESUS SAID ABOUT JOHN QS 18 WHAT JESUS SAID ABOUT THIS GENERATION 3. Pronouncements Against Towns That Reject the Movement QS 21 THE UNRECEPTIVE TOWN QS 22 THE GALILEAN TOWNS 4. Congratulations to Those Who Accept the Movement QS 23 ON THE ONE WHO RECEIVES THE WORKER QS 25 ON THE ONE WHO HEARS AND SEES 5. Controversy with This Generation QS 28 ON KINGDOMS IN CONFLICT 6. Making Sure Whose Side You Are On QS 29 THOSE FOR AND THOSE AGAINST QS 30 THE RETURN OF AN EVIL SPIRIT 7. Judgment on This Generation QS 32 THE SIGN OF JONAH

SINGING A DIRGE 133

QS 33 THE LAMP AND THE EYE 9. Pronouncements Against the Pharisees QS 34 O YOU PHARISEES 10. On Anxiety and Speaking Out QS 37 ON PUBLIC CONFESSIONS 11. The Coming Judgment QS 41 THE HOUR QS 42 ON FAITHFULNESS QS 43 FIRE AND DIVISION QS 44 SIGNS OF THE TIMES QS 45 SETTLING ACCOUNTS 12. The Two Ways QS 47 THE NARROW GATE AND CLOSED DOOR QS 48 EXCLUSION FROM THE KINGDOM 13. Community Rules QS 54 WHEN TO REJOICE QS 55 EITHER/OR QS 57 ON SCANDALS QS 58 ON FORGIVENESS QS 59 ON FAITH 14. The Final Judgment QS 60 THE DAY OF SEPARATION QS 61 SQUARING ACCOUNTS The theme of judgment is very closely related to an apocalyptic imagination. The threat of coming up short in a final judgment flows like an undercurrent from the preaching of John to the parable of the talents. Many of the prophetic pronouncements, images of destruction, and the parables of exclusion take their seriousness from this apocalyptic backdrop even when it is not made explicit. It is also the apocalyptic framework that forced a reconception of God and made it possible to imagine the rule of God as a realm to be fully revealed only at the end of time. The inverse is also true, however, and this is an important point to understand. The apocalyptic imagination is very closely related to 134 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT (this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions)

SINGING A DIRGE 135

(this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions) 136 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT (this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions)

SINGING A DIRGE 137

(this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions) 138 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT (this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions)

SINGING A DIRGE 139

(this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions) 140 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT (this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions)

SINGING A DIRGE 141

(this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions) 142 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT (this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions)

SINGING A DIRGE 143

(this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions) 144 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT (this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions)

SINGING A DIRGE 145

(this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions) 146 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT (this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions)

SINGING A DIRGE 147

(this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions)

[ 148 ]

|

Copyright © 1993 by HarperCollins -- All rights reserved.

Only limited, "fair use" excerpts reproduced here.

Copyright © 1993 by HarperCollins -- All rights reserved.

Only limited, "fair use" excerpts reproduced here.

|

[ 171 ]

9 Coming to Terms The Roman-Jewish war brought to an end a glorious epoch in Jewish history and created consternation for Jews and Jesus people alike. The war lasted the better part of ten years, from the riots and skirmishes of 66 C.E., through the battles that raged around and within Jerusalem for four years, to the fall of Masada in 73 C.E. Reading the history of the war written by Josephus, one gets the impression that the internecine conflicts within Judea and Jerusalem were as devastating to the social order as the armies of the Romans were to the city walls and defenses. When it was over, the temple was in ruins, Jerusalem was a burned wasteland, and many of the people of Judea had been uprooted and scattered throughout Palestine, Transjordan, and the cities along the coast. It was a bloody end to the second temple-state, and there was no official leadership left to put its pieces back together. There were, as a matter of fact, hardly any pieces left. What to think and do was the question. None of the many forms of Jewish society was unaffected by this event. The Jewish aristocracy, the priests, the Pharisees, the village councils, the scribes attached to the network of stations, the Qumran enclave, and the local leaders of diaspora synagogues had to rethink what it meant to be a Jew and how to reorganize Jewish society. Samaritans and Galileans had also been embroiled in the upheaval, caught in the middle between the Jerusalem establishment and the Romans. Erstwhile loyalties were hardly the only issue as the armies 172 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT came and went. Whose side to be on was a practical question that wrenched every family, village, and town. Everyone was unsettled by the confusion and violence of the times. And the Jesus movements also had to find some way to weather the storm. Q3 provides a little window into the Q community after the war. It is too small a window to see as much of the social landscape as one would like, and it provides only hints of what it must have been like for the people of Q during the war. During that period of their history there was apparently little time for reflection or occasion for coming to agreements on attitudes and strategies appropriate for the movement. But some of the people of Q did manage to stay in touch with one another, and Q3 provides us with evidence that the movement survived. It also reveals that three or four shifts in attitude occurred in the period after the war, and these point to a particular path that the Q people had decided to take. In this chapter we shall look through that window. It is our last chance to catch a glimpse of the Jesus people according to Q, for the Q3 additions were the last embellishments on the document of which we can be certain before it was subsumed by the authors of the narrative gospels later in the century. It is, of course, possible that Q continued to be copied and consulted by Jesus people who resisted the attractions of the new myths created by the narrative gospels, and that they went their own way. It is also conceivable that the Q3 edition was not the last change to the document within that kind of group, and that Q continued to have its own illustrious history of revision independent of the use made of it by the authors of the narrative gospels. But if so, history passed those people by, for there are no records of a Jesus movement using only a document like Q after the narrative gospels appeared. What we do know is that the community of Q produced a very popular document that was widely read during the last quarter of the first century. It must have been copied many times and shared among several groups of Jesus people who were going separate ways. Mark, Matthew, and Luke each used a copy of Q independent of each other, and each made use of Q from a distinctly different perspective. So Q was still in circulation as a document at the end of the first century. But what that might say for the history of the Q community is very difficult to assess. The text of Q had been dislodged from the group

COMING TO TERMS 173

that produced it; the period was one of vigorous social and intellectual experimentation within the Jesus movement; and the people of Q certainly were capable of shifting perspectives and entertaining new ideas. If one were to ask which of the narrative gospels most nearly represents an ethos toward which the community of Q may have tended, it would be the Gospel of Matthew. But to see that connection should not foreclose on other turns that may have been taken. Unfortunately, after Q3 we simply lose track of the Jesus people who produced the document called Q. What we can do is trace four fateful turns in the history of the Q document before it also slips from sight. Three of these junctures in its literary history are the ways in which it was used by each of the authors of the narrative gospels. The fourth has to do with its relation to the Gospel of Thomas. What happened to Q in relation to these other gospels needs to be kept in mind as we turn to the matter of revising the conventional picture of Christian origins in part IV of this book. (part of this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions) 174 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT (this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions)

COMING TO TERMS 175

(this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions) 176 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT The third and truly surprising novelty in Q3 is an attitude that the people of Q took with regard to the authority of the Jewish scriptures and the relevance of the written law. In the temptation story Jesus is pictured in debate with the accuser over the requirements of the law. In the saying on hearing and keeping the teaching of God the reference appears to be to the scriptures (QS 31). The charges against the Pharisees are effectively retracted by the Q3 addition that the codes on washings, alms, and offerings are to be kept (QS 34). And in the segment of sayings on the law, the written law stands even if heaven and earth were to pass away (QS 56). There is even a saying to the effect that remarriage after divorce counts as adultery (QS 56). It thus appears that the people of Q made some adjustments in their self-understanding. The period of conflict with "this generation" was past. The debate over the Pharisaic standards of piety was no longer wrenching. The community was still committed to its claim to represent the kingdom of God, but it was now aware of its own dislocation from the social and political landscape of its times. A retreat from social conflict to care for its own ethical integrity had apparently found the words of Jesus insufficient as a guide. Having already used the scriptures for the purpose of laying claim to the epic tradition of Israel, they were now reconsidered as ethical guidelines appropriate to the kingdom of God. The function of the scriptures as an epic with etiological focus on Jerusalem was a thing of the past; the scriptures' were now available for reappropriation. Thus a Jewish sensibility won out as the community settled in for the long run. This move toward an accommodation of Jewish sensibility, reflected in the last layer of compositional history, is a most remarkable feature of Q. Although such a move seems surprising in light of the earlier history of the Q people, it must have been an appealing solution to the confusion created by the destruction of Jerusalem. It is, at any rate, the earliest evidence for an accommodation of the Jewish law within the Jesus movement, an accommodation that, when we meet it again in the Gospel of Matthew, can be called Jewish-Christianity. Jewish-Christianity became a very popular, widespread, influential, and long-lived legacy of the Jesus movements. The community of Q had not yet become a Christian community of this kind, however, and a move to accommodate Jewish law was not the only option taken by the followers of Jesus.

COMING TO TERMS 177

We must set the history of the Q community in the context of other groups of Jesus people who took different paths, experienced different social histories and group formations, and worked out different mythological rationales. The Christ cult, for instance, can only be understood as a Jesus movement that spread at an early period to northern Syria and Asia Minor where it quickly developed into a religious society on the model of a hellenistic mystery cult. The author of the Gospel of Mark was at home within some Jesus movement that had spread to the cities of southern Syria and tried, without success, to work out a common understanding with the local diaspora synagogues. To write his gospel, Mark used written traditions from yet another Jesus group that had experimented with a myth of origin in the genre of miracle story. And the Gospel of Thomas shows that a group very much like the people of Q, and perhaps a part of the Q movement during its very earliest phase, refused to get involved with the Q mission and then struck off on its own when the people of Q ran into opposition and began to call down judgments on "this generation." So the people of Q were only one configuration within a variety of groups that formed among the followers of Jesus. But the people of Q must have established one of the stronger traditions, because the document they produced came to be regarded by others as a very strong text. Strong texts attract strong readers, and strong readings intentionally subvert the original meaning of a text in the interest of creating a new vision by composing a new text. In the case of Q we have clear evidence of three very strong readings of the complete text (Mark, Matthew, and Luke) and one very strong reading of a sizable selection of the sayings in Q (the Gospel of Thomas). Q was the most important text in the hands of Mark, Matthew, and Luke as they composed their narrative gospels. Without Q they would not have been able to write the stories they did. And the Gospel of Thomas stands in the tradition of Q, subverting the original intention of its sayings in the interest of creating an entirely different ethos. A brief sketch of the way in which each of these authors purposely misread Q will be a fitting conclusion to the story of the lost gospel. Mark wrote his story of Jesus some time after the war and shortly after Q had been revised with the Q3 additions. If we date Q3 around 75 C.E. to give some time for the additions obviously prompted 178 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT by the war, Mark can be dated between 75 and 80 C.E. Mark's community also had been confused by the war, but it drew a conclusion about the war's meaning that was quite different from the position taken by the people of Q. Mark thought that the destruction of the temple was exactly what the Jews deserved. He based this partially on an old Jewish idea that had been used to account for other disasters and was alive once more, namely that the failure of their leaders to respond correctly to God's intention for them had occasioned his wrath and resulted in the destruction of the temple. But also, Mark thought they deserved it because the Jewish synagogues with which his group had been in contact had rejected the Jesus movement. This forced his group to reconsider their identity apart from this link to Israel's heritage. He therefore wrote his story of Jesus to give the impression that all of the Jewish leaders had rejected Jesus and thus sealed the fate of second- temple Judaism. To show this he told the story of Jesus' crucifixion as if it were a plot on the part of the Jewish leaders to get rid of Jesus because he had challenged their religion, law, and institutional authority. He was able to get by with this because the Jerusalem establishment and temple were no longer in existence. He achieved this fiction by combining (1) a few traditions from the Christ cult, such as its view of Jesus' death as a martyrdom and its practice of a memorial meal; (2) material from several Jesus movements other than Q, such as the stories in which Jesus debated with his opponents, called pronouncement stories, and two sets of miracle stories; and (3) the material that comprised Q. For Mark, Q was extremely useful, for it had already positioned Jesus at the hinge of an epic-apocalyptic history, and it contained themes and narrative material that could easily be turned into a more eventful depiction of Jesus' public appearance. Q provided Mark with a large number of themes essential to his narrative. He was taken with the epic-apocalyptic mythology, the theme of prophetic prediction, and the announcement of judgment upon the scribes, Pharisees, and "this generation." The figure of the son of man intrigued him, as did the notion that the kingdom of God would be fully revealed only at the eschaton when the son of man (or Jesus, according to Mark) (re)appeared. Q also provided material that could easily be turned to advantage as building blocks in a coherent narrative account.

COMING TO TERMS 179

The John-Jesus material was a great opener. The figure of the holy spirit was ready-made to connect the Q material on John and Jesus with the miracle stories Mark would use. Q1's characterization of Jesus as the all- knowing one could be used to enhance his authority as a self-referential speaker in the pronouncement stories Mark already had from his own community. The notion of Jesus as the son of God could be used to create mystique, divide the house on the question of Jesus' true identity, and develop narrative anticipation, the device scholars call Mark's "messianic secret." The instructions for the workers in the harvest could be turned into a mission charge, and the theme of discipleship could be combined and given narrative profile by introducing a few disciples into the story. The apocalyptic predictions at the end of Q could then become instructions to the disciples at that point in the story where Jesus turns to go to Jerusalem. And, as scholars know, there are a myriad of interesting points at which the so-called overlaps between Mark and Q show Mark's use of Q material for his own narrative designs. Naturally, Mark had to recast everything. An obvious switch is that Mark radically changed the Q material on John and Jesus. He pictured John as knowing his role as the predicted precursor for Jesus, invented a story about John actually baptizing Jesus, and used that scene to introduce Jesus to the reader and the world as the son of God endowed with the holy spirit. A very dramatic beginning. The temptation story would not work as Q had it, but it could be used in a truncated reference to make the transition from the Jordan to Galilee and dramatize Jesus' entrance there. The conflict with the scribes and Pharisees required a narrative setting and so would take place, according to Mark, in synagogues. And the mission that failed had to be revised. This turned out to be the hard part. To match Mark's plot, Jesus' appearance in Galilee had to be a public event in the grand style. It had to make sense as an occasion both for a successful mission and for a disturbance of sufficient gravity to launch the plot to have Jesus killed. Mark worked it out by dividing the populace into four groups. One was the people who were eager for Jesus' teachings and healings; in this sense the mission was a success. A second group, the Jewish leaders, understood enough to agree among themselves that Jesus had to be destroyed but not enough to accept his role as the king-to-be; in this sense the mission 180 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT was a failure. A third group, the disciples, were given instructions about the future kingdom of God, but were too dense to get it straight; so in this sense the mission was one of failed instruction. Who then were the ones who knew for certain what was happening? According to Mark it was the fourth group, the demons, but they were forbidden to tell. What a story. One can see why Mark left out most of the Q1 instructions. There was no place in his story for Jesus to be instructing people in the ethics of a Jesus movement. And besides, it was the mythological Jesus that had to be killed in order for the story to work as a myth of origin for Mark's rejected community because that is the way Jesus had come to be imagined. Any other Jesus would not have been their Jesus. And as for storytelling, it was one thing to cast Jesus as a sovereign figure whose challenge to the authorities resulted in his crucifixion, but it would have been an even greater problem to have imagined the Jewish leaders killing him because of his Q1 teachings. A plot against the teacher of Q material would have been even more horrific than the plot Mark devised against the son of God. So he could not use the Q material as the public instructions of a teacher who wanted to be understood. The overlaps that do occur between Mark and the instructional sayings in Q are interpreted mainly as Jesus' private instructions to the disciples. These include the sayings on things hidden and revealed, the lamp, the grain of mustard, the measure, savorless salt, taking up one's cross, and the formula of reciprocity on confessing or denying Jesus. Mark was highly selective in his use of Q material and he knew what he was doing. He had no intention of writing a story to grace and highlight the teachings of Q. He wanted to write a story that put the test to Jesus, not at the beginning as was befitting for a sage, but at the end as was befitting for a martyr for the kingdom of God. He did it. Now there were two strong texts among the Jesus people: Q and the gospel that Mark wrote. With both Q and Mark in circulation, we are now poised to see what Matthew and Luke made of them. In the meantime, however, yet another group of Jesus people had decided to pronounce a plague on both of these houses. The followers of Jesus responsible for the Gospel of Thomas had grown accustomed to the idea of Jesus as a sage and had given a great deal of thought to his teachings. For them, the significance of his teachings lay in their capacity to enable an individual to withstand society's

COMING TO TERMS 181

pressures to conform. They had meditated deeply on his sayings and taken seriously the challenge to disassociate from society and develop self-awareness, self-confidence, and self-sufficiency. When the Q people formed groups, started their mission, and then retreated behind a smokescreen of apocalyptic pronouncements when their mission failed, the Thomas people decided to go their own way. When Mark's community tried to imagine itself as a determining factor in the course of human history, the Thomas people thought that the legacy of Jesus had been betrayed. The Coptic Gospel of Thomas was a translation from a Greek original that scholars now date to the last quarter of the first century. It contains a truly amazing collection of the sayings of Jesus. When compared with Q, approximately one-third of the sayings in the Gospel of Thomas have parallels in Q, and about 60 percent are from the Q1 layer. This shows that the Thomas tradition had roots in the earliest stages of the Jesus movement and that there must have been some association with the Q people during that period. From that point on, however, the Thomas tradition is marked by a strong sense of independence. Three features of the text reveal just how independent the Thomas people were. The first noteworthy feature of the text is the use of dialogue in order to present the sayings of Jesus as answers to a number of questions his disciples ask. The reference to his disciples is, for the most part, collective. But Peter, Matthew, and James are mentioned, as are Thomas, Salome, and Mary. Thomas, Salome, and Mary say the right things, ask the right questions, and so are privileged to be part of an inner circle, as is James who is spoken of in his absence. These figures obviously represent the true followers of Jesus and thus reflect the Thomas group in the text. But Peter, Matthew, and "the disciples" usually ask the wrong questions and repeatedly and brusquely have to be corrected. Thus the dialogue format works both ways. It allows Jesus to instruct the inner circle in the true meaning of his teachings while also allowing the other disciples to represent views the Thomas people have rejected as wrong. A look at these other views is most instructive. The questions that Jesus consistently rejects as gross misunderstandings of what he represents can easily be classified in two categories. One is that concerns about the future are all misplaced. Over 182 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT and over again the disciples ask when the kingdom will come, how it will be, and whether they will be able to enter. In every case Jesus tells them that they have completely misunderstood his teachings about the kingdom. The kingdom, Jesus explains, is already present, and if they knew who they were, namely the true disciples of Jesus, they would know not to ask. The other set of questions has to do with ritual behavior. The disciples want to know whether and how they should fast, pray, give to charity, wash, diet, and whether circumcision is required. In every case Jesus treats their questions as silly, but takes the occasion to turn the ritual reference into a metaphor of the contemplative self-awareness characteristic for his true disciples. Thus the ruse of dialogue is used to clarify the position of the Thomas people on two fronts: Jesus people who became apocalyptic, and Jesus people who worked out an accommodation with the Pharisaic codes of ritual purity. Neither the Markan community nor the people of Q would have measured up as the true disciples of Jesus according to the Gospel of Thomas. The second noteworthy feature of the Gospel of Thomas is the content of the teachings that have no parallel in Q. All of them are what might be called second-level elaborations on those sayings that do have a parallel in Q. In Q the compositional history reveals identifiable strata. This is not the case with Thomas. But just as there was a shift in Q from aphoristic instruction to prophetic and apocalyptic discourse, so there was a shift in the Thomas tradition from aphoristic injunctions to another distinctive style of instruction. Highly metaphoric and largely enigmatic, the teachings of Jesus to his disciples tell them that true knowledge is self-knowledge, and that true self-knowledge is a state of being untouched by the world of human affairs, a state of being in touch with a noetic world of divine light and stability. In relation to the world of human affairs Jesus' true disciples are to "become passersby" (Saying 42). As those who know themselves they are the "solitary ones" (Saying 49). As those in touch with the noetic world they are "from the light" (Saying 50), "sons of the living Father" (Saying 50), those who "stand at the beginning and know the end" (Saying 18), who encompass male and female in "a single one" (Saying 22), who "know the kingdom" (Saying 46), and who are "the same" (Saying 61). Jesus refers to himself as the "light from above"

COMING TO TERMS 183

(Saying 77) who represents all that the disciples are to become. Once they see it, however, they won't need Jesus anymore: "Whoever drinks from my mouth shall become as I am and I myself will become he, and the hidden things shall be revealed to him" (Saying 108). It is this level of elaboration that qualifies the Gospel of Thomas as a proto-Gnostic treatise. The mythology is that of the incarnation of wisdom in the midst of a dark and senseless world. From the options available in Q and Mark, the Thomas people rejected the mythology of the apocalyptic son of man and the notion of the prophets as the envoys of wisdom or as those who predicted Jesus. They took, instead, the mythology of Jesus as the child of wisdom and son of God, detached it from its epic-apocalyptic frame, and cultivated his teachings as signatures of his self-knowledge as the incarnation of divine wisdom. The third feature of the text is the riddle-like feature of the sayings. According to the introduction, "These are the secret words which the living Jesus spoke and Didymos Judas Thomas wrote. And he said: 'Whoever finds the explanation of these words will not taste death" (Saying 1). With such an introduction, the author compounds the mysterious quality of the already enigmatic sayings. Not only are these secret sayings in the private property of the Thomas people, but when one gets to read them one finds riddles in need of the correct answers. So the text was written as a revelation document available to and understandable only by those who were privileged to be included in the Thomas community. As such a text makes apparent, the Thomas disciples were living in an imaginary world far removed from the people of Q or the Markan community. Their response to the troubled times was one of detachment. "Whoever finds himself," they heard Jesus saying, "of him the world is not worthy" (Saying 111). About this time (ca 85-90 C.E.), Matthew found a way to put Mark and Q together in a single account. Matthew's sympathies were with Q and it is quite possible that he belonged to a community in the tradition of Q. If so, the people of Q had continued to work on their problem of self-identification, for Matthew represents several solutions to issues still unresolved for the people of Q at the Q3 stage. It would also mean, as difficult as this is to imagine, that Matthew's branch of the people of Q had taken note of the Gospel of Mark and found it interesting. Matthew, In any case, did find Mark acceptable 184 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT (this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions)

COMING TO TERMS 185

(this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions) 186 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT (this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions)

COMING TO TERMS 187

(this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions) 188 THE RECOVERY OF A SOCIAL EXPERIMENT man who "went about doing good" because the spirit of God was upon him. So Luke incorporated Q into his gospel, but he was not overly interested in using its contents as instruction applicable in his own day. He treated Q as a period piece, one resource among many for the historian interested in developing a picture of Jesus, the prophet-teacher. This is why Luke did not fuss with Q as did Matthew, either by systematically rearranging the sayings by theme, or by making sure that the reader got the full import of the teachings of Jesus as Christian law. Luke saw the connections between Q and Mark in the stories about John and Jesus, and so took that part of Q and merged it with Mark at the appropriate place. He also followed the Q sequence by inserting the first block of Q1 material into the story as the "sermon on the plain" before introducing the dialogue between John and Jesus. But from that point on, Luke turned Mark's march toward Jerusalem into a long and leisurely journey during which Jesus walked and talked with his disciples, sent them on their mission and received their reports, had dinner with a Pharisee, performed a few healings, instructed the crowds, received a group of Galileans, and so forth. And Q was simply interspersed as the instructions Jesus gave on the way. The historian's sense of distance put Q in its place, albeit as a historian's fiction. The reader was no longer addressed directly, as in Q, by a voice speaking with immediate authority. Neither was the reader addressed indirectly, as in Matthew, by a founder-teacher laying down the law for all time. In Luke's account, the reader is allowed to imagine Jesus talking to those of Jesus' own time. It was a glorious time, but it was past and the times had changed. The importance of the teachings of Jesus for Luke was not their relevance for all time, but the record they left of a marvelous teacher and prophet whose effectiveness was only that he enlarged the congregation of the people of God to include gentiles. Thus the church was born. The irony is noteworthy. Luke's treatment of Q as a document not worth saving as a handbook of instructions relevant for his own time was the very feature of his composition that made its recovery possible in modern times. |

Copyright © 1993 by HarperCollins -- All rights reserved.

Only limited, "fair use" excerpts reproduced here.

|

[ 189 ] P A R T I V THE RECONCEPTION OF CHRISTIAN ORIGINS

[ 190 ]

[ 191 ]

10 Jesus and Authority The discovery of Q has forced a revision of the history of Christian beginnings. It has also demanded a shift in the way we understand early Christian mythmaking. Q documents a Jesus movement that produced a myth of origin simply by adding new sayings to a growing collection of the instructions of a founder-teacher. Such a mode of mythmaking has been difficult for modern scholars to accept. Early Christian myths of origin have usually been classified as kerygmatic or narrative. Q has expanded the options and thus invites a special consideration. What we need to understand is the process by which sayings continued to be ascribed to Jesus long after he lived. The traditional criteria for determining the "authentic" words of the historical Jesus are no longer valid. The question must now focus on the "inauthentic" teachings. New Testament scholars know that Jesus could not have said everything ascribed to him in the vast literature produced during the first three or four centuries. A recent collection of the sayings of Jesus from early Christian literature numbers 503 items (Crossan, 1986). Of these, less than 10 percent are considered candidates for authenticity by scholars working on this question. The traditional quest for the authentic words of Jesus focused primarily on the criteria for determining which sayings are authentic. Sayings that occur in gnostic treatises, or in the popular literature traditionally called pseudepigraphical, or "falsely written and signed," have easily been set aside. No critical scholar thinks that Jesus said, 192 THE RECONCEPTION OF CHRISTIAN ORIGINS "Cleave wood, I am there; lift a stone, you will find me there," as found in the Gospel of Thomas (Saying 77). No one doubts that the author of the gnostic treatise called Pistis Sophia invented Jesus' instructions to his disciples about the fall, repentance, and salvation of Pistis Sophia: "And the time came that she should be saved from the chaos and brought forth from all the darkness.... And the [first] mystery sent me a great light- power from the height, so that I should help the Pistis Sophia and bring her up from the chaos" (Pistis Sophia I, 60). And there is absolute embarrassment about the words of the child Jesus found in the infancy gospels. When slapped on the face by another child, for instance, Jesus, the six-year-old, told him to "finish his course," so that he died forthwith (Infancy Gospel of Thomas 5:1). The sayings that occur in the canonical gospels are a bit more tricky. Scholars have no trouble thinking that the words of Jesus in the Gospel of John were invented in the course of the community's meditations. Sayings such as "I am the living bread which came down from heaven; if anyone eats of this bread, he will live for ever" or "He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life" are simply dismissed as "Johannine." But the sayings ascribed to Jesus in the synoptic gospels have proven to be very difficult to assign. That is because New Testament scholars have assumed the image of Jesus created by the narrative gospels and thus have found it hard to discount self-referential sayings that in any other mouth would be found highly inappropriate. The criteria for judging authenticity have all been forms of a single persuasion, namely, that since Jesus was a unique individual, his teachings must have been novel. The difference between the sayings of Jesus and what others might have said has therefore been the major consideration for determining authenticity. A saying with parallels from Jewish or Greek traditions of proverbs and maxims would therefore be discounted. Sayings that address the theological or ethical concerns of the emerging "church" have likewise been considered inauthentic. Studies based on such criteria have not been without value, for they have situated many of the teachings of Jesus in appropriate traditions of discourse and demonstrated the inauthenticity of the majority of sayings ascribed to Jesus. But the short lists of "authentic" words that result from such an endeavor lack coherence, fail to enhance the picture of Jesus scholars have had in mind, and do

JESUS AND AUTHORITY 193

nothing to help explain the practice of ascribing the sayings to Jesus that scholars have called inauthentic. Meanwhile, consternation reigns outside of scholarly circles when people are told that Jesus did not say what Mark or Matthew or Luke said he said. Such consternation has been documented time after time in letters to the editors of newspapers in response to the published judgments of the Jesus Seminar. This group of New Testament scholars has been at work for several years preparing "the scholars' red letter edition" of the gospels (Funk, 1992), with the aim of summing up the best judgments of critical scholars in the quest for the authentic teachings of Jesus. Preliminary results of the voting with red, pink, gray, and black beads have regularly been published in the media. And then indignation is expressed by Christians who have always imagined that Jesus said what the scholars now say he did not. (part of this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions) 194 THE RECONCEPTION OF CHRISTIAN ORIGINS (this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions)

JESUS AND AUTHORITY 195

(this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions) 196 THE RECONCEPTION OF CHRISTIAN ORIGINS (this page not reproduced, due to copyright restrictions)

JESUS AND AUTHORITY 197